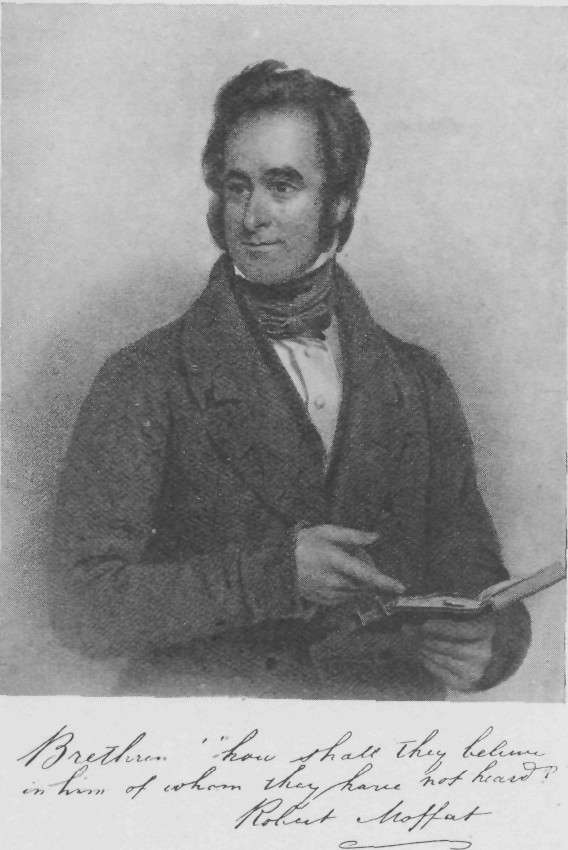

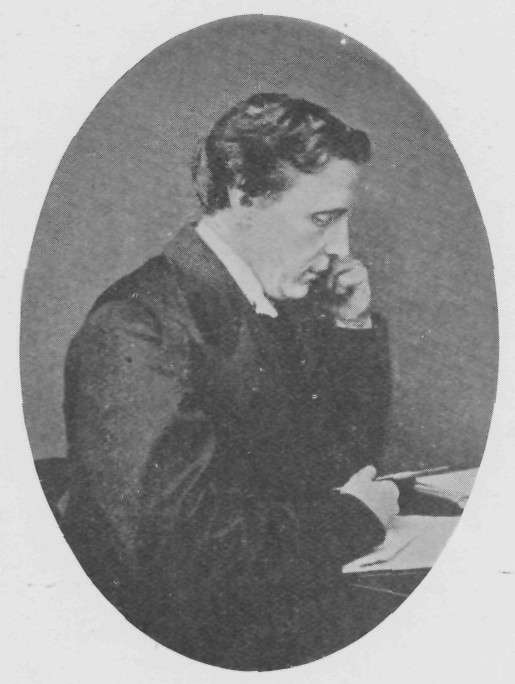

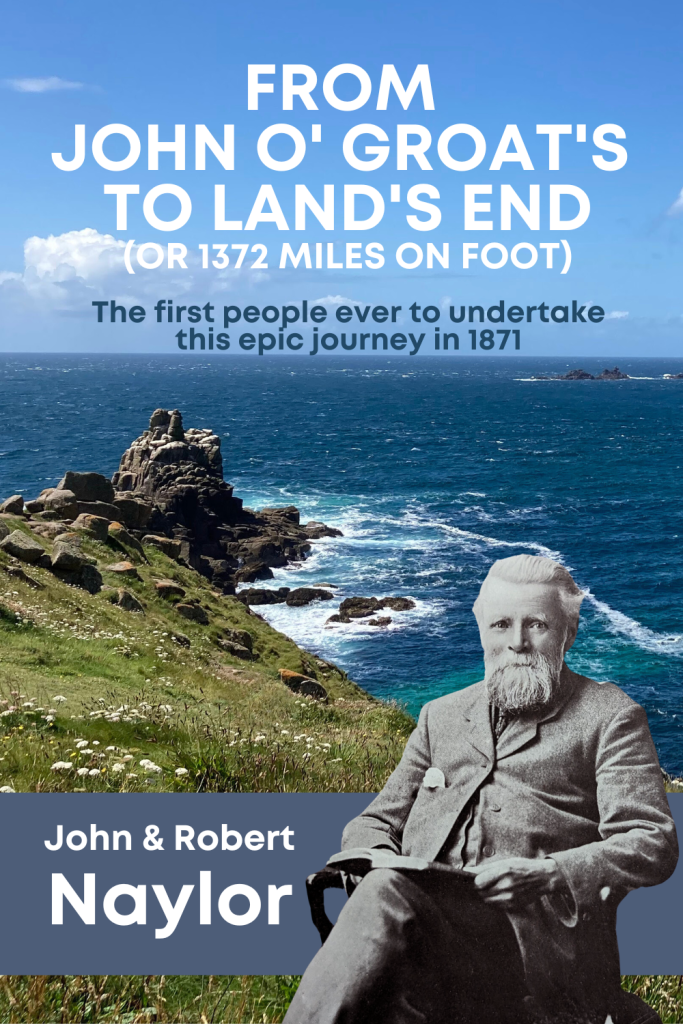

FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) My Great Great Grandfather, John Naylor and his brother Robert where the first people to walk from From John O Groat’s to Lands End in 1871. Read the book in full for free here on http://www.nearlyuphill.co.uk in chapters or download their 660 page book here – FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) All words are written by them and all pictures are taken from the original book which was written in 1916 by John Naylor.

SEVENTH WEEK’S JOURNEY — Oct. 30 to Nov. 5.

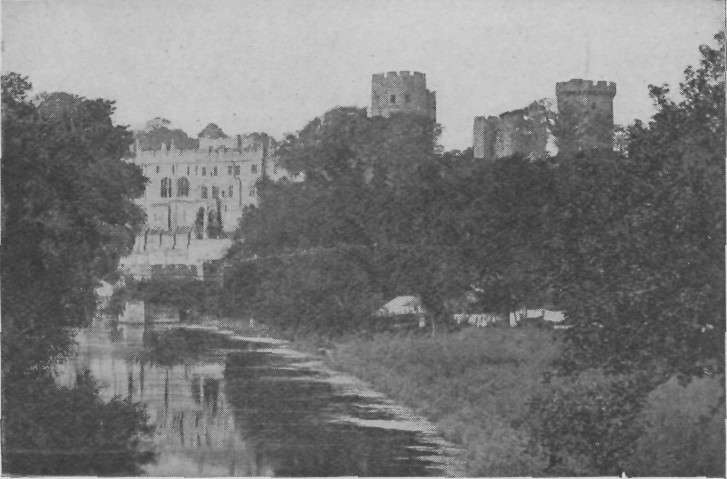

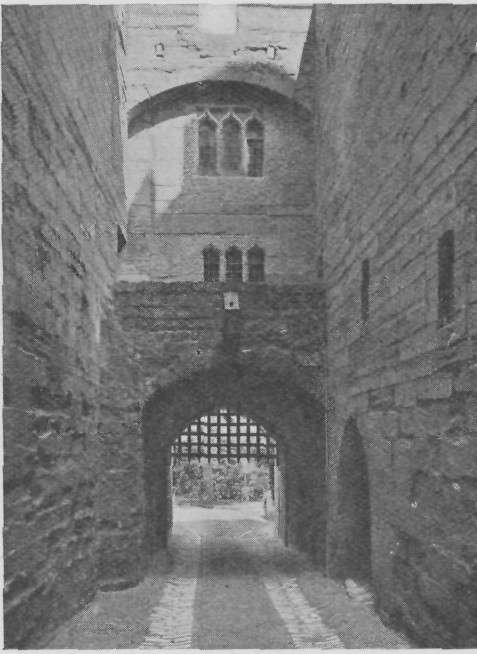

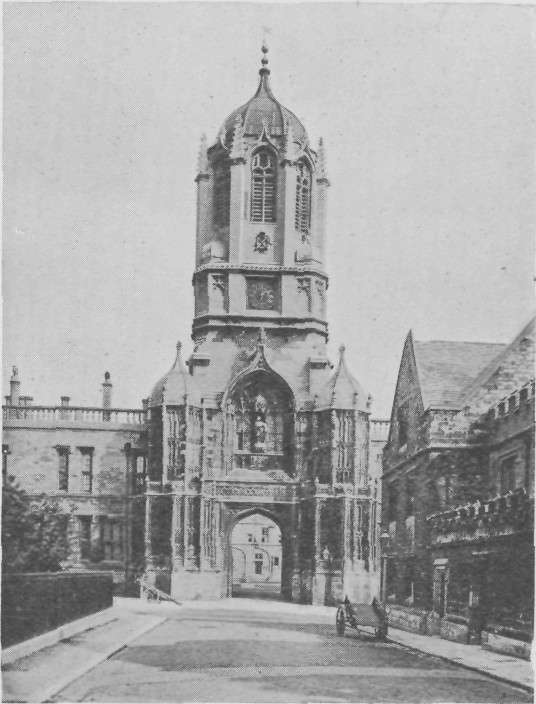

Castleton — Tideswell — Miller’s Dale — Flagg Moor — Newhaven — Tissington — Ashbourne ¶ River Dove — Mayfield — Ellastone — Alton Towers — Uttoxeter — Bagot’s Wood — Needwood Forest — Abbots Bromley — Handsacre ¶ Lichfield — Tamworth — Atherstone — Watling Street — Nuneaton ¶ Watling Street — High Cross — Lutterworth — River Swift — Fosse Way — Brinklow — Coventry ¶ Kenilworth — Leamington — Stoneleigh Abbey — Warwick — Stratford-on-Avon — Charlecote Park — Kineton — Edge Hill ¶ Banbury — Woodstock — Oxford ¶¶

SEVENTH WEEK’S JOURNEY

Monday, October 30th.

The Scots as a nation are proverbial for their travelling propensities; they are to be found not only in every part of the British Isles, but in almost every known and unknown part of the wide world. It was a jocular saying then in vogue that if ever the North Pole were discovered, a Scotsman would be found there sitting on the top! Sir Walter Scott was by no means behind his fellow countrymen in his love of travel, and like his famous Moss-troopers, whose raids carried them far beyond the Borders, even into foreign countries, he had not confined himself “to his own—his Native Land.” We were not surprised, therefore, wrhen we heard of him in the lonely neighbourhood of the Peak of Derbyshire, or that, although he had never been known to have visited the castle or its immediate surroundings, he had written a novel entitled Peveril of the Peak. This fact was looked upon as a good joke by his personal friends, who gave him the title of the book as a nickname, and Sir Walter, when writing to some of his most intimate friends, had been known to subscribe himself in humorous vein as “Peveril of the Peak.”

There were several objects of interest well worth seeing at Castleton besides the great cavern; there was the famous Blue John Mine, that took its name from the peculiar blue stone found therein, a kind of fibrous fluor-spar usually blue to purple, though with occasional black and yellow veins, of which ornaments were made and sold to visitors, and from which the large blue stone was obtained that formed the magnificent vase in Chatsworth House, the residence of the Duke of Devonshire, and in other noble mansions which possess examples of the craft. In the mine there were two caverns, one of them 100 feet and the other 150 feet high, “which glittered with sparkling stalactites.” Then there was the Speedwell Mine, one of the curiosities of the Peak, discovered by miners searching for ore, which they failed to find, although they laboured for years at an enormous cost. In boring through the rock, however, they came to a large natural cavern, now reached by descending about a hundred steps to a canal below, on which was a boat for conveying passengers to the other end of the canal, with only a small light or torch at the bow to relieve the stygian darkness. Visitors were landed on a platform to listen to a tremendous sound of rushing water being precipitated somewhere in the fearful and impenetrable darkness, whose obscurity and overpowering gloom could almost be felt. On the slope of the Eldon Hill there was also a fearful chasm called the Eldon Hole, where a falling stone was never heard to strike the bottom. This had been visited in the time of Queen Elizabeth by the Earl of Leicester, who caused an unfortunate native to be lowered into it to the full length of a long rope; when the poor fellow was drawn up again he was “stark mad,” and died eight days afterwards.

