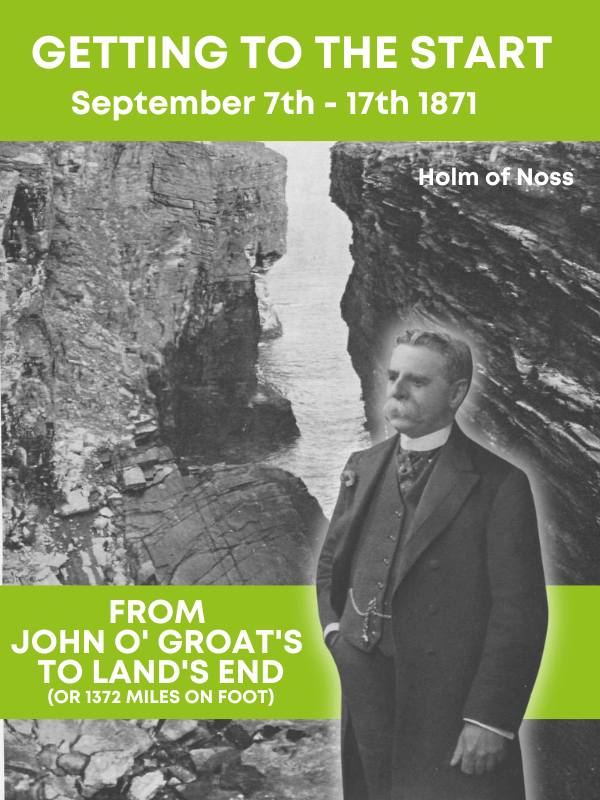

It took a week for the brothers to travel from Warrington to John O’ Groat’s to start the epic journey and this in itself was a big adventure! You can find all the other chapters here: John O Groats to Land’s End (or 1372 Miles on Foot)

FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) My Great Great Grandfather, John Naylor and his brother Robert where the first people to walk from From John O Groat’s to Lands End in 1871. Read the book in full for free here on http://www.nearlyuphill.co.uk in chapters or download their 660 page book here – FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) All words are written by them and all pictures are taken from the original book which was written in 1916 by John Naylor.

HOW WE GOT TO JOHN O’ GROAT’S

Sept. 7. Warrington to Glasgow by train—Arrived too late to catch the boat on the Caledonian Canal for Iverness—Trained to Aberdeen.

Sept. 8. A day in the “Granite City”—Boarded the s.s. St. Magnus intending to land at Wick—Decided to remain on board.

Sept. 9. Landed for a short time at Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands—During the night encountered a storm in the North Sea.

Sept. 10. (Sunday). Arrived at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands at 2 a.m.

Sept. 11. Visited Bressay Island and the Holm of Noss—Returned to St. Magnus at night.

Sept. 12. Landed again at Kirkwall—Explored Cathedral—Walked across the Mainland of the Orkneys to Stromness, visiting the underground house at Maeshowe and the Standing Stones at Stenness on our way.

Sept. 13. Visited the Quarries where Hugh Miller made his wonderful geological researches—Explored coast scenery, including the Black Craig.

Sept. 14. Crossed the Pentland Firth in a sloop—Unfavourable wind prevented us sailing past the Old Man of Hoy, so went by way of Lang Hope and Scrabster Roads, passing Dunnet Head on our way to Thurso, where we landed and stopped for the night.

Sept. 15. Travelled six miles by the Wick coach and walked the remaining fifteen miles to John o’ Groat’s—Lodged at the “Huna Inn.”

Sept. 16. Gathered some wonderful shells on the beach and explored coast scenery at Duncansbay.

Sept. 17. (Sunday). Visited a distant kirk with the landlord and his wife and listened to a wonderful sermon.

Thursday, September 7th.

It was one o’clock in the morning when we started on the three-mile walk to Warrington, where we were to join the 2.18 a.m. train for Glasgow, and it was nearly ten o’clock when we reached that town, the train being one hour and twenty minutes late. This delay caused us to be too late for the steamboat by which we intended to continue our journey further north, and we were greatly disappointed in having thus early in our journey to abandon the pleasant and interesting sail down the River Clyde and on through the Caledonian Canal. We were, therefore, compelled to alter our route, so we adjourned to the Victoria Temperance Hotel for breakfast, where we were advised to travel to Aberdeen by train, and thence by steamboat to Wick, the nearest available point to John o’ Groat’s.

We had just time to inspect Sir Walter Scott’s monument that adorned the Square at Glasgow, and then we left by the 12.35 train for Aberdeen. It was a long journey, and it was half-past eight o’clock at night before we reached our destination, but the weariness of travelling had been whiled away by pleasant company and delightful scenery.

We had travelled continuously for about 360 miles, and we were both sleepy and tired as we entered Forsyth’s Hotel to stay the night.

Friday, September 8th.

After a good night’s rest, followed by a good breakfast, we went out to inquire the time our boat would leave, and, finding it was not due away until evening, we returned to the hotel and refreshed ourselves with a bath, and then went for a walk to see the town of Aberdeen, which is mostly built of the famous Aberdeen granite. The citizens were quite proud of their Union Street, the main thoroughfare, as well they might be, for though at first sight we thought it had rather a sombre appearance, yet when the sky cleared and the sun shone out on the golden letters that adorned the buildings we altered our opinion, for then we saw the “Granite City” at its best.

We spent the time rambling along the beach, and, as pleasure seekers generally do, passed the day comfortably, looking at anything and everything that came in our way. By no means sea-faring men, having mainly been accustomed to village life, we had some misgivings when we boarded the s.s. St. Magnus at eight o’clock in the evening, and our sensations during the night were such as are common to what the sailors call “land-lubbers.” We were fortunate, however, in forming the acquaintance of a lively young Scot, who was also bound for Wick, and who cheered us during the night by giving us copious selections from Scotland’s favourite bard, of whom he was greatly enamoured. We heard more of “Rabbie Burns” that night than we had ever heard before, for our friend seemed able to recite his poetry by the yard and to sing some of it also, and he kept us awake by occasionally asking us to join in the choruses. Some of the sentiments of Burns expressed ideals that seem a long time in being realised, and one of his favourite quotations, repeated several times by our friend, dwells in our memory after many years:

For a’ that an’ a’ that

It’s coming, yet, for a’ that,

That man to man the war-ld o’er

Shall brithers be for a’ that.

During the night, as the St. Magnus ploughed her way through the foaming billows, we noticed long, shining streaks on the surface of the water, varying in colour from a fiery red to a silvery white, the effect of which, was quite beautiful. Our friend informed us these were caused by the stampede of the shoals of herrings through which we were then passing.

The herring fishery season was now on, and, though we could not distinguish either the fishermen or their boats when we passed near one of their fishing-grounds, we could see the lights they carried dotted all over the sea, and we were apprehensive lest we should collide with some of them, but the course of the St. Magnus had evidently been known and provided for by the fishermen.