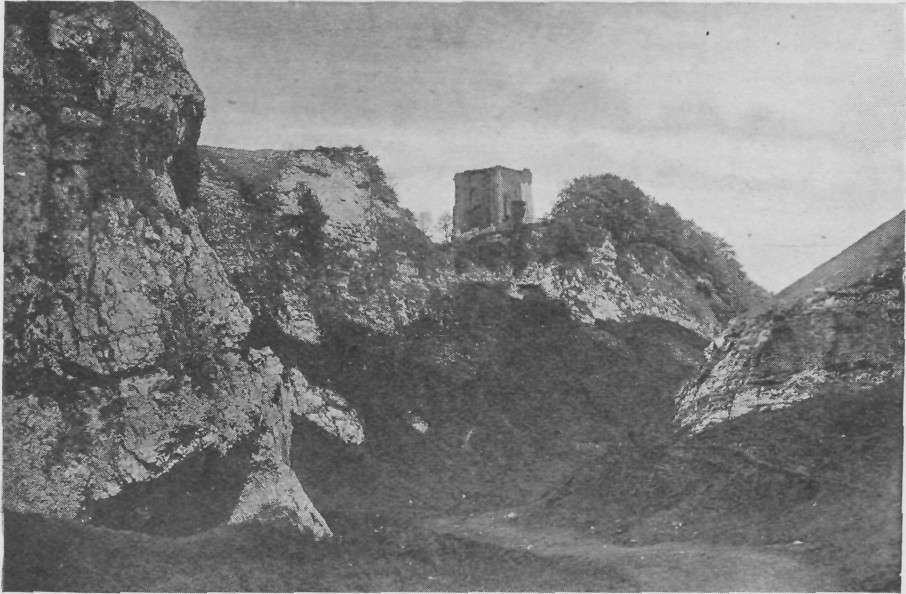

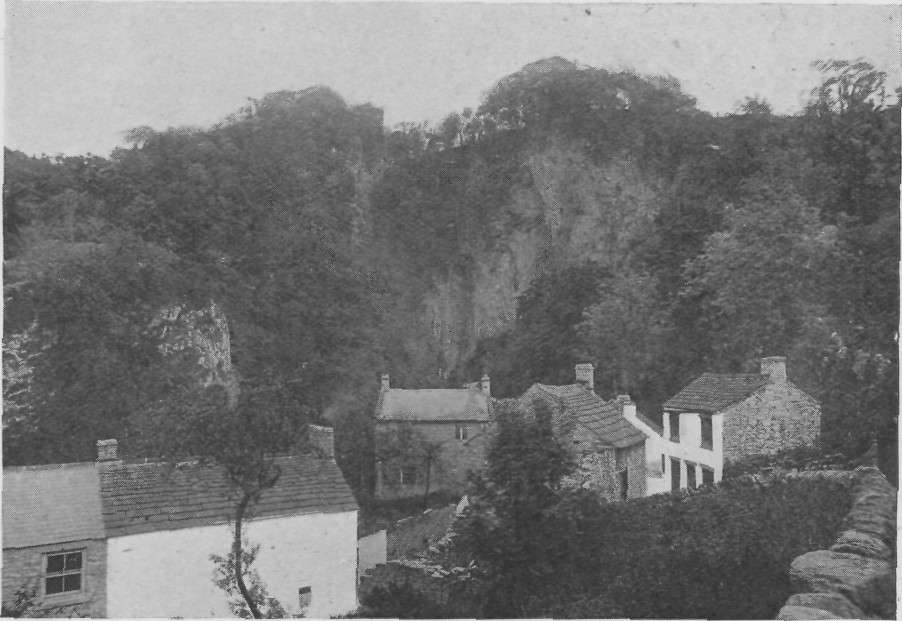

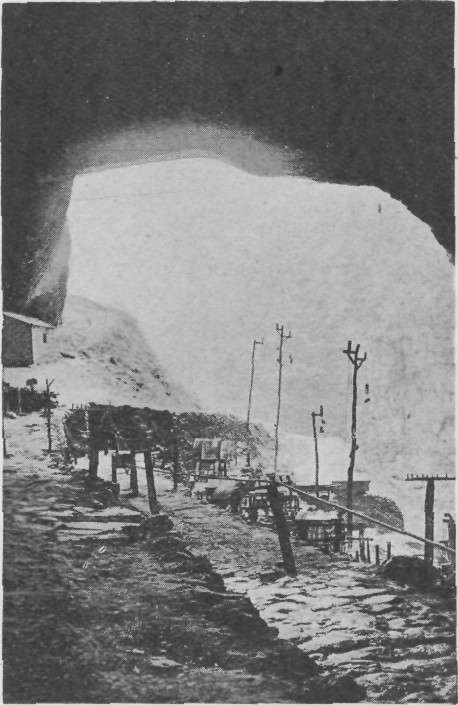

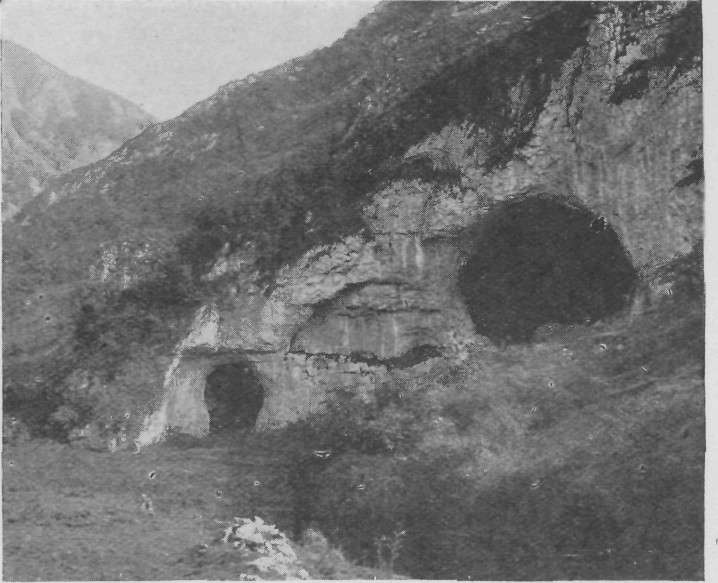

We had to leave all these attractions to a later visit, since we had come to Castleton to see the largest cavern of all, locally named the “Devil’s Hole,” but by polite visitors the “Peak Cavern.” The approach to the cavern was very imposing and impressive, perpendicular rocks rising on both sides to a great height, while Peveril Castle stood on the top of the precipice before us like a sentinel guarding entrance to the cavern, which was in the form of an immense Gothic arch 120 feet high, 42 feet wide, and said to be large enough to contain the Parish Church and all its belongings. This entrance, however, was being used as a rope-walk, where, early as it was, the workers were already making hempen ropes alongside the stream which flowed from the cavern, and the strong smell of hemp which prevailed as we stood for a few minutes watching the rope-makers was not at all unpleasant.

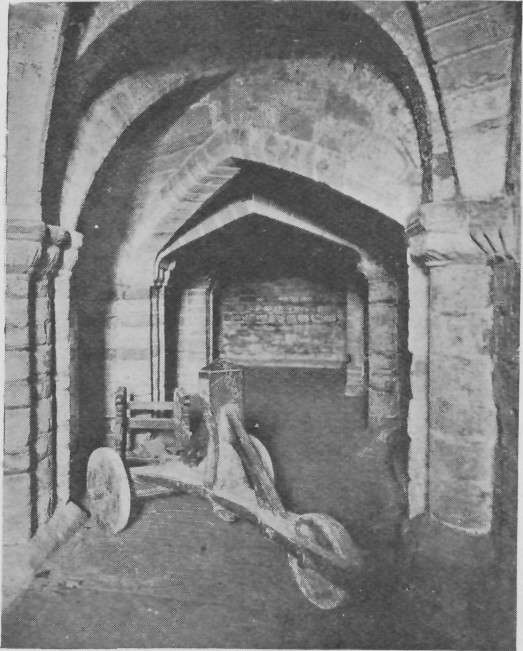

ROPE-WALK AT ENTRANCE INSIDE CAVE, CASTLETON, IN 1871.

If it had been the entrance to Hades, to which it had been likened by a learned visitor, we might have been confronted by Cerberus instead of our guide, whom our friends had warned overnight that his attendance would be required early this morning by distinguished visitors, who would expect the cave to be lit up with coloured lights in honour of their visit. The guide as he handed a light to each of us explained apologetically that his stock of red lights had been exhausted during the season, but he had brought a sufficient number of blue lights to suit the occasion. We followed him into the largest division of the cavern, which was 270 feet long and 150 feet high, the total length being about half a mile. It contained many other rooms or caves, into which he conducted us, the first being known as the Bell House, and here the path we had been following suddenly came to an end at an arch about five yards wide, where there was a stream called the River Styx, over which he ferried us in a boat, landing us in a cave called the Hall of Pluto, the Being who ruled over the Greek Hades, or Home of Departed Spirits, guarded by a savage three-headed dog named Cerberus. The only way of reaching the “Home,” our guide told us, was by means of the ferry on the River Styx, of which Charon had charge, and to ensure the spirit having a safe passage to the Elysian Fields it was necessary that his toll should be paid with a coin placed beforehand in the mouth or hand of the departed. We did not, however, take the hint about the payment of the toll until after our return journey, when we found ourselves again at the mouth of the Great Cavern, a privilege perhaps not extended to Pluto’s ghostly visitors, nor did we see any of those mysterious or mythological beings; perhaps the nearest approach to them was the figure of our guide himself, as he held aloft the blue torch he had in his hand when in the Hall of Pluto, for he presented the appearance of a man afflicted with delirium tremens or one of those “blue devils” often seen by victims of that dreadful disease. We also saw Roger Rain’s House, where it always rained, summer and winter, all the year round, and the Robbers’ Cave, with its five natural arches. But the strangest cave we visited was that called the “Devil’s Wine Cellar,” an awful abyss where the water rushed down a great hole and there disappeared. Her Most Gracious Majesty, Queen Victoria, visited the cavern in 1832, and one of the caves was named Victoria in memory of that event; we had the honour of standing on the exact spot where she stood on that occasion.

Our visit to the cavern was quite a success, enhanced as it was by the blue lights, so, having paid the guide for his services, we returned to our lodgings to “pack up” preparatory to resuming our walk. The white stones so kindly presented to my brother—of which he was very proud, for they certainly were very fine specimens—seemed likely to prove a white elephant to him. The difficulty now was how to carry them in addition to all the other luggage. Hurrying into the town, he returned in a few minutes with an enormous and strongly made red handkerchief like those worn by the miners, and in this he tied the stones, which were quite heavy and a burden in themselves. With these and all the other luggage as well he presented a very strange appearance as he toiled up the steep track through Cave Dale leading from the rear of the town to the moors above. It was no small feat of endurance and strength, for he carried his burdens until we arrived at Tamworth railway station in Staffordshire, to which our next box of clothes had been ordered, a distance of sixty-eight and a half miles by the way we walked. It was with a feeling of real thankfulness for not having been killed with kindness in the bestowal of these gifts that he deposited the stones in that box. When they reached home they were looked upon as too valuable to be placed on the rockeries and retained the sole possession of a mantelshelf for many years. My ankle was still very weak, and it was as much as I could do to carry the solitary walking-stick to assist me forwards; but we were obliged to move on, as we were now quite fifty miles behind our projected routine, and we knew there was some hard work before us. When we reached the moors, which were about a thousand feet above sea-level, the going was comparatively easy on the soft rich grass which makes the cow’s milk so rich, and we had some good views of the hills. That named Mam Tor was one of the “Seven wonders of the Peak,” and its neighbour, known as the Shivering Mountain, was quite a curiosity, as the shale, of which it was composed, was constantly breaking away and sliding down the mountain slope with a sound like that of falling water. Bagshawe Cavern was near at hand, but we did not visit it. It was so named because it had been found on land belonging to Sir William Bagshawe, whose lady christened its chambers and grottos with some very queer names. Across the moors we could see the town of Tideswell, our next objective, standing like an oasis in the desert, for there were no trees on the moors. We had planned that after leaving there we would continue our way across the moors to Newhaven, and then walk through Dove Dale to Ashbourne in the reverse direction to that taken the year before on our walk from London to Lancashire. Before reaching Tideswell we came to a point known as Lane Head, where six lane-ends met, and which we supposed must have been an important meeting-place when the moors, which surrounded it for miles, formed a portion of the ancient Peak Forest. We passed other objects of interest, including some ancient remains of lead mining in the form of curious long tunnels like sewers on the ground level which radiated to a point where on the furnaces heaps of timber were piled up and the lead ore was smelted by the heat which was intensified by these draught-producing tunnels.

When Peak Forest was in its primeval glory, and the Kings of England with their lords, earls, and nobles came to hunt there, many of the leading families had dwellings in the forest, and we passed a relic of these, a curious old mansion called Hazelbadge Hall, the ancient home of the Vernons, who still claim by right as Forester to name the coroner for West Derbyshire when the position falls vacant.

Tideswell was supposed to have taken its name from an ebbing and flowing well whose water rose and fell like the tides in the sea, but which had been choked up towards the end of the eighteenth century, and reopened in the grounds of a mansion, so that the cup-shaped hollow could be seen filling and emptying.

A market had existed at Tideswell since the year 1250, and one was being held as we entered the town, and the “George Inn,” where we called for refreshments, was fairly well filled with visitors of one kind or another.

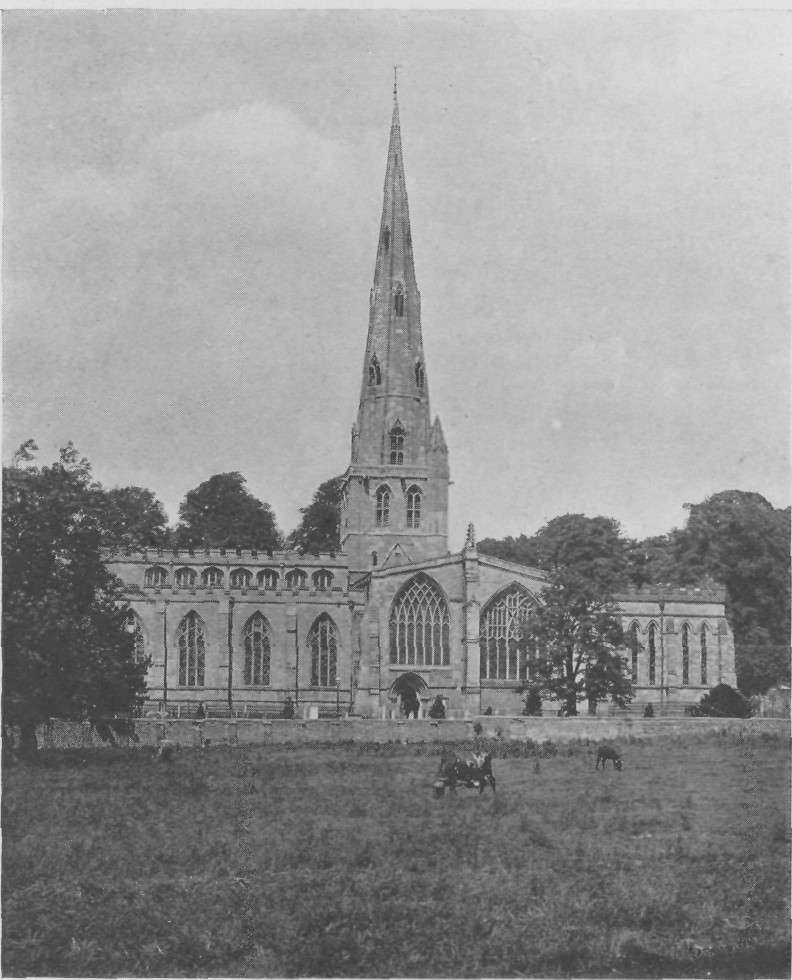

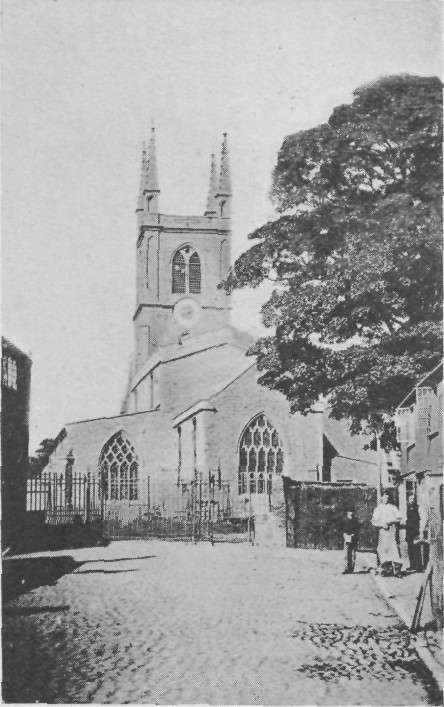

We left our luggage to the care of the ostler, and went to visit the fine old church adjacent, where many ancient families lie buried; the principal object of interest was the magnificent chancel, which has been described as “one Gallery of Light and Beauty,” the whole structure being known as the Cathedral of the Peak. There was a fine monumental brass, with features engraved on it which throw light on the Church ritual of the day, to the memory of Bishop Pursglove, who was a native of Tideswell and founder of the local Grammar School, who surrendered his Priory of Gisburn to Henry VIII in 1540, but refused, in 1559, to take the Oath of Supremacy. Sampson Meverill, Knight Constable of England, also lies buried in the chancel, and by his epitaph on a marble tomb, brought curiously enough from Sussex, he asks the reader “devoutly of your charity” to say “a Pater Noster with an Ave for all Xtian soules, and especially for the soule of him whose bones resten under this stone.” Meverill, with John Montagu, Earl of Shrewsbury, fought as “a Captain of diverse worshipful places in France,” serving under John, Duke of Bedford, in the “Hundred Years’ War,” and after fighting in eleven battles within the space of two years he won knighthood at the duke’s hands at St. Luce. In the churchyard was buried William Newton, the Minstrel of the Peak, and Samuel Slack, who in the last quarter of the eighteenth century was the most popular bass singer in England. When quite young Slack competed with others for a position in a college choir at Cambridge, and sang Purcell’s famous air, “They that go down to the sea in ships.” When he had finished, the Precentor rose immediately and said to the other candidates, “Gentlemen, I now leave it to you whether any one will sing after what you have just heard!” No one rose, and so Slack gained the position.

Soon afterwards Georgiana, Duchess of Sutherland, interested herself in him, and had him placed under Spofforth, the chief singing master of the day, under whose tuition he greatly improved, taking London by storm. He was for many years the principal bass at all the great musical festivals. So powerful was his voice, it is said, that on one occasion when he was pursued by a bull he uttered a bellow which so terrified the animal that it ran away, so young ladies who were afraid of these animals always felt safe when accompanied by Mr. Slack. When singing before King George III at Windsor Castle, he was told that His Majesty had been pleased with his singing. Slack remarked in his Derbyshire dialect, which he always remembered, “Oh, he was pleased, were he? I thow’t I could do’t.” Slack it was said made no effort to improve himself either in speech or in manners, and therefore it was thought that he preferred low society.

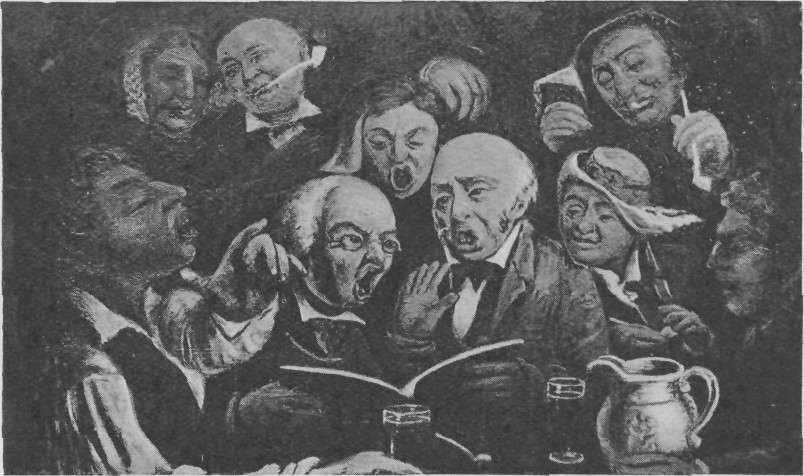

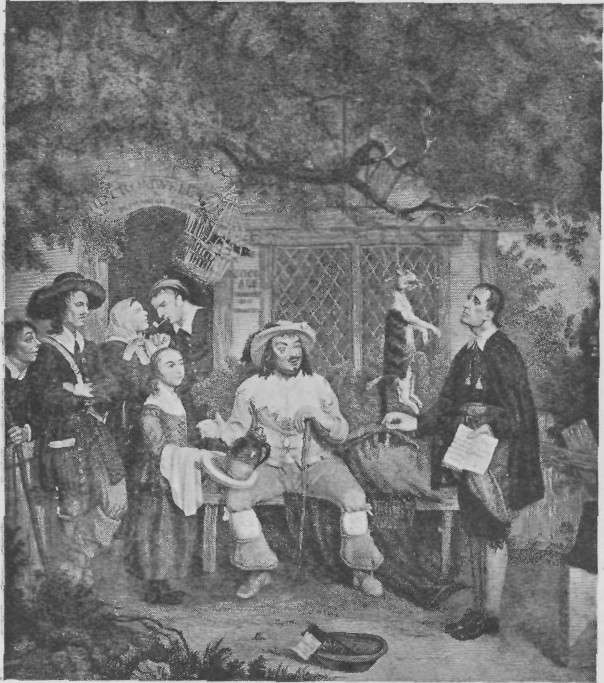

When he retired and returned to his native village he was delighted to join the local “Catch and Glee Club,” of which he soon became the ruling spirit. It held its meetings at the “George Inn” where we had called for refreshments, and we were shown an old print of the club representing six singers in Hogarthian attitudes with glasses, jugs, and pipes, with Slack and his friend Chadwick of Hayfield apparently singing heartily from the same book Slack’s favourite song, “Life’s a Bumper fill’d by Fate.” Tideswell had always been a musical town; as far back as the year 1826 there was a “Tideswell Music Band,” which consisted of six clarionets, two flutes, three bassoons, one serpent, two trumpets, two trombones, two French horns, one bugle, and one double drum—twenty performers in all.

They had three practices weekly, and there were the usual fines for those who came late, or missed a practice, for inattention to the leader, or for a dirty instrument, the heaviest fine of all being for intoxication. But long after this there was a Tideswell Brass Band which became famous throughout the country, for the leader not only wrote the score copies for his own band, but lithographed and sold them to other bands all over the country.

We were particularly interested in all this, for my brother had for the past eight years indulged in the luxury of a brass band himself. The band consisted of about twenty members when in full strength, and as instruments were dear in those days it was a most expensive luxury, and what it had cost him in instruments, music, and uniforms no one ever knew. He had often purchased “scores” from Metcalf, the leader of the Tideswell Band, a fact that was rather a source of anxiety to me, as I knew if he called to see Metcalf our expedition for that day would be at an end, as they might have conversed with each other for hours. I could not prevent him from relating at the “George” one of his early reminiscences, which fairly “brought down the house,” as there were some musicians in the company.

His band had been formed in 1863, and consisted of about a dozen performers. Christmas time was coming on, when the bandsmen resolved to show off a little and at the same time collect some money from their friends to spend in the New Year. They therefore decided that the band should go out “busking” each evening during Christmas week. They had only learned to play five tunes—two of them belonging to well-known hymns, a third “God Save the Queen,” while the remaining two were quicksteps, one of which was not quite perfectly learned.

They were well received in the village, and almost every house had been visited with the exception of the Hall, which was some distance away, and had been left till the last probably owing to the fact that the squire was not particularly noted for his liberality. If, however, he had been at home that week, and had any sense of music, he would have learned all their tunes off by heart, as the band must have been heard clearly enough when playing at the farms surrounding the mansion.

To avoid a possibility of giving offence, however, it was decided to pay him a visit; so the band assembled one evening in front of the mansion, and the conductor led off with a Psalm tune, during which the Hall door was opened by a servant. At this unexpected compliment expectations rose high amongst the members of the band, and a second Psalm tune was played, the full number of verses in the hymn being repeated. Then followed a pause to give the squire a chance of distinguishing himself, but as he failed to rise to the occasion it was decided to play a quickstep. This was followed by a rather awkward pause, as there were some high notes in the remaining quickstep which the soprano player said he was sure he could not reach as he was getting “ramp’d” already. At this moment, however, the situation was relieved by the appearance of a female servant at the door.

The member of the band who had been deputed to collect all donations at once went to the door, and all eyes were turned upon him when he came back towards the lawn, every member on tip-toe of expectation. But he had only returned to say that the squire’s lady wished the band to play a polka. This spread consternation throughout the band, and one of the younger members went to the conductor saying, “A polka! A polka! I say, Jim, what’s that?” “Oh,” replied the conductor, “number three played quick!” Now number three was a quickstep named after Havelock the famous English General in India, so “Havelock’s March played quick” had to do duty for a polka; but the only man who could play it quickly was the conductor himself, who after the words, “Ready, chaps!” and the usual signal “One-two-three,” dashed off at an unusual speed, the performers following as rapidly as they could, the Bombardon and the Double B, the biggest instruments, finishing last with a most awful groan, after which the conductor, who couldn’t stop laughing when once he started, was found rolling on the lawn in a kind of convulsion. It took them some time to recover their equilibrium, during which the Hall door remained open, and a portion of the band had already begun to move away in despair, when they were called back by the old butler appearing at the Hall door with a silver tray in his hand. The collector’s services were again requisitioned, and he returned with the magnificent sum of one shilling! As most of the farmers had given five shillings and the remainder half a crown, the squire’s reputation for generosity had been fully maintained. One verse of “God save the Queen,” instead of the usual three, was played by the way of acknowledgment, and so ended the band’s busking season in the year 1863.

We quite enjoyed our visit to Tideswell, and were rather loath to leave the friendly company at the “George Inn,” who were greatly interested in our walk, several musical members watching our departure as the ostler loaded my brother with the luggage.

Tideswell possessed a poet named Beebe Eyre, who in 1854 was awarded £50 out of the Queen’s Royal Bounty, which probably inspired him to write:

Tideswell! thou art my natal spot,

And hence I love thee well;

May prosperous days now be the lot

Of all that in thee dwell!

The sentiments expressed by the poet coincided with our own. As we departed from the town we observed a curiosity in the shape of a very old and extremely dilapidated building, which we were informed could neither be repaired, pulled down, nor sold because it belonged to some charity.

On the moors outside the town there were some more curious remains of the Romans and others skilled in mining, which we thought would greatly interest antiquarians, as they displayed more methods of mining than at other places we had visited. A stream had evidently disappointed them by filtering through its bed of limestone, but this they had prevented by forming a course of pebbles and cement, which ran right through Tideswell, and served the double purpose of a water supply and a sewer.

We crossed the old “Rakes,” or lines, where the Romans simply dug out the ore and threw up the rubbish, which still remained in long lines. Clever though they were, they only knew lead when it occurred in the form known as galena, which looked like lead itself, and so they threw out a more valuable ore, cerusite, or lead carbonate, and the heaps of this valuable material were mined over a second time in comparatively recent times. The miner of the Middle Ages made many soughs to drain away the water from the mines, and we saw more of the tunnels that had been made to draw air to the furnaces when wood was used for smelting the lead.

The forest, like many others, had disappeared, and Anna Seward had exactly described the country we were passing through when she wrote:

The long lone tracks of Tideswell’s native moor,

Stretched on vast hills that far and near prevail.

Bleak, stony, bare, monotonous, and pale.

The poet Newton had provided the town with a water supply by having pipes laid at his own expense from the Well Head at the source of the stream which flowed out of an old lead-mine. Lead in drinking-water has an evil name for causing poisoning, but the Tideswell folk flourish on it, since no one seems to think of dying before seventy, and a goodly number live to over ninety.

They have some small industries, cotton manufacture having spread from Lancashire into these remote districts. It is an old-fashioned place, with houses mostly stuccoed with broken crystals and limestone from the “Rakes” and containing curiously carved cupboard doors and posts torn from churches ornamented in Jacobean style by the sacrilegious Cromwellians, many of them having been erected just after the Great Rebellion.

BRIDGE CARRYING THE CANAL OVERHEAD.

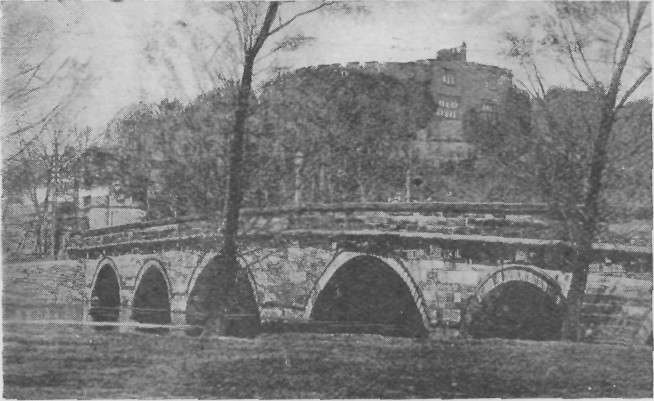

We now journeyed along the mountain track until it descended sharply into Miller’s Dale; but before reaching this place we were interested in the village of Formhill, where Brindley, the famous canal engineer, was born in 1716. Brindley was employed by the great Duke of Bridgewater, the pioneer of canal-making in England, to construct a canal from his collieries at Worsley, in Lancashire, to Manchester, in order to cheapen the cost of coal at that important manufacturing centre. It was an extraordinary achievement, considering that Brindley was quite uneducated and knew no mathematics, and up to the last remained illiterate. Most of his problems were solved without writings or drawings, and when anything difficult had to be considered, he would go to bed and think it out there. At the Worsley end it involved tunnelling to the seams of coal where the colliers were at work so that they could load the coal directly into the boats. He constructed from ten to thirteen miles of underground canals on two different levels, with an ingeniously constructed connection between the two. After this he made the great Bridgewater Canal, forty miles in length, from Manchester to Runcorn, which obtained a fall of one foot per mile by following a circuitous route without a lock or a tunnel in the whole of its course until it reached its terminus at the River Mersey. In places where a brook or a small valley had to be crossed the canal was carried on artificially raised banks, and to provide against a burst in any of these, which would have caused the water to run out of the canal, it was narrowed at each end of the embankment so that only one boat could pass through at a time, this narrow passage being known as a “stop place.” At the entrance to this a door was so placed at the bottom of the canal that if any undue current should appear, such as would occur if the embankment gave way, one end of it would rise into a socket prepared for it in the stop-place, and so prevent any water leaving the canal except that in the broken section, a remedy simple but ingenious. On arriving at Runcorn the boats were lowered by a series of locks into the River Mersey, a double service of locks being provided so that boats could pass up and down at the same time and so avoid delay.

When the water was first turned into the canal, Brindley mysteriously disappeared, and was nowhere to be found; but as the canal when full did not burst its embankments, as he had feared, he soon reappeared and was afterwards employed to construct even more difficult canals. He died in 1772, and was buried in Harriseahead Churchyard on the Cheshire border of Staffordshire. It is computed that he engineered as many miles of canals as there are days in the year.