We had a long talk with our friend about our journey north, and, as he knew the country well, he was able to give us some useful information and advice. He told us that if we left the boat at Wick and walked to John o’ Groat’s from there, we should have to walk the same way back, as there was only the one road, and if we wished to avoid going over the same ground twice, he would advise us to remain on the St. Magnus until she reached her destination, Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands, and the cost by the boat would be very little more than to Wick. She would only stay a short time at Lerwick, and then we could return in her to Kirkwall, in the Orkney Islands. From that place we could walk across the Mainland to Stromness, where we should find a small steamboat which conveyed mails and passengers across the Pentland Firth to Thurso in the north of Scotland, from which point John o’ Groat’s could easily be reached, and, besides, we might never again have such a favourable opportunity of seeing the fine rock scenery of those northern islands.

From a photograph taken in 1867.

We were delighted with his suggestion, and wrote a hurried letter home advising our people there of this addition to our journey, and our friend volunteered to post the letter for us at Wick. It was about six o’clock in the morning when we neared that important fishery town and anchored in the harbour, where we had to stay an hour or two to load and unload cargo. Our friend the Scot had to leave us here, but we could not allow him to depart without some kind of ceremony or other, and as the small boat came in sight that was to carry him ashore, we decided to sing a verse or two of “Auld Lang Syne” from his favourite poet Burns; but my brother could not understand some of the words in one of the verses, so he altered and anglicised them slightly:

An’ here’s a haund, my trusty friend,

An’ gie’s a haund o’ thine;

We’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet,

For the sake o’ auld lang syne.

Some of the other passengers joined in the singing, but we never realised the full force of this verse until we heard it sung in its original form by a party of Scots, who, when they came to this particular verse, suited the action to the word by suddenly taking hold of each other’s hands, thereby forming a cross, and meanwhile beating time to the music. Whether the cross so formed had any religious significance or not, we did not know.

Our friend was a finely built and intelligent young man, and it was with feelings of great regret that we bade him farewell and watched his departure over the great waves, with the rather mournful presentiment that we were being parted from him for ever!

Saturday, September 9th.

There were signs of a change in the weather as we left Wick, and the St. Magnus rolled considerably; but occasionally we had a good view of the precipitous rocks that lined the coast, many of them having been christened by the sailors after the objects they represented, as seen from the sea. The most prominent of these was a double-headed peak in Caithness, which formed a remarkably perfect resemblance to the breasts of a female giant with nipples complete, and this they had named the “Maiden’s Paps.” Then there was the “Old Man of Hoy,” and other rocks that stood near the entrance to that terrible torrent of the sea, the Pentland Firth; but, owing to the rolling of our ship, we were not in a fit state either of mind or body to take much interest in them, and we were very glad when we reached the shelter of the Orkney Islands and entered the fine harbour of Kirkwall. Here we had to stay for a short time, so we went ashore and obtained a substantial lunch at the Temperance Hotel near the old cathedral, wrote a few letters, and at 3 p.m. rejoined the St. Magnus.

The sea had been quite rough enough previously, but it soon became evident that it had been smooth compared with what followed, and during the coming night we wished many times that our feet were once more on terra firma. The rain descended, the wind increased in violence, and the waves rolled high and broke over the ship, and we were no longer allowed to occupy our favourite position on the upper deck, but had to descend a stage lower. We were saturated with water from head to foot in spite of our overalls, and we were also very sick, and, to add to our misery, we could hear, above the noise of the wind and waves, the fearful groaning of some poor woman who, a sailor told us, had been suddenly taken ill, and it was doubtful if she could recover. He carried a fish in his hand which he had caught as it was washed on deck, and he invited us to come and see the place where he had to sleep. A dismal place it was too, flooded with water, and not a dry thing for him to put on. We could not help feeling sorry that these sailors had such hardships to undergo; but he seemed to take it as a matter of course, and appeared to be more interested in the fish he carried than in the storm that was then raging. We were obliged to keep on the move to prevent our taking cold, and we realised that we were in a dark, dismal, and dangerous position, and thought of the words of a well-known song and how appropriate they were to that occasion:

“O Pilot! ’tis a fearful night,

There’s danger on the deep;

I’ll come and pace the deck with thee,

I do not dare to sleep.”

“Go down!” the Pilot cried, “go down!

This is no place for thee;

Fear not! but trust in Providence,

Wherever thou may’st be.”

The storm continued for hours, and, as it gradually abated, our feelings became calmer, our fears subsided, and we again ventured on the upper deck. The night had been very dark hitherto, but we could now see the occasional glimmering of a light a long distance ahead, which proved to be that of a lighthouse, and presently we could distinguish the bold outlines of the Shetland Islands.

As we entered Bressay Sound, however, a beautiful transformation scene suddenly appeared, for the clouds vanished as if by magic, and the last quarter of the moon, surrounded by a host of stars, shone out brilliantly in the clear sky. It was a glorious sight, for we had never seen these heavenly bodies in such a clear atmosphere before, and it was hard to realise that they were so far away from us. We could appreciate the feelings of a little boy of our acquaintance, who, when carried outside the house one fine night by his father to see the moon, exclaimed in an ecstasy of delight: “Oh, reach it, daddy!—reach it!” and it certainly looked as if we could have reached it then, so very near did it appear to us.

It was two o’clock on Sunday morning, September 10th, when we reached Lerwick, the most northerly town in Her Majesty’s British Dominions, and we appealed to a respectable-looking passenger who was being rowed ashore with us in the boat as to where we could obtain good lodgings. He kindly volunteered to accompany us to a house at which he had himself stayed before taking up his permanent residence as a tradesman in the town and which he could thoroughly recommend. Lerwick seemed a weird-looking place in the moonlight, and we turned many corners on our way to our lodgings, and were beginning to wonder how we should find our way out again, when our companion stopped suddenly before a private boarding-house, the door of which was at once opened by the mistress. We thanked the gentleman for his kind introduction, and as we entered the house the lady explained that it was her custom to wait up for the arrival of the St. Magnus. We found the fire burning and the kettle boiling, and the cup that cheers was soon on the table with the usual accompaniments, which were quickly disposed of. We were then ushered to our apartments —a bedroom and sitting or dining-room combined, clean and comfortable, but everything seemed to be moving like the ship we had just left. Once in bed, however, we were soon claimed by the God of Slumber, sleep, and dreams—our old friend Morpheus.

Sunday, September 10th.

In the morning we attended the English Episcopalian Church, and, after service, which was rather of a high church character, we walked into the country until we came in sight of the rough square tower of Scalloway Castle, and on our return we inspected the ruins of a Pictish castle, the first of the kind we had seen, although we were destined to see many others in the course of our journey.

Commercial Street as it was in 1871.

The Picts, we were informed, were a race of people who settled in the north of Scotland in pre-Roman times, and who constructed their dwellings either of earth or stone, but always in a circular form. This old castle was built of stone, and the walls were five or six yards thick; inside these walls rooms had been made for the protection of the owners, while the circular, open space enclosed by the walls had probably been for the safe housing of their cattle. An additional protection had also been formed by the water with which the castle was surrounded, and which gave it the appearance of a small island in the middle of a lake. It was connected with the land by means of a narrow road, across which we walked. The castle did not strike us as having been a very desirable place of residence; the ruins had such a very dismal and deserted appearance that we did not stay there long, but returned to our lodgings for lunch. After this we rested awhile, and then joined the townspeople, who were patrolling every available space outside. The great majority of these were women, healthy and good-looking, and mostly dressed in black, as were also those we afterwards saw in the Orkneys and the extreme north of Scotland, and we thought that some of our disconsolate bachelor friends might have been able to find very desirable partners for life in these northern dominions of Her Majesty the Queen.