It must have been a regular custom for the parsons in Derbyshire to keep diaries in the eighteenth century, for the Vicar of Wormhill kept one, like the Vicar of Castleton, both chancing to be members of the Bagshawe family, a common name in that neighbourhood. He was a hard-working and conscientious man, and made the following entry in it on February 3rd, 1798

Sunday.—Preached at Wormhill on the vanity of human pursuits and human pleasures, to a polite audience, an affecting sermon. Rode in the evening to Castleton, where I read three discourses by Secker. In the forest I was sorry to observe a party of boys playing at Football. I spoke to them but was laughed at, and on my departure one of the boys gave the football a wonderful kick—a proof this of the degeneracy of human nature!

On reaching Miller’s Dale, a romantic deep hollow in the limestone, at the bottom of which winds the fast-flowing Wye, my brother declared that he felt more at home, as it happened to be the only place he had seen since leaving John o’ Groat’s that he had previously visited, and it reminded him of a rather amusing incident.

THE BRIDGEWATER CANAL—WHERE IT ENTERS THE MINES AT WORSLEY.

Our uncle, a civil engineer in London, had been over on a visit, and was wearing a white top-hat, then becoming fashionable, and as my brother thought that a similar hat would just suit the dark blue velveteen coat he wore on Sundays, he soon appeared in the prevailing fashion. He was walking from Ambergate to Buxton, and had reached Miller’s Dale about noon, just as the millers were leaving the flour mills for dinner. One would have thought that the sight of a white hat would have delighted the millers, but as these hats were rather dear, and beyond the financial reach of the man in the street, they had become an object of derision to those who could not afford to wear them, the music-hall answer to the question “Who stole the donkey?” being at that time “The man with the white hat!”

He had met one group of the millers coming up the hill and another lot was following, when a man in the first group suddenly turned round and shouted to a man in the second group, “I say, Jack, who stole the donkey?” But Jack had not yet passed my brother, and, as he had still to face him, he dared not give the customary answer, so, instead of replying “The man with the white hat,” he called out in the Derbyshire dialect, with a broad grin on his face, “Th’ feyther.” A roar of laughter both behind and in front, in which my brother heartily joined, followed this repartee.

Probably some of the opprobrium attached to the white hat was because of its having been an emblem of the Radicals. We had seen that worn by Sir Walter Scott in his declining days, but we could not think of including him in that extreme political party, though its origin dated back to the time when he was still alive. Probably the emblem was only local, for it originated at Preston in Lancashire, a place we knew well, commonly called Proud Preston, no doubt by reason of its connection with the noble family of Stanley, who had a mansion in the town. Preston was often represented in Parliament by a Stanley, and was looked upon as a Pocket Borough. In the turbulent times preceding the Abolition of the Corn Laws a powerful opponent, in the person of Mr. Henry Hunt, a demagogue politician, who had suffered imprisonment for advocating Chartism, appeared at the Preston election of 1830 to oppose the Honourable E.G. Stanley, afterwards Earl of Derby. He always appeared wearing a white hat, and was an eloquent speaker, and for these reasons earned the sobriquet of “Orator” Hunt and “Man with the White Hat.” The election contest was one of the most exciting events that ever occurred in Preston, and as usual the children took their share in the proceedings, those on Mr. Stanley’s side parading the streets singing in a popular air:

Hey! Ho! Stanley for Ever! Stanley for Ever!

Hey! Ho! Stanley for Ever Ho!

Stanley, Stanley, Stanley, Ho!

Stanley is my honey Ho!

When he weds he will be rich,

He will have a coach and six.

Then followed the chorus to the accompaniment of drums and triangles:

Hey! Ho! Stanley for Ever, Ho!

In spite of this, however, and similar ditties, “Orator Hunt,” by a total vote of 3,730, became M.P. for Preston, and it was said that it was through this incident that the Radicals adopted the White Hat as their emblem.

Lord Derby was so annoyed at the result of the election that he closed his house, which stood across the end of a quiet street, and placed a line of posts across it, between which strong chains were hung, and on which my brother could remember swinging when a boy.

One of our uncles was known as the “Preston Poet” at that time, and he wrote a poem entitled “The Poor, God Bless ‘Em!” the first verse reading:

Let sycophants bend their base knees in the court

And servilely cringe round the gate,

And barter their honour to earn the support

Of the wealthy, the titled, the great;

Their guilt piled possessions I loathe, while I scorn

The knaves, the vile knaves who possess ’em;

I love not to pamper oppression, but mourn

For the poor, the robb’d poor—God bless ’em!

A striking contrast to the volubility of Mr. Hunt was Mr. Samuel Horrocks, also M.P. for Preston, whose connection with the “Big Factory” in Preston probably gained him the seat. He was said to have been the “quiet Member,” never known to make a speech in the House of Commons, unless it was to ask some official to close a window. The main thoroughfare in Preston was Fishergate, a wide street, where on one Saturday night two men appeared walking up the middle of the street, carrying large papers suspended over their arms and shouting at the top of their voices.

“The Speech of Samuel Horrocks, Esquire, M.P., in the British House of Commons! one penny,” which they continued to repeat.

“Eh! owd Sammy’s bin makkin’ a speech,” and a rush was made for the papers. The streets were poorly lighted in those days, and the men did a roaring business in the dark. One man, however, was so anxious to read the speech that he could not wait until he got home, but went to a shop window, where there was a light, but the paper was blank. Thinking they had given him the wrong paper, he ran after the men and shouted, pointing to the paper, “Hey, there’s nowt on it.” “Well,” growled one of the men, “he said nowt.”

We now climbed up the opposite side of the dale, and continued on the moorland road for a few miles, calling at the “Flagg Moor Inn” for tea. By the time we had finished it was quite dark, and the landlady of the inn did her best to persuade us to stay there for the night, telling us that the road from there to Ashbourne was so lonely that it was possible on a dark night to walk the whole distance of fourteen miles without seeing a single person, and as it had been the Great Fair at Newhaven that day, there might be some dangerous characters on the roads. When she saw we were determined to proceed farther, she warned us that the road did not pass through any village, and that there was only a solitary house here and there, some of them being a little way from the road. The road was quite straight, and had a stone wall on each side all the way, so all we had got to do was to keep straight on, and to mind we did not turn to the right or the left along any of the by-roads lest we should get lost on the moors. It was not without some feeling of regret that we bade the landlady “Good night” and started out from the comfortable inn on a pitch-dark night. Fortunately the road was dry, and, as there were no trees, the limestone of which it was composed showed a white track easily discernible in the inky darkness which surrounded it. As we got farther on our way we could see right in front a great illumination in the mist or clouds above marking the glare from the country fair at Newhaven, which was only four miles from the inn we had just left. We met quite a number of people returning from the fair, both on foot and in vehicles, and as they all appeared to be in good spirits we received a friendly greeting from all who spoke to us. Presently arriving at Newhaven itself, which consisted solely of one large inn, we found the surrounding open space packed with a noisy and jovial crowd of people, the number of whom absolutely astonished us, as the country around appeared so desolate, and we wondered where they all could have come from. Newhaven, which had been a very important place in the coaching-days, was a big three-storeyed house with twenty-five bedrooms and stabling for a hundred horses. It stood at a junction of roads about 1,100 feet above sea-level in a most lonely place, and in the zenith of its popularity there was seldom a bedroom empty, the house being quite as gay as if it had been in London itself. It had been specially built for the coach traffic by the then Duke of Devonshire, whose mansion, Chatsworth House, was only a few miles distant. King George IV stayed at Newhaven on one occasion, and was so pleased with his entertainment that he granted to the inn a free and perpetual licence of his own sovereign pleasure, so that no application for renewal of licence at Brewster Sessions was ever afterwards required; a fact which accounted in some measure for the noisy company congregated therein, in defiance of the superintendent of police, who, with five or six of his officers, was standing in front of the fair. Booths had been erected by other publicans, but the police had ordered these to be removed earlier in the day to prevent further disturbances.

We noticed they had quite a number of persons in custody, and when I saw a policeman looking very critically at the miscellaneous assortment of luggage my brother was carrying, I thought he was about to be added to the number; but he was soon satisfied as to the honesty of his intentions. The “New Haven” must have meant a new haven for passengers, horses, and coaches when the old haven had been removed, as the word seemed only to apply to the hotel, which, as it was ten miles both from Buxton and Ashbourne, and also on the Roman road known as Via Gellia, must have been built exactly to accommodate the ten-mile run of the coaches either way. It quite enlivened us to see the old-fashioned shows, the shooting-boxes, the exhibitions of monstrosities, with stalls displaying all sorts of nuts, sweets, gingerbreads, and all the paraphernalia that in those days comprised a country fair, and we should have liked to stay at the inn and visit some of the shows which were ranged in front of it and along the green patches of grass which lined the Ashbourne road; but in the first place the inn was not available, and in the second our twenty-five-mile average daily walk was too much in arrears to admit of any further delay.

All the shows and stalls were doing a roaring trade, and the naphtha lamps with which they were lighted flared weirdly into the inky darkness above. Had we been so minded, we might have turned aside and found quarters at an inn bearing the odd sign of “The Silent Woman” (a woman with her head cut off and tucked under her arm, similar to one nearer home called the “Headless Woman”—in the latter case, however, the tall figure of the woman was shown standing upright, without any visible support, while her head was calmly resting on the ground—the idea seeming to be that a woman could not be silent so long as her head was on her body), but we felt that Ashbourne must be reached that night, which now seemed blacker than ever after leaving the glaring lights in the Fair. Nor did we feel inclined to turn along any by-road on a dark night like that, seeing that we had been partly lost on our way from London the previous year, nearly at the same place, and on quite as dark a night. On that memorable occasion we had entered Dovedale near Thorpe, and visited the Lovers’ Leap, Reynard’s Cave, Tissington Spires, and Dove Holes, but darkness came on, compelling us to leave the dale to resume our walk the following morning. Eventually we saw a light in the distance, where we found a cottage, the inmates of which kindly conducted us with a lantern across a lonely place to the village of Parwich, which in the Derbyshire dialect they pronounced “Porritch,” reminding us of our supper.

It was nearly closing-time when we were ushered into the taproom of the village inn among some strange companions, and when the hour of closing arrived we saw the head of the village policeman appear at the shutter through which outside customers were served with beer. The landlord asked him, “Will you have a pint?” Looking significantly at ourselves, he replied, “No, thank you,” but we noticed the “pint” was placed in the aperture, and soon afterwards disappeared!

At Newhaven we ascertained that we were now quite near Hartington and Dovedale. Hartington was a famous resort of fishermen and well known to Isaak Walton, the “Father of Fishermen,” and author of that famous book The Compleat Angler or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation, so full of such cheerful piety and contentment, such sweet freshness and simplicity, as to give the book a perennial charm. He was a great friend of Charles Cotton of Beresford Hall, who built a fine fishing-house near the famous Pike Pool on the River Dove, over the arched doorway of which he placed a cipher stone formed with the combined initials of Walton and himself, and inscribed with the words “Piscatoribus Sacrum.” It was said that when they came to fish in the fish pool early in the morning, Cotton smoked tobacco for his breakfast!

What spot more honoured than this beautiful place?

Twice honoured truly. Here Charles Cotton sang,

Hilarious, his whole-hearted songs, that rang

With a true note, through town and country ways,

While the Dove trout—in chorus—splashed their praise.

Here Walton sate with Cotton in the shade

And watched him dubb his flies, and doubtless made

The time seem short, with gossip of old days.

Their cyphers are enlaced above the door,

And in each angler’s heart, firm-set and sure.

While rivers run, shall those two names endure,

Walton and Cotton linked for evermore—-

And Piscatoribus Sacrum where more fit

A motto for their wisdom worth and wit?

Say, where shall the toiler find rest from his labours,

And seek sweet repose from the overstrung will?

Away from the worry and jar of his neighbours

Where moor-tinted streamlets flow down from the hill.

Then hurrah! jolly anglers, for burn and for river.

The songs of the birds and the lowing of kine:

The voice of the river shall soothe us for ever,

Then here’s to the toast, boys—”The rod and the line!”

We walked in the darkness for about six miles thinking all the time of Dovedale, which we knew was running parallel with our road at about two miles’ distance. When we reached Tissington, about three miles from Ashbourne, the night had become lighter, and there ought to have been a considerable section of the moon visible if the sky had been clear. Here we came to quite a considerable number of trees, but the village must have been somewhere in the rear of them. Well-dressing was a custom common in Derbyshire, and also on a much smaller scale in some of the neighbouring counties; but this village of Tissington was specially noted in this respect, for it contained five wells, all of which had to be dressed. As the dressers of the different wells vied with each other which should have the best show, the children and young people had a busy time in collecting the flowers, plants, buds, and ferns necessary to form the display. The festival was held on Holy Thursday, and was preceded with a service in the church followed by one at each of the wells, and if the weather was fine, hundreds of visitors assembled to criticise the work at the different wells. The origin of well-dressing is unknown, but it is certainly of remote antiquity, probably dating back to pagan times. That at Tissington was supposed to have developed at the time of the Black Plague in the fourteenth century, when, although it decimated many villages in the neighbourhood, it missed Tissington altogether—because, it was supposed, of the purity of the waters. But the origin of well-dressing must have been of much greater antiquity: the custom no doubt had its beginnings as an expression of praise to God from whom all blessings flow. The old proverb, “We never know the value of water till the well runs dry,” is singularly appropriate in the hilly districts of Derbyshire, where not only the wells, but the rivers also have been known to dry up, and when the spring comes and brings the flowers, what could be more natural than to thank the Almighty who sends the rain and the water, without which they could not grow.

We were sorry to have missed our walk down Dove Dale, but it was all for the best, as we should again have been caught in the dark there, and perhaps I should have injured my foot again, as the path along the Dale was difficult to negotiate even in the daylight. In any case we were pleased when we reached Ashbourne, where we had no difficulty in finding our hotel, for the signboard of the “Green Man” reached over our heads from one side of the main street to the other.

(Distance walked twenty-six and a half miles.)

Tuesday, October 31st.

The inn we stayed at was a famous one in the days of the stagecoaches, and bore the double name “The Green Man and the Black’s Head Royal Hotel” on a sign which was probably unique, for it reached across the full width of the street. A former landlord having bought another coaching-house in the town known as the “Black’s Head,” transferred the business to the “Green Man,” when he incorporated the two signs. We were now on the verge of Dr. Johnson’s country, the learned compiler of the great dictionary, who visited the “Green Man” in company with his companion, James Boswell, whose Life of Dr. Johnson is said to be the finest biography ever written in the English language. They had a friend at Ashbourne, a Dr. Taylor, whom they often visited, and on one occasion when they were all sitting in his garden their conversation turned on the subject of the future state of man. Johnson gave expression to his views in the following words, “Sir, I do not imagine that all things will be made clear to us immediately after death, but that the ways of Providence will be explained to us very gradually.”

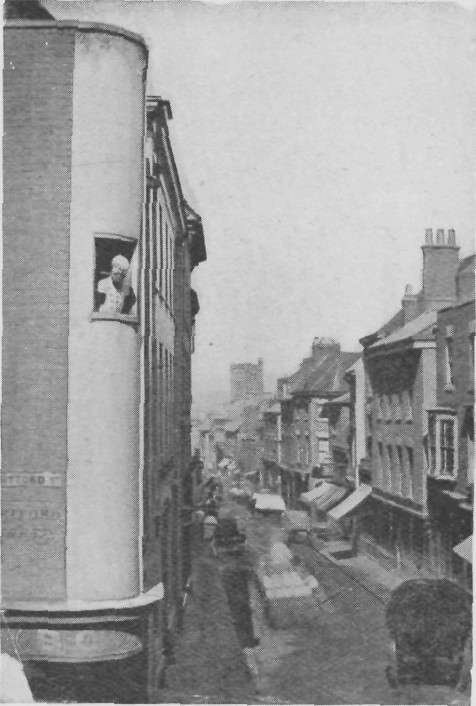

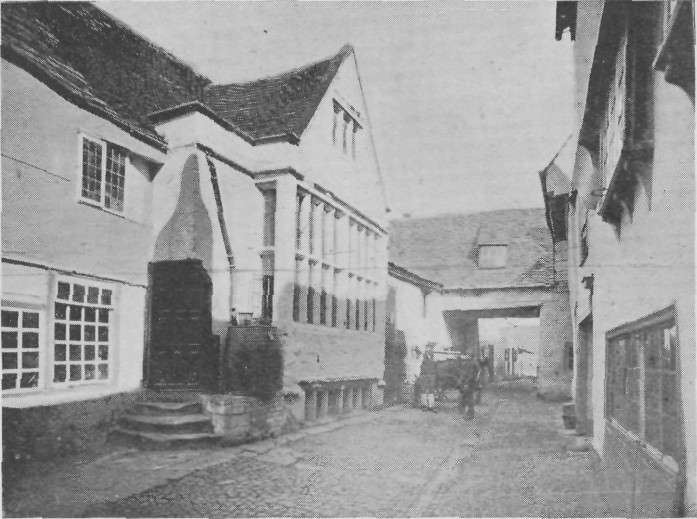

“THE GREEN MAN AND BLACK’S HEAD.”

Boswell stayed at the “Green Man” just before journeying with Dr. Johnson to Scotland, and was greatly pleased by the manners of the landlady, for he described her as a “mighty civil gentlewoman” who curtseyed very low as she gave him an engraving of the sign of the house, under which she had written a polite note asking for a recommendation of the inn to his “extensive acquaintance, and her most grateful thanks for his patronage and her sincerest prayers for his happiness in time and in blessed eternity.” The present landlady of the hotel appeared to be a worthy successor to the lady who presided there in the time of Boswell, for we found her equally civil and obliging, and, needless to say, we did justice to a very good breakfast served up in her best style.

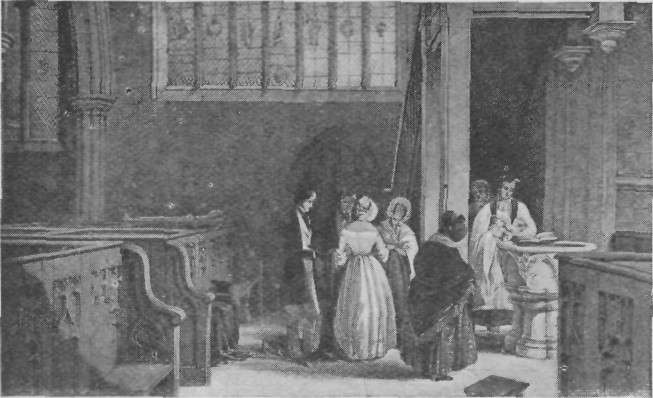

IN ASHBOURNE CHURCH IN YE OLDEN TIME.

The Old Hall of Ashbourne, situated at the higher end of the town, was a fine old mansion, with a long history, dating from the Cockayne family, who were in possession of lands here as early as the year 1372, and who were followed by the Boothby family.

The young Pretender, “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” who had many friends in England, stayed a night at the Hall in 1745, and the oak door of the room in which he slept was still preserved. He and his Highlanders never got farther than Derby, when he had to beat a hurried retreat, pursued by the Duke of Cumberland. Prince Charlie, to avoid the opposing army at Stafford and Lichfield, turned aside along the Churnet valley, through Leek, and so to Ashbourne. At Derby he called a Council of War, and learned how the Royal forces were closing in upon him, so that reluctantly a retreat was ordered. Then began a period of plundering and rapine. The Highlanders spread over the country, but on their return never crossed into Staffordshire, for, as the story goes, the old women of the Woodlands of Needwood Forest undertook to find how things were going, and crept down to the bridges of Sudbury and Scropton. As it began to rain, they used their red flannel petticoats as cloaks, which the Highlanders, spying, took to be the red uniforms of soldiers, and a panic seized them—so much so, that some who had seized some pig-puddings and were fastening them hot on a pole, according to a local ditty, ran out through a back door, and, jumping from a heap of manure, fell up to the neck in a cesspool. The pillage near Ashbourne was very great, but they could not stay, for the Duke was already at Uttoxoter with a small force.

George Canning, the great orator who was born in 1770 and died when he was Prime Minister of England in 1827, often visited Ashbourne Old Hall. In his time the town of Ashbourne was a flourishing one; it was said to be the only town in England that benefited by the French prisoners of war, as there were 200 officers, including three generals, quartered there in 1804, and it was estimated that they spent nearly £30,000 in Ashbourne. An omnibus was then running between Ashbourne and Derby, which out of courtesy to the French was named a “diligence,” the French equivalent for stage-coach; but the Derby diligence was soon abbreviated to the Derby “Dilly.” The roads at that time were very rough, macadamised surfaces being unknown, and a very steep hill leading into the Ashbourne and Derby Road was called bête noire by the French, about which Canning, who was an occasional passenger, wrote the following lines:

So down the hill, romantic Ashbourne, glides

The Derby Dilly, carrying three insides;

One in each corner sits and lolls at ease,

With folded arms, propt back and outstretched knees;

While the pressed bodkin, pinched and squeezed to death,

Sweats in the midmost place and scolds and pants for breath.

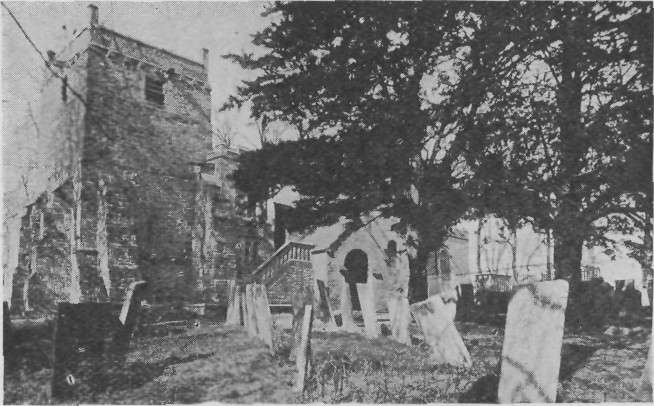

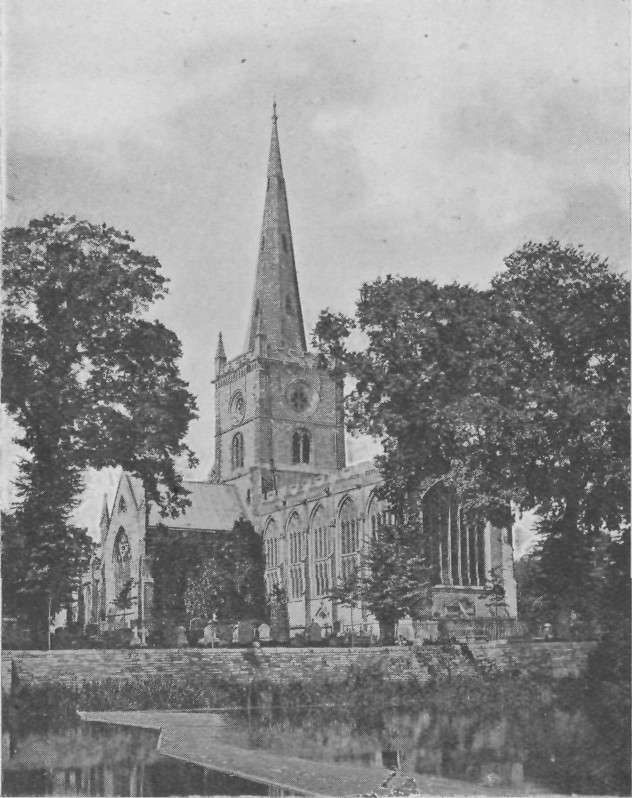

We were now at the end of the last spur of the Pennine Range of hills and in the last town in Derbyshire. As if to own allegiance to its own county, the spire of the parish church, which was 212 feet high, claimed to be the “Pride of the Peak.” In the thirteenth-century church beneath it, dedicated to St. Oswald, there were many fine tombs of the former owners of the Old Hall at Ashbourne, those belonging to the Cockayne family being splendid examples of the sculptor’s art. We noted that one member of the family was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1404, while another had been knighted by King Henry VII at the siege of Tournay. The finest object in the church was the marble figure of a little child as she appeared—

Before Decay’s effacing fingers

Have swept the lines where beauty lingers,

which for simplicity, elegance, and childlike innocence of face was said to be the most interesting and pathetic monument in England. It is reputed to be the masterpiece of the English sculptor Thomas Banks, whose work was almost entirely executed abroad, where he was better known than in England. The inscriptions on it were in four different languages, English, Italian, French, and Latin, that in English being:

I was not in safety, neither had I rest, and the trouble came.

The dedication was inscribed:

TO PENELOPE

ONLY CHILD OF SIR BROOKE BOOTHBY AND DAME SUSANNAH BOOTHBY.

Born April 11th 1785, died March 13th 1791.

She was in form and intellect most exquisite

The unfortunate parents ventured their all in this Frail bark,

And the wreck was Total.

The melancholy reference to their having ventured their all bore upon the separation between the father and mother, which immediately followed the child’s death.

The description of the monument reads as follows:

The figure of the child reclines on a pillowed mattress, her hands resting one upon the other near her head. She is simply attired in a frock, below which her naked feet are carelessly placed one over the other, the whole position suggesting that in the restlessness of pain she had just turned to find a cooler and easier place of rest.

Her portrait was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, her name appearing in his “Book of Sitters” in July 1788, when she was just over three years of age, and is one of the most famous child-pictures by that great master. The picture shows Little Penelope in a white dress and a dark belt, sitting on a stone sill, with trees in the background. Her mittened hands are folded in her lap, and her eyes are demurely cast down. She is wearing a high mob-cap, said to have belonged to Sir Joshua’s grandmother.

This picture was sold in 1859 to the Earl of Dudley for 1,100 guineas, and afterwards exhibited at Burlington House, when it was bought by Mr. David Thwaites for £20,060.

The model for the famous picture “Cherry Ripe,” painted by Sir John Everett-Millais, was Miss Talmage, who had appeared as Little Penelope at a fancy-dress ball, and it was said in later years that if there had been no Penelope Boothby by Sir Joshua Reynolds, there would have been no “Cherry Ripe” by Sir John Everett-Millais.

Sir Francis Chantrey, the great sculptor, also visited Ashbourne Church. His patron, Mrs. Robinson, when she gave him the order to execute that exquisite work, the Sleeping Children, in Lichfield Cathedral, expressly stipulated that he must see the figure of Penelope Boothby in Ashbourne Church before he began her work. Accordingly Chantrey came down to the church and completed his sketch afterwards at the “Green Man Inn,” working at it until one o’clock the next morning, when he departed by the London coach.

Ashbourne is one of the few places which kept up the football match on Shrove Tuesday, a relic probably of the past, when the ball was a creature or a human being, and life or death the object of the game. But now the game was to play a stuffed case or the biggest part of it up and down the stream, the Ecclesbourne, until the mill at either limit of the town was reached.

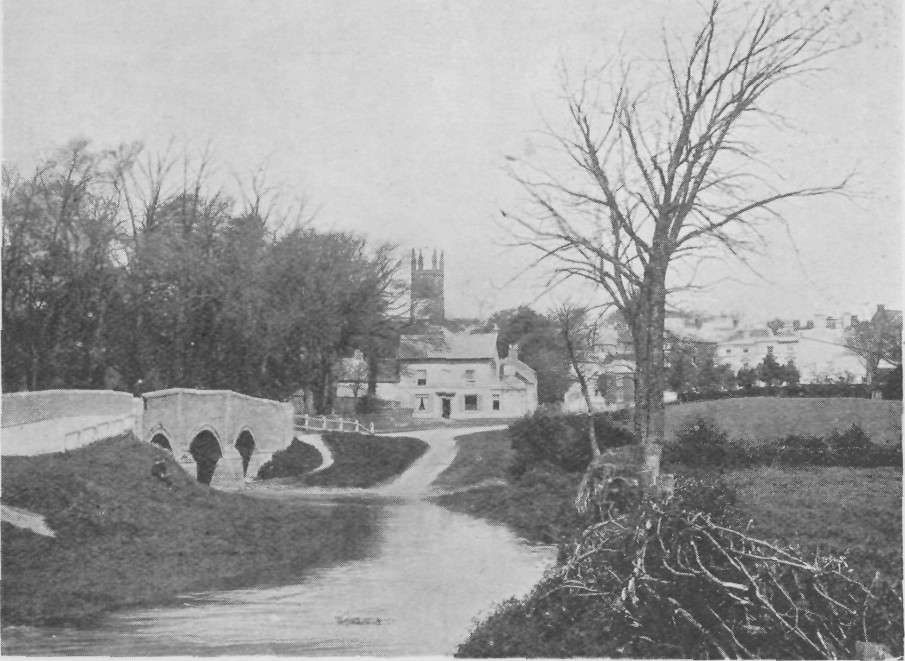

The River Dove, of which it has been written the “Dove’s flood is worth a king’s good,” formed the boundary between Derbyshire and Staffordshire, which we crossed by a bridge about two miles after leaving Ashbourne. This bridge, we were told, was known as the Hanging Bridge, because at one time people were hanged on the tree which stood on the border between the two counties, and we might have fared badly if our journey had been made in the good old times, when “tramps” were severely treated. Across the river lay the village of Mayneld, where the landlord of the inn was killed in a quarrel with Prince Charlie’s men in their retreat from Derby for resisting their demands, and higher up the country a farmer had been killed because he declined to give up his horse. They were not nearly so orderly as they retreated towards the north, for they cleared both provisions and valuables from the country on both sides of the roads. A cottage at Mayneld was pointed out to us as having once upon a time been inhabited by Thomas, or Tom Moore, Ireland’s great poet, whose popularity was as great in England as in his native country, and who died in 1852 at the age of seventy-three years. The cottage was at that time surrounded by woods and fields, and no doubt the sound of Ashbourne Church bells, as it floated in the air, suggested to him one of his sweetest and saddest songs:

Those evening bells! those evening bells,

How many a tale their music tells

Of youth and home and that sweet time

When last I heard their soothing chime.