The houses in Lerwick had been built in all sorts of positions without any attempt at uniformity, and the rough, flagged passage which did duty for the main street was, to our mind, the greatest curiosity of all, and almost worth going all the way to Shetland to see. It was curved and angled in such an abrupt and zigzag manner that it gave us the impression that the houses had been built first, and the street, where practicable, filled in afterwards. A gentleman from London was loud in his praise of this wonderful street; he said he felt so much safer there than in “beastly London,” as he could stand for hours in that street before the shop windows without being run over by any cab, cart, or omnibus, and without feeling a solitary hand exploring his coat pockets. This was quite true, as we did not see any vehicles in Lerwick, nor could they have passed each other through the crooked streets had they been there, and thieves would have been equally difficult to find. Formerly, however, Lerwick had an evil reputation in that respect, as it was noted for being the abode of sheep-stealers and pirates, so much so, that, about the year 1700, it had become such a disreputable place that an earnest appeal was made to the “Higher Authorities” to have the place burnt, and for ever made desolate, on account of its great wickedness. Since that time, however, the softening influences of the Christian religion had permeated the hearts of the people, and, at the time of our visit, the town was well supplied with places of worship, and it would have been difficult to have found any thieves there then. We attended evening service in the Wesleyan Chapel, where we found a good congregation, a well-conducted service, and an acceptable preacher, and we reflected that Mr. Wesley himself would have rejoiced to know that even in such a remote place as Lerwick his principles were being promulgated.

Monday, September 11th.

We rose early with the object of seeing all we could in the short time at our disposal, which was limited to the space of a single day, or until the St. Magnus was due out in the evening on her return journey. We were anxious to see a large cavern known as the Orkneyman’s Cave, but as it could only be reached from the sea, we should have had to engage a boat to take us there. We were told the cave was about fifty feet square at the entrance, but immediately beyond it increased to double the size; it was possible indeed to sail into it with a boat and to lose sight of daylight altogether.

The story goes that many years ago an Orkneyman was pursued by a press-gang, but escaped being captured by sailing into the cave with his boat. He took refuge on one of the rocky ledges inside, but in his haste he forgot to secure his boat, and the ground swell of the sea washed it out of the cave. To make matters worse, a storm came on, and there he remained a prisoner in the cave for two days; but as soon as the storm abated he plunged into the water, swam to a small rock outside, and thence climbed to the top of the cliff and so escaped. Since that event it had been known as the Orkneyman’s Cave.

We went to the boat at the appointed time, but unfortunately the wind was too strong for us to get round to the cave, so we were disappointed. The boatman suggested as the next best thing that we should go to see the Island of Noss. He accordingly took us across the bay, which was about a mile wide, and landed us on the Island of Bressay. Here it was necessary for us to get a permit to enable us to proceed farther, so, securing his boat, the boatman accompanied us to the factor’s house, where he procured a pass, authorising us to land on the Island of Noss, of which the following is a facsimile:

Allow Mr. Nailer and friends

to land on Noss.

To Walter. A.M. Walker.

Here he left us, as we had to walk across the Island of Bressay, and, after a tramp of two or three miles, during which we did not see a single human being, we came to another water where there was a boat. Here we found Walter, and, after we had exhibited our pass, he rowed us across the narrow arm of the sea and landed us on the Island of Noss. He gave us careful instructions how to proceed so that we could see the Holm of Noss, and warned us against approaching too near the edge of the precipice which we should find there. After a walk of about a mile, all up hill, we came to the precipitous cliffs which formed the opposite boundary of the island, and from a promontory there we had a magnificent view of the rocks, with the waves of the sea dashing against them, hundreds of feet below. A small portion of the island was here separated from the remainder by a narrow abyss about fifty feet wide, down which it was terrible to look, and this separated portion was known as the Holm of Noss. It rose precipitously on all sides from the sea, and its level surface on the top formed a favourite nesting-place for myriads of wild birds of different varieties, which not only covered the top of the Holm, but also the narrow ledges along its jagged sides. Previous to the seventeenth century, this was one of the places where the foot of man had never trod, and a prize of a cow was offered to any man who would climb the face of the cliff and establish a connection with the mainland by means of a rope, as it was thought that the Holm would provide pasturage for about twenty sheep. A daring fowler, from Foula Island, successfully performed the feat, and ropes were firmly secured to the rocks on each side, and along two parallel ropes a box or basket was fixed, capable of holding a man and a sheep. This apparatus was named the Cradle of Noss, and was so arranged that an Islander with or without a sheep placed in the cradle could drag himself across the chasm in either direction. Instead, however, of returning by the rope or cradle, on which he would have been comparatively safe, the hardy fowler decided to go back by the same way he had come, and, missing his foothold, fell on the rocks in the sea below and was dashed to pieces, so that the prize was never claimed by him.

We felt almost spellbound as we approached this awful chasm, and as if we were being impelled by some invisible force towards the edge of the precipice. It fairly made us shudder as on hands and knees we peered down on the abysmal depths below. It was a horrible sensation, and one that sometimes haunted us in our dreams for years afterwards, and we felt greatly relieved when we found that we could safely crawl away and regain an upright posture. We could see thousands upon thousands of wild birds, amongst which the ordinary sea-gull was largely represented; but there were many other varieties of different colours, and the combination of their varied cries, mingled with the bleating of the sheep, the whistling of the wind, the roaring of the waves as they dashed against the rocks below, or entered the caverns with a sound like distant thunder, tended to make us feel quite bewildered. We retired to the highest elevation we could find, and there, 600 miles from home, and perhaps as many feet above sea-level, was solitude in earnest. We were the only human beings on the island, and the enchanting effect of the wild scenery, the vast expanse of sea, the distant moaning of the waters, the great rocks worn by the wind and the waves into all kinds of fantastic shapes and caverns, the blue sky above with the glorious sun shining upon us, all proclaimed to our minds the omnipotence of the great Creator of the Universe, the Almighty Maker and Giver of all.

We lingered as long as we could in these lonely and romantic solitudes, and, as we sped down the hill towards the boat, we suddenly became conscious that we had not thought either of what we should eat or what we should drink since we had breakfasted early in the morning, and we were very hungry. Walter was waiting for us on our side of the water, as he had been watching for our return, and had seen us coming when we were nearly a mile away. There was no vegetation to obstruct the view, for, as he said, we might walk fifty miles in Shetland without meeting with a bush or tree. We had an agreeable surprise when we reached the other side of the water in finding some light refreshments awaiting our arrival which he had thoughtfully provided in the event of their being required, and for which we were profoundly thankful. The cradle of Noss had disappeared some time before our visit, but, if it had been there, we should have been too terrified to make use of it. It had become dangerous, and as the pasturage of sheep on the Holm had proved a failure, the birds had again become masters of the situation, while the cradle had fallen to decay. Walter gave us an awful description of the danger of the fowler’s occupation, especially in the Foula Island, where the rocks rose towering a thousand feet above the sea. The top of the cliffs there often projected over their base, so that the fowler had to be suspended on a rope fastened to the top of the cliff, swinging himself backwards and forwards like a pendulum until he could reach the ledge of rock where the birds laid their eggs. Immediately he landed on it, he had to secure his rope, and then gather the eggs in a hoop net, and put them in his wallet, and then swing off again, perhaps hundreds of feet above the sea, to find another similar ledge, so that his business was practically carried on in the air. On one of these occasions a fowler had just reached a landing-place on the precipice, when his rope slipped out of his hand, and swung away from the cliff into the empty air. If he had hesitated one moment, he would have been lost for ever, as in all probability he would either have been starved to death on the ledge of rock on which he was or fallen exhausted into the sea below. The first returning swing of the rope might bring him a chance of grasping it, but the second would be too far away. The rope came back, the desperate man measured the distance with his eye, sprang forward in the air, grasped the rope, and was saved.

Sometimes the rope became frayed or cut by fouling some sharp edge of rock above, and, if it broke, the fowler was landed in eternity. Occasionally two or three men were suspended on the same rope at the same time. Walter told us of a father and two sons who were on the rope in this way, the father being the lowest and his two sons being above him, when the son who was uppermost saw that the rope was being frayed above him, and was about to break. He called to his brother who was just below that the rope would no longer hold them all, and asked him to cut it off below him and let their father go. This he indignantly refused to do, whereupon his brother, without a moment’s hesitation, cut the rope below himself, and both his father and brother perished.

It was terrible to hear such awful stories, as our nerves were unstrung already, so we asked our friend Walter not to pile on the agony further, and, after rewarding him for his services, we hurried over the remaining space of land and sea that separated us from our comfortable quarters at Lerwick, where a substantial tea was awaiting our arrival.

We were often asked what we thought of Shetland and its inhabitants.

Shetland was fine in its mountain and coast scenery, but it was wanting in good roads and forests, and it seemed strange that no effort had been made to plant some trees, as forests had formerly existed there, and, as a gentleman told us, there seemed no peculiarity in either the soil or climate to warrant an opinion unfavourable to the country’s arboricultural capacity. Indeed, such was the dearth of trees and bushes, that a lady, who had explored the country thoroughly, declared that the tallest and grandest tree she saw during her visit to the Islands was a stalk of rhubarb which had run to seed and was waving its head majestically in a garden below the old fort of Lerwick!

Agriculture seemed also to be much neglected, but possibly the fishing industry was more profitable. The cottages also were very small and of primitive construction, many of them would have been condemned as being unfit for human habitation if they had existed elsewhere, and yet, in spite of this apparent drawback, these hardy islanders enjoyed the best of health and brought up large families of very healthy-looking children. Shetland will always have a pleasant place in our memories, and, as regards the people who live there, to speak the truth we scarcely ever met with folks we liked better. We received the greatest kindness and hospitality, and met with far greater courtesy and civility than in the more outwardly polished and professedly cultivated parts of the countries further south, especially when making inquiries from people to whom we had not been “introduced”! The Shetlanders spoke good English, and seemed a highly intelligent race of people. Many of the men went to the whale and other fisheries in the northern seas, and “Greenland’s icy mountains” were well known to them.

On the island there were many wives and mothers who mourned the loss of husbands and sons who had perished in that dangerous occupation, and these remarks also applied to the Orkney Islands, to which we were returning, and might also account for so many of these women being dressed in black. Every one told us we were visiting the islands too late in the year, and that we ought to have made our appearance at an earlier period, when the sun never sets, and when we should have been able to read at midnight without the aid of an artificial light. Shetland was evidently in the range of the “Land of the Midnight Sun,” but whether we should have been able to keep awake in order to read at midnight was rather doubtful, as we were usually very sleepy. At one time of the year, however, the sun did not shine at all, and the Islanders had to rely upon the Aurora Borealis, or the Northern Lights, which then made their appearance and shone out brilliantly, spreading a beautifully soft light over the islands. We wondered if it were this or the light of the midnight sun that inspired the poet to write:

Night walked in beauty o’er the peaceful sea.

Whose gentle waters spoke tranquillity,

or if it had been borrowed from some more peaceful clime, as we had not yet seen the “peaceful sea” amongst these northern islands. We had now once more to venture on its troubled waters, and we made our appearance at the harbour at the appointed time for the departure of the St. Magnus. We were, however, informed that the weather was too misty for our boat to leave, so we returned to our lodgings, ordered a fire, and were just making ourselves comfortable and secretly hoping our departure might be delayed until morning, when Mrs. Sinclair, our landlady, came to tell us that the bell, which was the signal for the St. Magnus to leave, had just rung. We hurried to the quay, only to find that the boat which conveyed passengers and mails to our ship had disappeared. We were in a state of consternation, but a group of sailors, who were standing by, advised us to hire a special boat, and one was brought up immediately, by which, after a lot of shouting and whistling—for we could scarcely see anything in the fog—we were safely landed on the steamboat. We had only just got beyond the harbour, however, when the fog became so dense that we suddenly came to a standstill, and had to remain in the bay for a considerable time. When at last we moved slowly outwards, the hoarse whistle of the St. Magnus was sounded at short intervals, to avoid collision with any other craft. It had a strangely mournful sound, suggestive of a funeral or some great calamity, and we should almost have preferred being in a storm, when we could have seen the danger, rather than creeping along in the fog and darkness, with a constant dread of colliding with some other boat or with one of the dangerous rocks which we knew were in the vicinity. Sleep was out of the question until later, when the fog began to clear a little, and, in the meantime, we found ourselves in the company of a group of young men who told us they were going to Aberdeen.

One of them related a rather sorrowful story. He and his mates had come from one of the Shetland Islands from which the inhabitants were being expelled by the factor, so that he could convert the whole of the island into a sheep farm for his own personal advantage. Their ancestors had lived there from time immemorial, but their parents had all received notice to leave, and other islands were being depopulated in the same way. The young men were going to Aberdeen to try to find ships on which they could work their passage to some distant part of the world; they did not know or care where, but he said the time would come when this country would want soldiers and sailors, and would not be able to find them after the men had been driven abroad. He also told us about what he called the “Truck System,” which was a great curse in their islands, as “merchants” encouraged young people to get deeply in their debt, so that when they grew up they could keep them in their clutches and subject them to a state of semi-slavery, as with increasing families and low wages it was then impossible to get out of debt. We were very sorry to see these fine young men leaving the country, and when we thought of the wild and almost deserted islands we had just visited, it seemed a pity they could not have been employed there. We had a longer and much smoother passage than on our outward voyage, and the fog had given place to a fine, clear atmosphere as we once more entered the fine harbour of Kirkwall, and we had a good view of the town, which some enthusiastic passenger described as the “Metropolis of the Orcadean Archipelago.”

Tuesday, September 12th.

We narrowly escaped a bad accident as we were leaving the St. Magnus. She carried a large number of sheep and Shetland ponies on deck, and our way off the ship was along a rather narrow passage formed by the cattle on one side and a pile of merchandise on the other. The passengers were walking in single file, my brother immediately in front of myself, when one of the ponies suddenly struck out viciously with its hind legs just as we were passing. If we had received the full force of the kick, we should have been incapacitated from walking; but fortunately its strength was exhausted when it reached us, and it only just grazed our legs. The passengers behind thought at first we were seriously injured, and one of them rushed forward and held the animal’s head to prevent further mischief; but the only damage done was to our overalls, on which the marks of the pony’s hoofs remained as a record of the event. On reaching the landing-place the passengers all came forward to congratulate us on our lucky escape, and until they separated we were the heroes of the hour, and rather enjoyed the brief notoriety.