Those joyous hours are passed away,

And many a heart that then was gay

Within the tomb now darkly dwells,

And hears no more those evening bells.

And so ’twill be when I am gone:

The tuneful peal will still ring on:

While other bards shall walk these dells

And sing your praise, sweet evening bells.

We passed Calwick Abbey, once a religious house, but centuries ago converted into a private mansion, which in the time of Handel (1685-1759) was inhabited by the Granville family. Handel, although a German, spent most of his time in England, and was often the guest of the nobility. It was said that it was at Calwick Abbey that his greatest oratorios were conceived, and that the organ on which he played was still preserved. We ourselves had seen an organ in an Old Hall in Cheshire on which he had played when a visitor there, and where was also shown a score copy in his own handwriting. All that was mortal of Handel was buried in Westminster Abbey, but his magnificent oratorios will endure to the end of time.

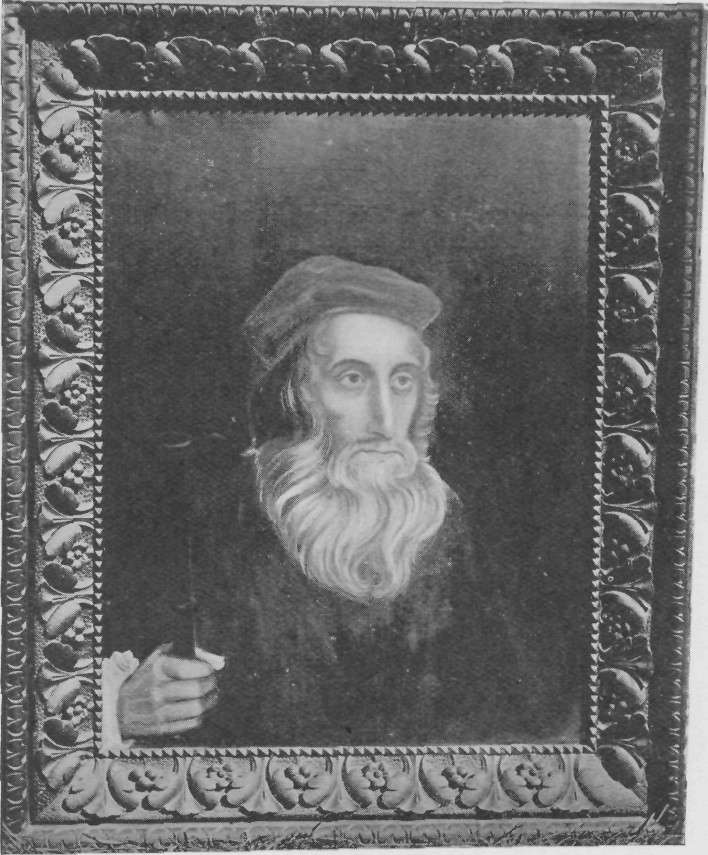

On arrival at Ellastone we left our luggage at the substantially built inn there while we went to visit Norbury Church, which was well worth seeing, and as my foot had now greatly improved we were able to get over the ground rather more quickly. Norbury was granted to the Fitzherberts in 1125, and, strange as it may appear, the original deed was still in the possession of that ancient family, whose chief residence was now at Swynnerton at the opposite side of Staffordshire, where they succeeded the Swynnerton family as owners of the estate. The black image of that grim crusader Swynnerton of Swynnerton still remained in the old chapel there, and as usual in ancient times, where the churches were built of sandstone, they sharpened their arrows on the walls or porches of the church, the holes made in sharpening them being plainly visible. Church restorations have caused these holes to be filled with cement in many places, like the bullet holes of the more recent period of the Civil War, but holes in the exact shape of arrow heads were still to be seen in the walls at Swynnerton, the different heights showing some of the archers to have been very tall men. In spite of severe persecution at the time of the Reformation this branch of the family of the Fitzherberts adhered to the Roman Catholic Faith, Sir Thomas Fitzherbert being one of the most prominent victims of the Elizabethan persecutions, having passed no less than thirty years of his life in various prisons in England.

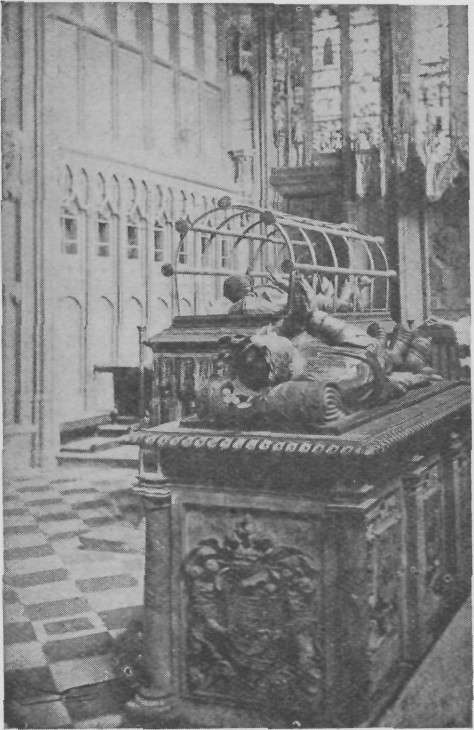

Norbury church was not a large one, but the chancel was nearly as large as the nave. It dated back to the middle of the fourteenth century, when Henry of Kniveton was rector, who made the church famous by placing a number of fine stained-glass windows in the chancel. The glass in these windows was very chaste and beautiful, owing to the finely tinted soft browns and greens, now probably mellowed by age, and said to rank amongst the finest of their kind in England. The grand monuments to the Fitzherberts were magnificently fine examples of the art and clothing of the past ages, the two most gorgeous tombs being those of the tenth and eleventh lords, in all the grandeur of plate armour, collars, decorations, spurs, and swords; one had an angel and the other a monk to hold his foot as he crossed into the unknown. The figures of their families as sculptured below them were also very fine. Considering that one of the lords had seventeen children and the other fifteen it was scarcely to be wondered at that descendants of the great family still existed.

Sir Nicholas, who died in 1473, occupied the first tomb, his son the second, and his children were represented dressed in the different costumes of their chosen professions, the first being in armour with a cross, and the next as a lawyer with a scroll, while another was represented as a monk with a book, but as the next had his head knocked off it was impossible to decipher him; others seemed to have gone into businesses of one kind or another.

The oldest monument in the church was a stone cross-legged effigy of a warrior in armour, dating from about the year 1300; while the plainest was the image of a female corpse in a shroud, on a gravestone, who was named … Elysebeth …

The which decessed the yeare that is goone,

A thousand four hundred neynty and oone.

The church was dedicated to St. Barloke, probably one of the ancient British Divines.

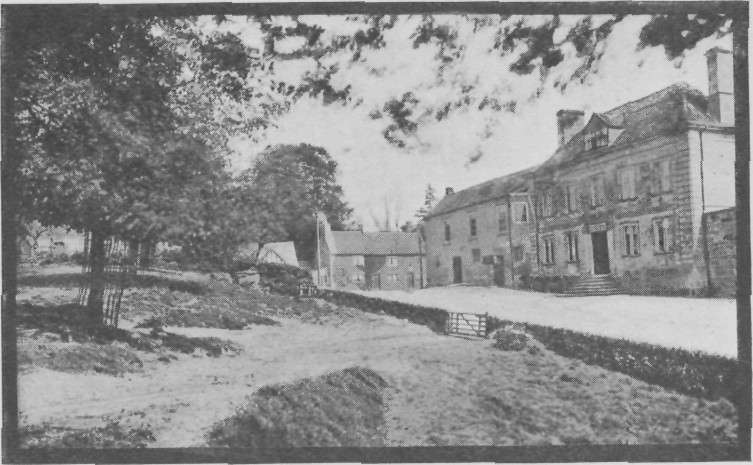

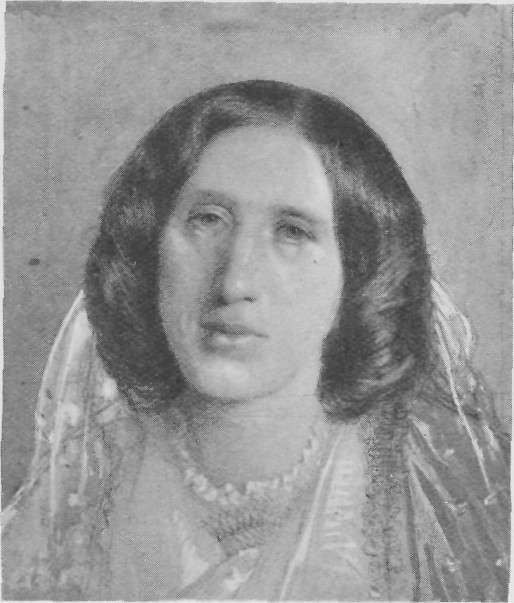

On returning to Ellastone we learned that the inn was associated with “George Eliot,” whose works we had heard of but had not read. We were under the impression that the author was a man, and were therefore surprised to find that “George Eliot” was only the nom de plume of a lady whose name was Marian Evans. Her grandfather was the village wheelwright and blacksmith at Ellastone, and the prototype of “Adam Bede” in her famous novel of that name.

GEORGE ELLIOT’S “DONNITHORPE ARMS,” ELLASTONE.

It has been said that no one has ever drawn a landscape more graphically than Marian Evans, and the names of places are so thinly veiled that if we had read the book we could easily have traced the country covered by “Adam Bede.” Thus Staffordshire is described as Loamshire, Derbyshire as Stoneyshire, and the Mountains of the Peak as the barren hills, while Oakbourne stands for Ashbourne, Norbourne for Norbury, and Hayslope, described so clearly in the second chapter of Adam Bede, is Ellastone, the “Donnithorpe Arms” being the “Bromley Arms Hotel,” where we stayed for refreshments. It was there that a traveller is described in the novel as riding up to the hotel, and the landlord telling him that there was to be a “Methodis’ Preaching” that evening on the village green, and the traveller stayed to listen to the address of “Dinah Morris,” who was Elizabeth Evans, the mother of the authoress.

Wootton Hall, which stands immediately behind the village of Ellastone, was at one time inhabited by Jean Jacques Rousseau, the great French writer, who, when he was expelled from France, took the Hall for twelve months in 1776, beginning to write there his Confessions, as well as his Letters on Botany, at a spot known as the “Twenty oaks.” It was very bad weather for a part of the time, and snowed incessantly, with a bitterly cold wind, but he wrote, “In spite of all, I would rather live in the hole of one of the rabbits of this warren, than in the finest rooms in London.”

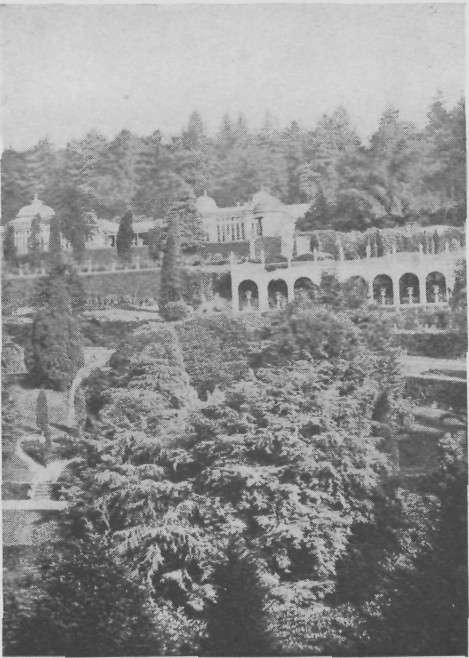

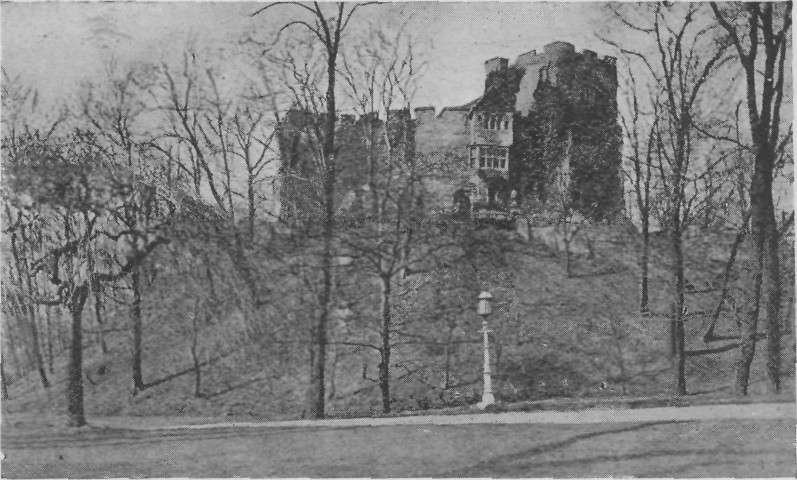

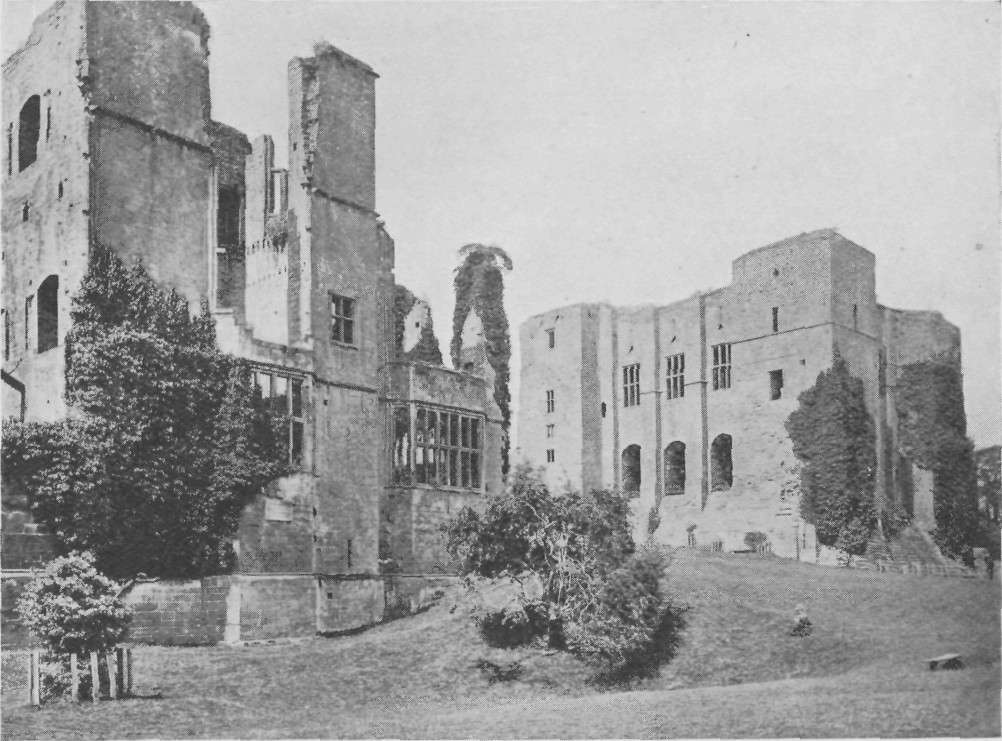

We now hurried across the country, along old country lanes and over fields, to visit Alton Towers; but, as it was unfortunately closed on that day, it was only by trespassing that we were able to see a part of the grounds. We could see the fine conservatories, with their richly gilded domes, and some portion of the ground and gardens, which were in a deep dell. These were begun by Richard, Earl of Shrewsbury, in the year 1814, who, after years of labour, and at enormous expense, converted them from a wilderness into one of the most extraordinary gardens in Europe, almost baffling description. There was a monument either to himself or the gardener, on which were the words:

He made the desert smile.