ST. MAGNUS CATHEDRAL KIRKWALL

There was an old-world appearance about Kirkwall reminiscent of the time

When Norse and Danish galleys plied

Their oars within the Firth of Clyde,

When floated Haco’s banner trim

Above Norwegian warriors grim,

Savage of heart and huge of limb.

for it was at the palace there that Haco, King of Norway, died in 1263. There was only one considerable street in the town, and this was winding and narrow and paved with flags in the centre, something like that in Lerwick, but the houses were much more foreign in appearance, and many of them had dates on their gables, some of them as far back as the beginning of the fifteenth century. We went to the same hotel as on our outward journey, and ordered a regular good “set out” to be ready by the time we had explored the ancient cathedral, which, like our ship, was dedicated to St. Magnus. We were directed to call at a cottage for the key, which was handed to us by the solitary occupant, and we had to find our way as best we could. After entering the ancient building, we took the precaution of locking the door behind us. The interior looked dark and dismal after the glorious sunshine we had left outside, and was suggestive more of a dungeon than a place of worship, and of the dark deeds done in the days of the past. The historian relates that St. Magnus met his death at the hands of his cousin Haco while in the church of Eigleshay. He had retired there with a presentiment of some evil about to happen him, and “while engaged in devotional exercises, prepared and resigned for whatever might occur, he was slain by one stroke of a hatchet. Being considered eminently pious, he was looked upon as a saint, and his nephew Ronald built the cathedral in accordance with a vow made before leaving Norway to lay claim to the Earldom of Orkney.” The cathedral was considered to be the best-preserved relic of antiquity in Scotland, and we were much impressed by the dim religious light which pervaded the interior, and quite bewildered amongst the dark passages inside the walls. We had been recommended to ascend the cathedral tower for the sake of the fine view which was to be obtained from the top, but had some difficulty in finding the way to the steps. Once we landed at the top of the tower we considered ourselves well repaid for our exertions, as the view over land and sea was very beautiful. Immediately below were the remains of the bishop’s and earl’s palaces, relics of bygone ages, now gradually crumbling to decay, while in the distance we could see the greater portion of the sixty-seven islands which formed the Orkney Group. Only about one-half of these were inhabited, the remaining and smaller islands being known as holms, or pasturages for sheep, which, seen in the distance, resembled green specks in the great blue sea, which everywhere surrounded them.

I should have liked to stay a little longer surveying this fairy-like scene, but my brother declared he could smell our breakfast, which by this time must have been waiting for us below. Our exit was a little delayed, as we took a wrong turn in the rather bewildering labyrinth of arches and passages in the cathedral walls, and it was not without a feeling of relief that we reached the door we had so carefully locked behind us. We returned the key to the caretaker, and then went to our hotel, where we loaded ourselves with a prodigious breakfast, and afterwards proceeded to walk across the Mainland of the Orkneys, an estimated distance of fifteen miles.

On our rather lonely way to Stromness we noticed that agriculture was more advanced than in the Shetland Islands, and that the cattle were somewhat larger, but we must say that we had been charmed with the appearance of the little Shetland ponies, excepting perhaps the one that had done its best to give us a farewell kick when we were leaving the St. Magnus. Oats and barley were the crops chiefly grown, for we did not see any wheat, and the farmers, with their wives and children, were all busy harvesting their crops of oats, but there was still room for extension and improvement, as we passed over miles of uncultivated moorland later. On our inquiring what objects of interest were to be seen on our way, our curiosity was raised to its highest pitch when we were told we should come to an underground house and to a large number of standing stones a few miles farther on. We fully expected to descend under the surface of the ground, and to find some cave or cavern below; but when we got to the place, we found the house practically above ground, with a small mountain raised above it. It was covered with grass, and had only been discovered in 1861, about ten years before our visit. Some boys were playing on the mountain, when one of them found a small hole which he thought was a rabbit hole, but, pushing his arm down it, he could feel no bottom. He tried again with a small stick, but with the same result. The boys then went to a farm and brought a longer stick, but again failed to reach the bottom of the hole, so they resumed their play, and when they reached home they told their parents of their adventure, and the result was that this ancient house was discovered and an entrance to it found from the level of the land below.

We went in search of the caretaker, and found him busy with the harvest in a field some distance away, but he returned with us to the mound. He opened a small door, and we crept behind him along a low, narrow, and dark passage for a distance of about seventeen yards, when we entered a chamber about the size of an ordinary cottage dwelling, but of a vault-like appearance. It was quite dark, but our guide proceeded to light a number of small candles, placed in rustic candlesticks, at intervals, round this strange apartment. We could then see some small cells in the wall, which might once have been used as burial places for the dead, and on the walls themselves were hundreds of figures or letters cut in the rock, in very thin lines, as if engraved with a needle. We could not decipher any of them, as they appeared more like Egyptian hieroglyphics than letters of our alphabet, and the only figure we could distinguish was one which had the appearance of a winged dragon.

The history of the place was unknown, but we were afterwards told that it was looked upon as one of the most important antiquarian discoveries ever made in Britain. The name of the place was Maeshowe. The mound was about one hundred yards in circumference, and it was supposed that the house, or tumulus, was first cut out of the rock and the earth thrown over it afterwards from the large trench by which it was surrounded.

Our guide then directed us to the “Standing Stones of Stenness,” which were some distance away; but he could not spare time to go with us, so we had to travel alone to one of the wildest and most desolate places imaginable, strongly suggestive of ghosts and the spirits of the departed. We crossed the Bridge of Brogar, or Bruargardr, and then walked along a narrow strip of land dividing two lochs, both of which at this point presented a very lonely and dismal appearance. Although they were so near together, Loch Harry contained fresh water only and Loch Stenness salt water, as it had a small tidal inlet from the sea passing under Waith Bridge, which we crossed later. There were two groups of the standing stones, one to the north and the other to the south, and each consisted of a double circle of considerable extent. The stones presented a strange appearance, as while many stood upright, some were leaning; others had fallen, and some had disappeared altogether. The storms of many centuries had swept over them, and “they stood like relics of the past, with lichens waving from their worn surfaces like grizzly beards, or when in flower mantling them with brilliant orange hues,” while the areas enclosed by them were covered with mosses, the beautiful stag-head variety being the most prominent. One of the poets has described them:

The heavy rocks of giant size

That o’er the land in circles rise.

Of which tradition may not tell,

Fit circles for the Wizard spell;

Seen far amidst the scowling storm

Seem each a tall and phantom form,

As hurrying vapours o’er them flee

Frowning in grim security,

While like a dread voice from the past

Around them moans the autumnal blast!

These lichened “Standing Stones of Stenness,” with the famous Stone of Odin about 150 yards to the north, are second only to Stonehenge, one measuring 18 feet in length, 5 feet 4 inches in breadth, and 18 inches in thickness. The Stone of Odin had a hole in it to which it was supposed that sacrificial victims were fastened in ancient times, but in later times lovers met and joined hands through the hole in the stone, and the pledge of love then given was almost as sacred as a marriage vow. An antiquarian description of this reads as follows: “When the parties agreed to marry, they repaired to the Temple of the Moon, where the woman in the presence of the man fell down on her knees and prayed to the God Wodin that he would enable her to perform, all the promises and obligations she had made, and was to make, to the young man present, after which they both went to the Temple of the Sun, where the man prayed in like manner before the woman. They then went to the Stone of Odin, and the man being on one side and the woman on the other, they took hold of each other’s right hand through the hole and there swore to be constant and faithful to each other.” The hole in the stone was about five feet from the ground, but some ignorant farmer had destroyed the stone, with others, some years before our visit.

There were many other stones in addition to the circles, probably the remains of Cromlechs, and there were numerous grass mounds, or barrows, both conoid and bowl-shaped, but these were of a later date than the circles. It was hard to realise that this deserted and boggarty-looking place was once the Holy Ground of the ancient Orcadeans, and we were glad to get away from it. We recrossed the Bridge of Brogar and proceeded rapidly towards Stromness, obtaining a fine prospective view of that town, with the huge mountain masses of the Island of Hoy as a background, on our way. These rise to a great height, and terminate abruptly near where that strange isolated rock called the “Old Man of Hoy” rises straight from the sea as if to guard the islands in the rear. The shades of evening were falling fast as we entered Stromness, but what a strange-looking town it seemed to us! It was built at the foot of the hill in the usual irregular manner and in one continuous crooked street, with many of the houses with their crow-stepped gables built as it were over the sea itself, and here in one of these, owing to a high recommendation received inland, we stayed the night. It was perched above the water’s edge, and, had we been so minded, we might have caught the fish named sillocks for our own breakfast without leaving the house: many of the houses, indeed, had small piers or landing-stages attached to them, projecting towards the bay.

We found Mrs. Spence an ideal hostess and were very comfortable, the only drawback to our happiness being the information that the small steamboat that carried mails and passengers across to Thurso had gone round for repairs “and would not be back for a week, but a sloop would take her place” the day after to-morrow. But just fancy crossing the stormy waters of the Pentland Firth in a sloop! We didn’t quite know what a sloop was, except that it was a sailing-boat with only one mast; but the very idea gave us the nightmare, and we looked upon ourselves as lost already. The mail boat, we had already been told, had been made enormously strong to enable her to withstand the strain of the stormy seas, besides having the additional advantage of being propelled by steam, and it was rather unfortunate that we should have arrived just at the time she was away. We asked the reason why, and were informed that during the summer months seaweeds had grown on the bottom of her hull four or five feet long, which with the barnacles so impeded her progress that it was necessary to have them scraped off, and that even the great warships had to undergo the same process.

Seaweeds of the largest size and most beautiful colours flourish, in the Orcadean seas, and out of 610 species of the flora in the islands we learned that 133 were seaweeds. Stevenson the great engineer wrote that the large Algæ, and especially that one he named the “Fucus esculentus,” grew on the rocks from self-grown seed, six feet in six months, so we could quite understand how the speed of a ship would be affected when carrying this enormous growth on the lower parts of her hull.

Wednesday, September 13th.

We had the whole of the day at our disposal to explore Stromness and the neighbourhood, and we made the most of it by rambling about the town and then along the coast to the north, but we were seldom out of sight of the great mountains of Hoy.

Sir Walter Scott often visited this part of the Orkneys, and some of the characters he introduced in his novels were found here. In 1814 he made the acquaintance of a very old woman near Stromness, named Bessie Miller, whom he described as being nearly one hundred years old, withered and dried up like a mummy, with light blue eyes that gleamed with a lustre like that of insanity. She eked out her existence by selling favourable winds to mariners, for which her fee was sixpence, and hardly a mariner sailed out to sea from Stromness without visiting and paying his offering to Old Bessie Miller. Sir Walter drew the strange, weird character of “Norna of the Fitful Head” in his novel The Pirate from her.

The prototype of “Captain Cleveland” in the same novel was John Gow, the son of a Stromness merchant. This man went to sea, and by some means or other became possessed of a ship named the Revenge, which carried twenty-four guns. He had all the appearance of a brave young officer, and on the occasions when he came home to see his father he gave dancing-parties to his friends. Before his true character was known—for he was afterwards proved to be a pirate—he engaged the affections of a young lady of fortune, and when he was captured and convicted she hastened to London to see him before he was executed; but, arriving there too late, she begged for permission to see his corpse, and, taking hold of one hand, she vowed to remain true to him, for fear, it was said, of being haunted by his ghost if she bestowed her hand upon another.

It is impossible to visit Stromness without hearing something of that famous geologist Hugh Miller, who was born at Cromarty in the north of Scotland in the year 1802, and began life as a quarry worker, and wrote several learned books on geology. In one of these, entitled Footprints of the Creator in the Asterolepis of Stromness, he demolished the Darwinian theory that would make a man out to be only a highly developed monkey, and the monkey a highly developed mollusc. My brother had a very poor opinion of geologists, but his only reason for this seemed to have been formed from the opinion of some workmen in one of our brickfields. A gentleman who took an interest in geology used to visit them at intervals for about half a year, and persuaded the men when excavating the clay to put the stones they found on one side so that he could inspect them, and after paying many visits he left without either thanking them or giving them the price of a drink! But my brother was pleased with Hugh Miller’s book, for he had always contended that Darwin was mistaken, and that instead of man having descended from the monkey, it was the monkey that had descended from the man. I persuaded him to visit the museum, where we saw quite a number of petrified fossils. As there was no one about to give us any information, we failed to find Hugh Miller’s famous asterolepis, which we heard afterwards had the appearance of a petrified nail, and had formed part of a huge fish whose species were known to have measured from eight to twenty-three feet in length. It was only about six inches long, and was described as one of the oldest, if not the oldest, vertebrate fossils hitherto discovered. Stromness ought to be the Mecca, the happy hunting-ground, or the Paradise to geologists, for Hugh Miller has said it could furnish more fossil fish than any other geological system in England, Scotland, and Wales, and could supply ichthyolites by the ton, or a ship load of fossilised fish sufficient to supply the museums of the world. How came this vast number of fish to be congregated here? and what was the force that overwhelmed them? It was quite evident from the distorted portions of their skeletons, as seen in the quarried flags, that they had suffered a violent death. But as we were unable to study geology, and could neither pronounce nor understand the names applied to the fossils, we gave it up in despair, as a deep where all our thoughts were drowned.