From the Uttoxeter Road we could see a Gothic bridge, with an embankment leading up to it, and a huge imitation of Stonehenge, in which we were much interested, that being one of the great objects of interest we intended visiting when we reached Salisbury Plain. We were able to obtain a small guide-book, but it only gave us the information that the gardens consisted of a “labyrinth of terraces, walls, trellis-work, arbours, vases, stairs, pavements, temples, pagodas, gates, parterres, gravel and grass walks, ornamental buildings, bridges, porticos, seats, caves, flower-baskets, waterfalls, rocks, cottages, trees, shrubs and beds of flowers, ivied walls, moss houses, rock, shell, and root work, old trunks of trees, etc., etc.,” so, as it would occupy half a day to see the gardens thoroughly, we decided to come again on some future occasion. A Gothic temple stood on the summit of a natural rock, and among other curiosities were a corkscrew fountain of very peculiar character, and vases and statues almost without end.

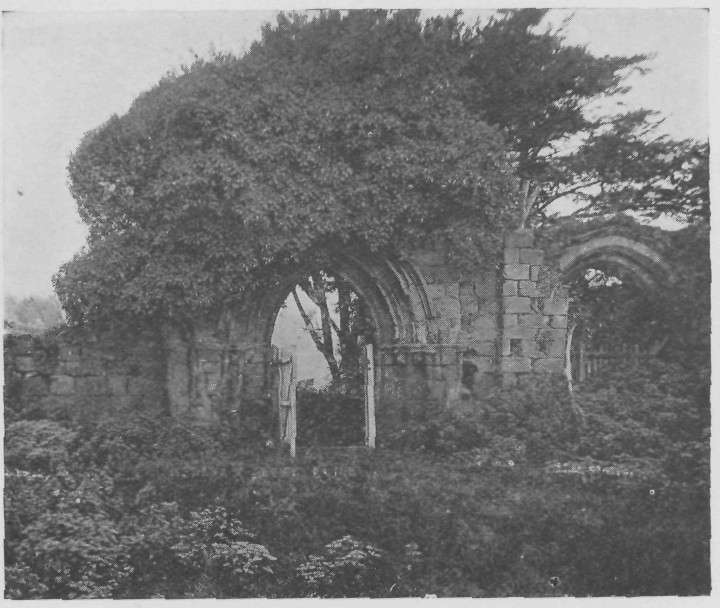

We now followed the main road to the Staffordshire town of Uttoxeter, passing the ruins of Croxden Abbey in the distance, where the heart of King John had been buried, and where plenty of traces of the extreme skill in agriculture possessed by the monks can be seen. One side of the chapel still served as a cowshed, but perhaps the most interesting features were the stone coffins in the orchard as originally placed, with openings so small, that a boy of ten can hardly lie in one.

But we missed a sight which as good churchmen we were afterwards told we ought to have remembered. October 31st was All-Hallows Eve, “when ghosts do walk,” and here we were in a place they revelled in—so much so that they gave their name to it, Duninius’ Dale. Here the curious sights known as “Will-o’-the-Wisp” could be seen magnificently by those who would venture a midnight visit. But we had forgotten the day.

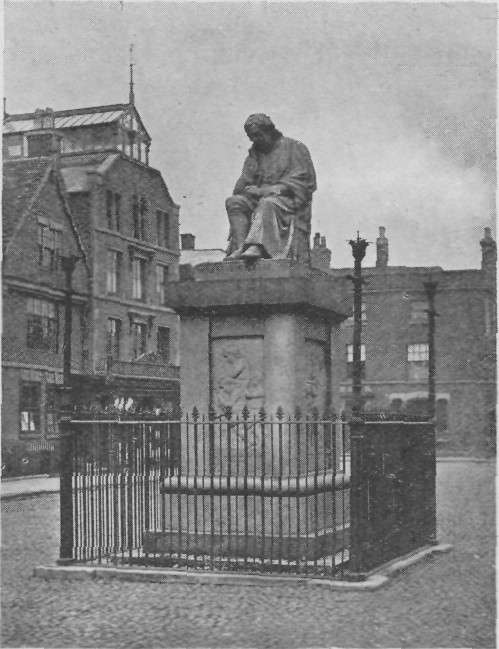

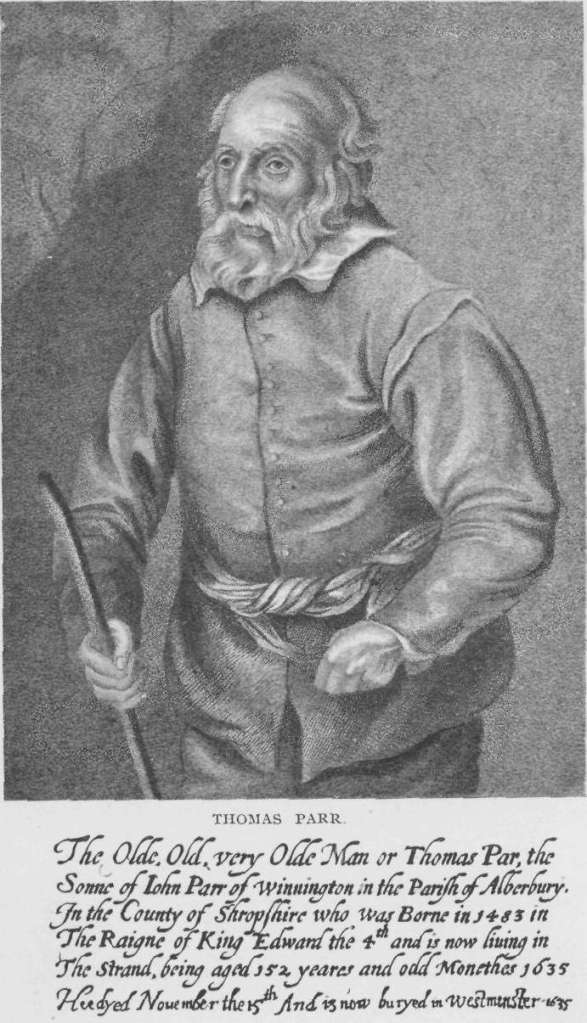

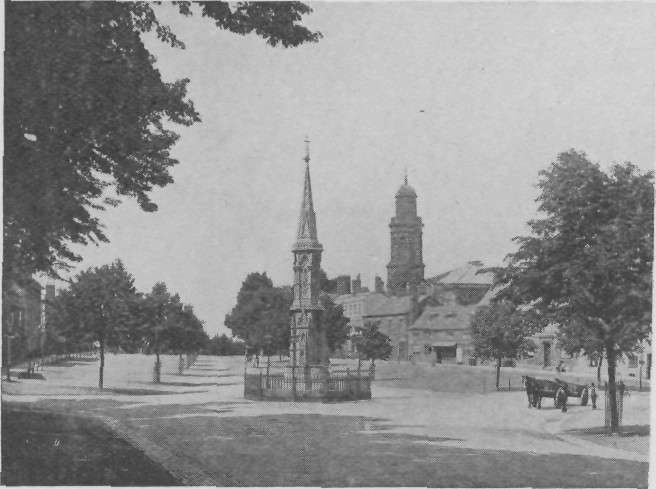

We stopped for tea at Uttoxeter, and formed the opinion that it was a clean but rather sleepy town. There was little to be seen in the church, as it was used in the seventeenth century as a prison for Scottish troops, “who did great damage.” It must, however, have been a very healthy town, if we might judge from the longevity of the notables who were born there: Sir Thomas Degge, judge of Western Wales and a famous antiquary, was born here in 1612, and died aged ninety-two; Thomas Allen, a distinguished mathematician and philosopher, the founder of the college at Dulwich and the local Grammar School as well, born 1542, died aged ninety; Samuel Bentley, poet, born 1720, died aged eighty-three; Admiral Alan Gardner, born at the Manor House in 1742, and who, for distinguished services against the French, was raised to the Irish Peerage as Baron Gardner of Uttoxeter, and was M.P. for Plymouth, died aged sixty-seven; Mary Howitt, the well-known authoress, born 1799, also lived to the age of eighty-nine. A fair record for a small country town! John Wesley preached in the marketplace, in the centre of which was a fountain erected to the memory of Dr. Samuel Johnson, the distinguished lexicographer. His father, whose home was at Lichfield, was a bookseller and had a bookstall in Uttoxeter Market, which he attended on market days. The story is told that on one occasion, not feeling very well, he asked his son, Samuel, to take his place, who from motives of pride flatly refused to do so. From this illness the old man never recovered, and many years afterwards, on the anniversary of that sorrowful day, Dr. Samuel Johnson, then in the height of his fame, came to the very spot in the market-place where this unpleasant incident occurred and did penance, standing bareheaded for a full hour in a pitiless storm of wind and rain, much to the surprise of the people who saw him.

We now bade good-bye to the River Dove, leaving it to carry its share of the Pennine Range waters to the Trent, and walked up the hill leading out of the town towards Abbots Bromley. We soon reached a lonely and densely wooded country with Bagot’s Wood to the left, containing trees of enormous age and size, remnants of the original forest of Needwood, while to the right was Chartley Park, embracing about a thousand acres of land enclosed from the same forest by the Earl of Derby, about the year 1248. In this park was still to be seen the famous herd of wild cattle, whose ancestors were known to have been driven into the park when it was enclosed. These animals resisted being handled by men, and arranged themselves in a semi-circle on the approach of an intruder. The cattle were perfectly white, excepting their extremities, their ears, muzzles, and hoofs being black, and their long spreading horns were also tipped with black. Chartley was granted by William Rufus to Hugh Lupus, first Earl of Chester, whose descendant, Ranulph, a Crusader, on his return from the Holy War, built Beeston Castle in Cheshire, with protecting walls and towers, after the model of those at Constantinople. He also built the Castle at Chartley about the same period, A.D. 1220, remarkable as having been the last place of imprisonment for the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots, as she was taken from there in 1586 to be executed at Fotheringhay.

We were interested in these stories of Chartley Castle, for in our own county cattle with almost the same characteristics were preserved in the Parks of Lyme and Somerford, and probably possessed a similar history. That Ranulph was well known can be assumed from the fact that Langland in his Piers Plowman in the fourteenth century says:

I cannot perfitly my paternoster as the Priest it singeth.

But I can rhymes of Robin Hood and Randall Erie of Chester.

Queer company, and yet it was an old story that Robin did find an asylum at Chartley Castle.

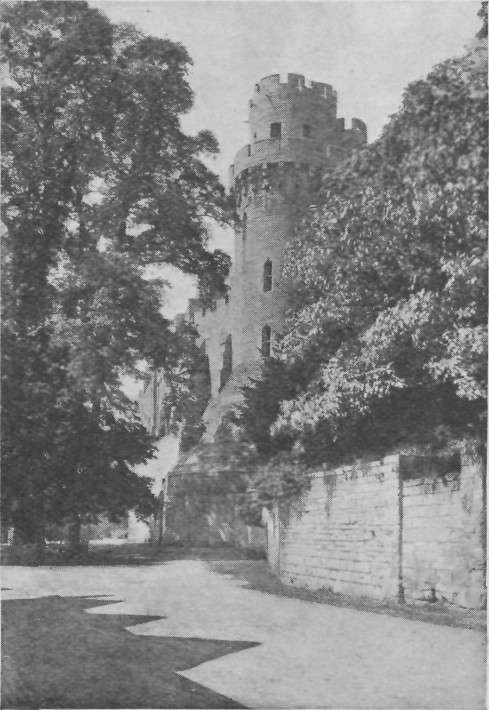

THE HORN DANCERS, ABBOTS BROMLEY.