We then walked along the coast, until we came to the highest point of the cliffs opposite some dangerous rocks called the Black Craigs, about which a sorrowful story was told. It happened on Wednesday, March 5th, 1834, during a terrific storm, when the Star of Dundee, a schooner of about eighty tons, was seen to be drifting helplessly towards these rocks. The natives knew there was no chance of escape for the boat, and ran with ropes to the top of the precipice near the rocks in the hope of being of some assistance; but such was the fury of the waves that the boat was broken into pieces before their eyes, and they were utterly helpless to save even one of their shipwrecked fellow-creatures. The storm continued for some time, and during the remainder of the week nothing of any consequence was found, nor was any of the crew heard of again, either dead or alive, till on the Sunday morning a man was suddenly observed on the top of the precipice waving his hands, and the people who saw him first were so astonished that they thought it was a spectre. It was afterwards discovered that it was one of the crew of the ill-fated ship who had been miraculously saved. He had been washed into a cave from a large piece of the wreck, which had partially blocked its entrance and so checked the violence of the waves inside, and there were also washed in from the ship some red herrings, a tin can which had been used for oil, and two pillows. The herrings served him for food and the tin can to collect drops of fresh water as they trickled down the rocks from above, while one of the pillows served for his bed and he used the other for warmth by pulling out the feathers and placing them into his boots. Occasionally when the waves filled the mouth of the cave he was afraid of being suffocated. Luckily for him at last the storm subsided sufficiently to admit of his swimming out of the cave; how he managed to scale the cliffs seemed little short of a miracle. He was kindly treated by the Islanders, and when he recovered they fitted him out with clothing so that he could join another ship. By what we may call the irony of fate he was again shipwrecked some years afterwards. This time the fates were less kind, for he was drowned!

We had a splendid view of the mountains and sea, and stayed as usual on the cliffs until the pangs of hunger compelled us to return to Stromness, where we knew that a good tea was waiting for us. At one point on our way back the Heads of Hoy strangely resembled the profile of the great Sir Walter Scott, and this he would no doubt have seen when collecting materials for The Pirate.

We had heard both in Shetland and Orkney that when we reached John o’ Groat’s we should find an enormous number of shells on the beach, and as we had some extensive rockeries at home already adorned with thousands of oyster shells, in fact so many as to cause our home to be nicknamed “Oyster Shell Hall,” we decided to gather some of the shells when we got to John o’Groat’s and send them home to our friends. The question of packages, however, seemed to be rather a serious one, as we were assured over and over again we should find no packages when we reached that out-of-the-way corner of Scotland, and that in the whole of the Orkney Islands there were not sufficient willows grown to make a single basket, skip, or hamper. So after tea we decided to explore the town in search of a suitable hamper, and we had some amusing experiences, as the people did not know what a hamper was. At length we succeeded in finding one rather ancient and capacious basket, but without a cover, whose appearance suggested that it had been washed ashore from some ship that had been wrecked many years ago, and, having purchased it at about three times its value, we carried it in triumph to our lodgings, to the intense amusement of our landlady and the excited curiosity of the Stromnessians.

We spent the remainder of the evening in looking through Mrs. Spence’s small library of books, but failed to find anything very consoling to us, as they related chiefly to storms and shipwrecks, and the dangerous nature of the Pentland Firth, whose turbulent waters we had to cross on the morrow.

The Pentland Firth lies between the north of Scotland and the Orkney Islands, varies from five and a half to eight miles in breadth, and is by repute the most dangerous passage in the British Isles. We were told in one of the books that if we wanted to witness a regular “passage of arms” between two mighty seas, the Atlantic at Dunnet Head on the west, and the North Sea at Duncansbay Head on the east, we must cross Pentland Firth and be tossed upon its tides before we should be able to imagine what might be termed their ferocity. “The rush of two mighty oceans, struggling to sweep this world of waters through a narrow sound, and dashing their waves in bootless fury against the rocky barriers which headland and islet present; the endless contest of conflicting tides hurried forward and repelled, meeting, and mingling—their troubled surface boiling and spouting—and, even in a summer calm, in an eternal state of agitation”; and then fancy the calm changing to a storm: “the wind at west; the whole volume of the Atlantic rolling its wild mass of waters on, in one sweeping flood, to dash and burst upon the black and riven promontory of the Dunnet Head, until the mountain wave, shattered into spray, flies over the summit of a precipice, 400 feet above the base it broke upon.” But this was precisely what we did not want to see, so we turned to the famous Statistical Account, which also described the difficulty of navigating the Firth for sailing vessels. This informed us that “the current in the Pentland Firth is exceedingly strong during the spring tides, so that no vessel can stem it. The flood-tide runs from west to east at the rate of ten miles an hour, with new and full moon. It is then high water at Scarfskerry (about three miles away from Dunnet Head) at nine o’clock. Immediately, as the water begins to fall on the shore, the current turns to the west; but the strength of the flood is so great in the middle of the Firth that it continues to run east till about twelve. With a gentle breeze of westerly wind, about eight o’clock in the morning the whole Firth, from Dunnet Head to Hoy Head in Orkney, seems as smooth as a sheet of glass. About nine the sea begins to rage for about one hundred yards off the Head, while all without continues smooth as before. This appearance gradually advances towards the Firth, and along the shore to the east, though the effects are not much felt along the shore till it reaches Scarfskerry Head, as the land between these points forms a considerable bay. By two o’clock the whole of the Firth seems to rage. About three in the afternoon it is low water on the shore, when all the former phenomena are reversed, the smooth water beginning to appear next the land and advancing gradually till it reaches the middle of the Firth. To strangers the navigation is very dangerous, especially if they approach near to land. But the natives along the coast are so well acquainted with the direction of the tides, that they can take advantage of every one of these currents to carry them safe from one harbour to another. Hence very few accidents happen, except from want of skill or knowledge of the tides.”

There were some rather amusing stories about the detention of ships in the Firth. A Newcastle shipowner had despatched two ships from that port by the same tide, one to Bombay by the open sea, and the other, via the Pentland Firth, to Liverpool, and the Bombay vessel arrived at her destination first. Many vessels trying to force a passage through the Firth have been known to drift idly about hither and thither for months before they could get out again, and some ships that once entered Stromness Bay on New Year’s Day were found there, resting from their labours on the fifteenth day of April following, “after wandering about like the Flying Dutchman.” Sir Walter Scott said this was formerly a ship laden with precious metals, but a horrible murder was committed on board. A plague broke out amongst the crew, and no port would allow the vessel to enter for fear of contagion, and so she still wanders about the sea with her phantom crew, never to rest, but doomed to be tossed about for ever. She is now a spectral ship, and hovers about the Cape of Good Hope as an omen of bad luck to mariners who are so unfortunate as to see her.

The dangerous places at each end of the Firth were likened to the Scylla and Charybdis between Italy and Sicily, where, in avoiding one mariners were often wrecked by the other; but the dangers in the Firth were from the “Merry Men of Mey,” a dangerous expanse of sea, where the water was always boiling like a witch’s cauldron at one end, and the dreaded “Swalchie Whirlpool” at the other. This was very dangerous for small boats, as they could sail over it safely in one state of the tide, but when it began to move it carried the boat round so slowly that the occupants did not realise their danger until too late, when they found themselves going round quicker and quicker as they descended into the awful vortex below, where the ancient Vikings firmly believed the submarine mill existed which ground the salt that supplied the ocean.

We ought not to have read these dismal stories just before retiring to rest, as the consequence was that we were dreaming of dangerous rocks, storms, and shipwrecks all through the night, and my brother had toiled up the hill at the back of the town and found Bessie Miller there, just as Sir Walter Scott described her, with “a clay-coloured kerchief folded round her head to match the colour of her corpse-like complexion.” He was just handing her a sixpence to pay for a favourable wind, when everything was suddenly scattered by a loud knock at the door, followed by the voice of our hostess informing us that it was five o’clock and that the boat was “awa’ oot” at six.