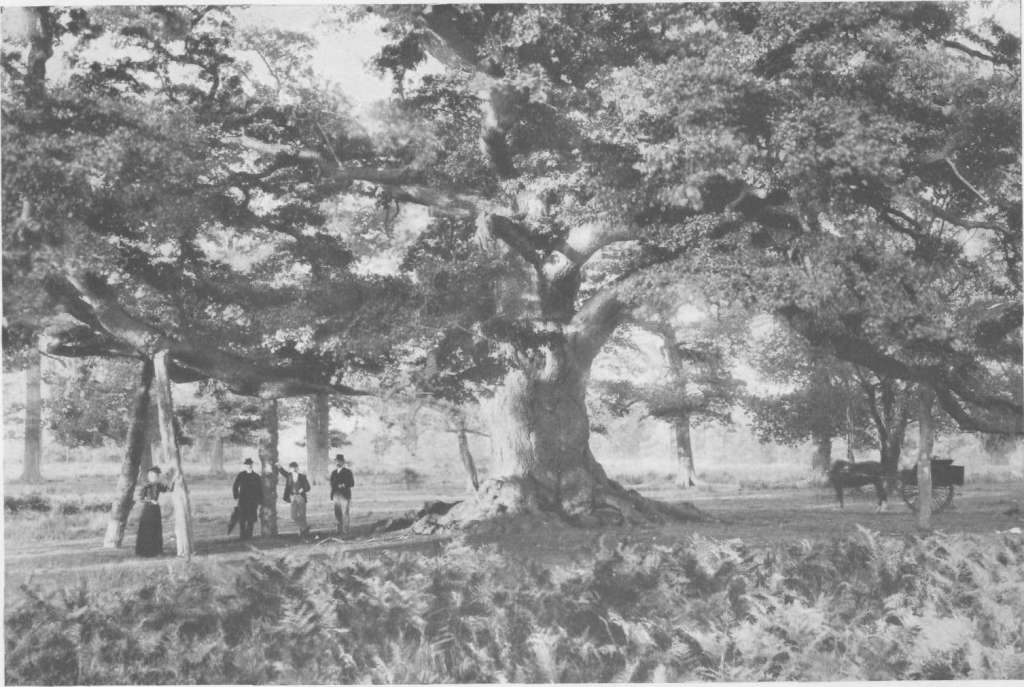

We overtook an elderly man on the road returning home from his day’s toil on the Bagot estate, and he told us of an old oak tree of tremendous size called the “Beggar’s Oak”; but it was now too dark for us to see it. The steward of the estate had marked it, together with others, to be felled and sold; but though his lordship was very poor, he would not have the big oak cut down. He said that both Dick Turpin and Robin Hood had haunted these woods, and when he was a lad a good many horses were stolen and hidden in lonely places amongst the thick bushes to be sold afterwards in other parts of the country.

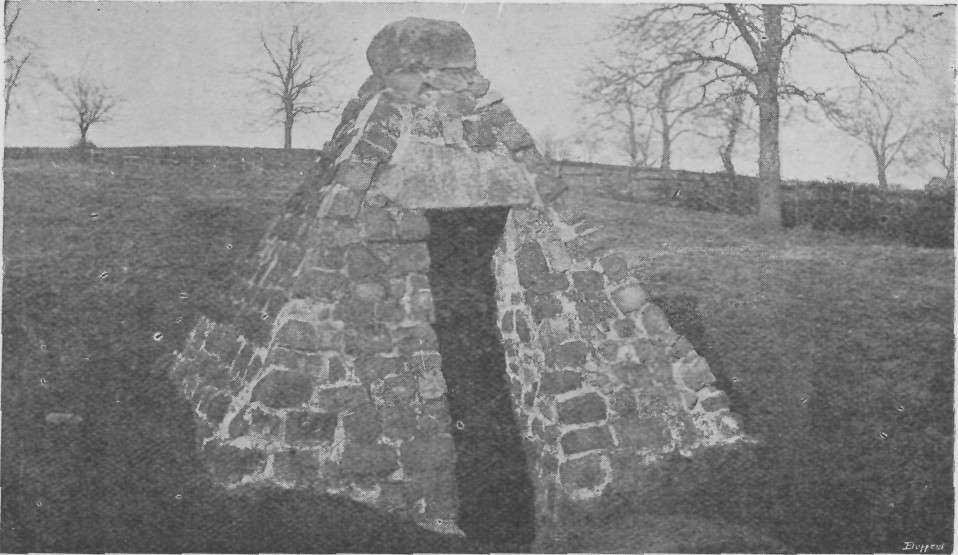

The “Beggar’s Oak” was mentioned in the History of Staffordshire in 1830, when its branches were measured by Dr. Darwen as spreading 48 feet in every direction. There was also a larger oak mentioned with a trunk 21 feet 4-1/2 inches in circumference, but in a decayed condition. This was named the Swilcar Lawn Oak, and stood on the Crown lands at Marchington Woodlands, and in Bagot’s wood were also the Squitch, King, and Lord Bagot’s Walking stick, all fine trees. There were also two famous oaks at Mavesyn Ridware called “Gog and Magog,” but only their huge decayed trunks remained. Abbots Bromley had some curious privileges, and some of the great games were kept up. Thus the heads of the horses and reindeers for the “hobby horse” games were to be seen at the church.

The owner of this region, Lord Bagot, could trace his ancestry back to before the Conquest, for the Normans found one Bagod in possession. In course of time, when the estate had become comparatively poor, we heard that the noble owner had married the daughter of Mr. Bass, the rich brewer of Burton, the first of the Peerage marriages with the families of the new but rich.

We passed the Butter Cross and the old inn, reminiscent of stage-coach days, as the church bell was tolling, probably the curfew, and long after darkness had set in, for we were trying to reach Lichfield, we came to the village of Handsacre, where at the “Crown Inn” we stayed the night.

(Distance walked twenty-five miles.)

Wednesday, November 1st.

Although the “Crown” at Handsacre was only a small inn, we were very comfortable, and the company assembled on the premises the previous evening took a great interest in our travels. We had no difficulty in getting an early breakfast, and a good one too, before leaving the inn this morning, but we found we had missed seeing one or two interesting places which we passed the previous night in the dark, and we had also crossed the River Trent as it flowed towards the great brewery town of Burton, only a few miles distant.

WHERE OFFA’S DYKE CROSSES THE MAIS ROAD.

Daylight found us at the foot of the famous Cannock Chase. The Chase covered about 30,000 acres of land, which had been purposely kept out of cultivation in olden times in order to form a happy hunting-ground for the Mercian Kings, who for 300 years ruled over that part of the country. The best known of these kings was Offa, who in the year 757 had either made or repaired the dyke that separated England from Wales, beginning at Chepstow in Monmouthshire, and continuing across the country into Flintshire. It was not a dyke filled with water, as for the most part it passed over a very hilly country where water was not available, but a deep trench sunk on the Welsh side, the soil being thrown up on the English side, forming a bank about four yards high, of which considerable portions were still visible, and known as “Offa’s Dyke.” Cannock Chase, which covered the elevations to our right, was still an ideal hunting-country, as its surface was hilly and diversified, and a combination of moorland and forest, while the mansions of the noblemen who patronised the “Hunt” surrounded it on all sides, that named “Beau-Desert,” the hall or hunting-box of the Marquis of Anglesey, being quite near to our road.

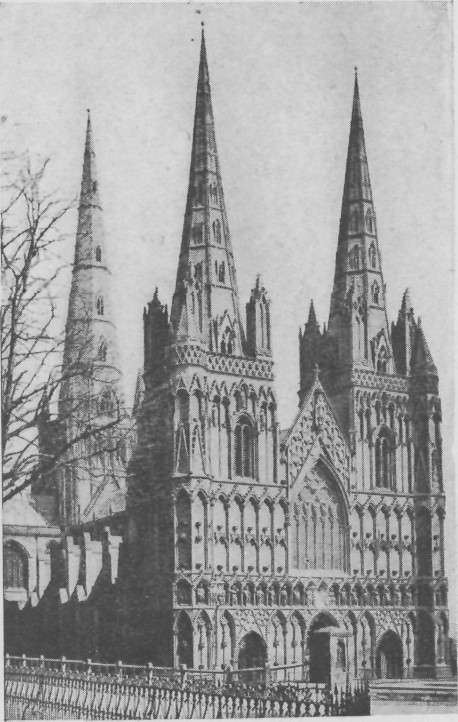

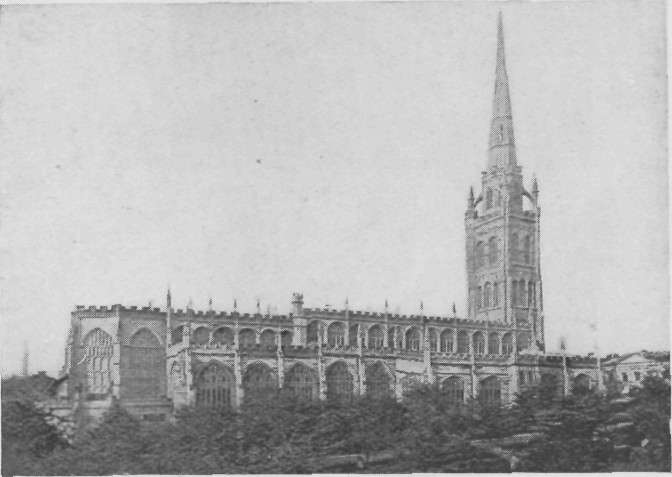

We soon arrived at Lichfield, and on entering the town the three lofty and ornamental spires of the cathedral, which from their smart appearance were known as “The Three Ladies,” immediately attracted our attention. But for these, travellers entering Lichfield by this road might easily have passed the cathedral without noticing it, as it stands on low and rather swampy ground, where its fine proportions do not show to advantage.

The Close of the cathedral, which partially surrounded it, was heavily fortified in the time of the Civil War, causing the cathedral to be very badly damaged, for it suffered no less than three different sieges by the armies of the Parliament.

The cathedral was dedicated to St. Chad, but whether he was the same St. Chad whose cave was in the rocky bank of the River Don, and about whom we had heard farther north, or not, we could not ascertain. He must have been a water-loving saint, as a well in the town formed by a spring of pure water was known as St. Chad’s Well, in which the saint stood naked while he prayed, upon a stone which had been preserved by building it into the wall of the well. There was also in the cathedral at one time the “Chapel of St. Chad’s Head,” but this had been almost destroyed during the first siege of 1643. The ancient writings of the patron saint in the early Welsh language had fortunately been preserved. Written on parchment and ornamented with rude drawings of the Apostles and others, they were known as St. Chad’s Gospels, forming one of the most treasured relics belonging to the cathedral, but, sad to relate, had been removed by stealth, it was said, from the Cathedral of Llandaff.

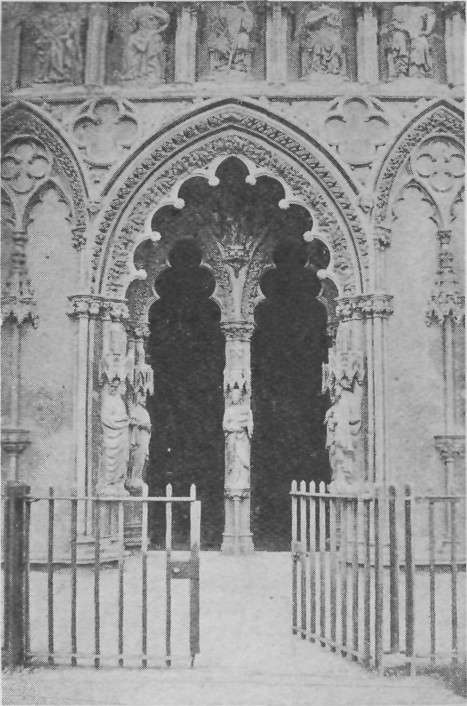

The first siege began on March 2nd, 1643, which happened to be St. Chad’s Day, and it was recorded that during that siege “Lord Brooke who was standing in the street was killed, being shot through the eye by Dumb Dyott from the cathedral steeple.” The cathedral was afterwards used by Cromwell’s men as a stable, and every ornament inside and outside that they could reach was greatly damaged; but they appeared to have tried to finish the cathedral off altogether, when in 1651 they stripped the lead from the roof and then set the woodwork on fire. It was afterwards repaired and rebuilt, but nearly all the ornaments on the west front, which had been profusely decorated with the figures of martyrs, apostles, priests, and kings, had been damaged or destroyed. At the Restoration an effort was made to replace these in cement, but this proved a failure, and the only perfect figure that remained then on the west front was a rather clumsy one of Charles II, who had given a hundred timber trees out of Needwood Forest to repair the buildings. Many of the damaged figures were taken down in 1744, and some others were removed later by the Dean, who was afraid they might fall on his head as he went in and out of the cathedral.

In those days chimney sweepers employed a boy to climb up the inside of the chimneys and sweep the parts that could not be reached with their brush from below, the method of screwing one stale to the end of another and reaching the top in that way being then unknown. These boys were often cruelly treated, and had even been known to be suffocated in the chimney. The nature of their occupation rendered them very daring, and for this reason the Dean employed one of them to remove the rest of the damaged figures, a service which he satisfactorily performed at no small risk both to himself and others.

There is a very fine view in the interior of the cathedral looking from west to east, which extends to a distance of 370 feet, and of which Sir Gilbert Scott, the great ecclesiastical architect, who was born in 1811, has written, “I always hold this work to be almost absolute perfection in design and detail”; another great authority said that when he saw it his impressions were like those described by John Milton in his “Il Penseroso”:

Let my due feet never fail

To walk the studious cloisters pale,

And love the high embossed roof,

With antique pillars massy proof,

And storied windows richly dight,

Casting a dim, religious light:

There let the pealing organ blow,

To the full-voiced quire below.

In service high, and anthems clear,

As may with sweetness, through mine ear,

Dissolve me into ecstacies.

And bring all heaven before mine eyes.

We had not much time to explore the interior, but were obliged to visit the white marble effigy by the famous Chantrey of the “Sleeping Children” of Prebendary Robinson. It was beautifully executed, but for some reason we preferred that of little Penelope we had seen the day before, possibly because these children appeared so much older and more like young ladies compared with Penelope, who was really a child. Another monument by Chantrey which impressed us more strongly than that of the children was that of Bishop Ryder in a kneeling posture, which we thought a very fine production. There was also a slab to the memory of Admiral Parker, the last survivor of Nelson’s captains, and some fine stained-glass windows of the sixteenth century formerly belonging to the Abbey of Herckrode, near Liège, which Sir Brooke Boothby, the father of little Penelope, had bought in Belgium in 1803 and presented to the cathedral.

The present bishop, Bishop Selwyn, seemed to be very much loved, as everybody had a good word for him. One gentleman told us he was the first bishop to reside at the palace, all former bishops having resided at Eccleshall, a town twenty-six miles away. Before coming to Lichfield he had been twenty-two years in New Zealand, being the first bishop of that colony. He died seven years after our visit, and had a great funeral, at which Mr. W.E. Gladstone, who described Selwyn as “a noble man,” was one of the pall-bearers. The poet Browning’s words were often applied to Bishop Selwyn:

We that have loved him so, followed and honour’d him,

Lived in his mild and magnificent eye,

Caught his clear accents, learnt his great language,

Made him our pattern to live and to die.