We were delighted to find that in place of the great storm pictured in our excited imagination there was every prospect of a fine day, and that a good “fish breakfast” served in Mrs. Spence’s best style was waiting for us below stairs.

Thursday, September 14th.

After bidding Mrs. Spence farewell, and thanking her for her kind attention to us during our visit to Stromness, we made our way to the sloop, which seemed a frail-looking craft to cross the stormy waters of the Pentland Firth. We did not, of course, forget our large basket which we had had so much difficulty in finding, and which excited so much attention and attracted so much curiosity towards ourselves all the way to John o’ Groat’s. It even caused the skipper to take a friendly interest in us, for after our explanation he stored that ancient basket amongst his more valuable cargo.

There was only a small number of passengers, but in spite of the early hour quite a little crowd of people had assembled to witness our departure, and a considerable amount of banter was going on between those on board the sloop and the company ashore, which continued as we moved away, each party trying to get the better of the other. As a finale, one of our passengers shouted to his friend who had come to see him off: “Do you want to buy a cow?” “Yes,” yelled his friend, “but I see nothing but a calf.” A general roar of laughter followed this repartee, as we all thought the Orkneyman on shore had scored. We should have liked to have fired another shot, but by the time the laughter had subsided we were out of range. We did not expect to be on the way more than three or four hours, as the distance was only about twenty-four miles; but we did not reach Thurso until late in the afternoon, and we should have been later if we had had a less skilful skipper. In the first place we had an unfavourable wind, which prevented our sailing by the Hoy Sound, the shortest and orthodox route, and this caused us to miss the proper sea view of the “Old Man of Hoy,” which the steamboat from Stromness to Thurso always passed in close proximity, but we could perceive it in the distance as an insular Pillar of Rock, standing 450 feet high with rocks in vicinity rising 1,000 feet, although we could not see the arch beneath, which gives it the appearance of standing on two legs, and hence the name given to the rock by the sailors. The Orcadean poet writes:

See Hoy’s Old Man whose summit bare

Pierces the dark blue fields of air;

Based in the sea, his fearful form

Glooms like the spirit of the storm.

When pointing out the Old Man to us, the captain said that he stood in the roughest bit of sea round the British coast, and the words “wind and weather permitting” were very applicable when stoppages wore contemplated at the Old Man or other places in these stormy seas.

We had therefore to sail by way of Lang Hope, which we supposed was a longer route, and we were astonished at the way our captain handled his boat; but when we reached what we thought was Lang Hope, he informed the passengers that he intended to anchor here for some time, and those who wished could be ferried ashore. We had decided to remain on the boat, but when the captain said there was an inn there where refreshments could be obtained, my brother declared that he felt quite hungry, and insisted upon our having a second breakfast. We were therefore rowed ashore, and were ushered into the parlour of the inn as if we were the lords of the manor and sole owners, and were very hospitably received and entertained. The inn was appropriately named the “Ship,” and the treatment we received was such as made us wish we were making a longer stay, but time and tide wait for no man.

For the next inn he spurs amain,

In haste alights, and scuds away—

But time and tide for no man stay.

Whether it was for time or tide or for one of those mysterious movements in the Pentland Firth that our one-masted boat was waiting we never knew. We had only just finished our breakfast when a messenger appeared to summon us to rejoin the sloop, which had to tack considerably before we reached what the skipper described as the Scrabster Roads. A stiff breeze had now sprung up, and there was a strong current in the sea; at each turn or tack our boat appeared to be sailing on her side, and we were apprehensive that she might be blown over into the sea. We watched the operations carefully and anxiously, and it soon became evident that what our skipper did not know about the navigation of these stormy seas was not worth knowing. We stood quite near him (and the mast) the whole of the time, and he pointed out every interesting landmark as it came in sight. He seemed to be taking advantage of the shelter afforded by the islands, as occasionally we came quite near their rocky shores, and at one point he showed us a small hole in the rock which was only a few feet above the sea; he told us it formed the entrance to a cave in which he had often played when, as a boy, he lived on that island.

The time had now arrived to cross the Pentland Firth and to sail round Dunnet Head to reach Thurso. Fortunately the day was fine, and the strong breeze was nothing in the shape of a storm; but in spite of these favourable conditions we got a tossing, and no mistake! Our little ship was knocked about like a cork on the waters, which were absolutely boiling and foaming and furiously raging without any perceptible cause, and as if a gale were blowing on them two ways at once. The appearance of the foaming mass of waters was terrible to behold; we could hear them roaring and see them struggling together just below us; the deck of the sloop was only a few feet above them, and it appeared as if we might be swallowed up at any moment. The captain told us that this turmoil was caused by the meeting of the waters of two seas, and that at times it was very dangerous to small boats.

Many years ago he was passing through the Firth with his boat on a rather stormy day, when he noticed he was being followed by another boat belonging to a neighbour of his. He could see it distinctly from time to time, and he was sure that it could not be more than 200 yards away, when he suddenly missed it. He watched anxiously for some time, but it failed to reappear, nor was the boat or its crew ever seen or heard of again, and it was supposed to have been carried down by a whirlpool!

We were never more thankful than when we got safely across those awful waters and the great waves we encountered off Dunnet Head, and when we were safely landed near Thurso we did not forget the skipper, but bade him a friendly and, to him, lucrative farewell.

We had some distance to walk before reaching the town where, loaded with our luggage and carrying the large basket between us, each taking hold of one of the well-worn handles, we attracted considerable attention, and almost every one we saw showed a disposition to see what we were carrying in our hamper; but when they discovered it was empty, their curiosity was turned into another channel, and they must see where we were taking it; so by the time we reached the house recommended by our skipper for good lodgings we had a considerable following of “lookers on.” Fortunately, however, no one attempted to add to our burden by placing anything in the empty basket or we should have been tempted to carry it bottom upwards like an inmate of one of the asylums in Lancashire. A new addition was being built in the grounds, and some of the lunatics were assisting in the building operations, when the foreman discovered one of them pushing his wheelbarrow with the bottom upwards and called out to him, “Why don’t you wheel it the right way up?”

“I did,” said the lunatic solemnly, “but they put bricks in it!”

We felt that some explanation was due to our landlady, who smiled when she saw the comical nature of that part of our luggage and the motley group who had followed us, and as we unfolded its history and described the dearth of willows in the Orkneys, the price we had paid, the difficulties in finding the hamper, and the care we had taken of it when crossing the stormy seas, we could see her smile gradually expanding into a laugh that she could retain no longer when she told us we could have got a better and a cheaper basket than that in the “toon,” meaning Thurso, of course. It was some time before we recovered ourselves, laughter being contagious, and we could hear roars of it at the rear of the house as our antiquated basket was being stored there.

After tea we crossed the river which, like the town, is named Thurso, the word, we were informed, meaning Thor’s House. Thor, the god of thunder, was the second greatest of the Scandinavian deities, while his father, Odin, the god of war, was the first. We had some difficulty in crossing the river, as we had to pass over it by no less than eighty-five stepping-stones, several of which were slightly submerged. Here we came in sight of Thurso Castle, the residence of the Sinclair family, one of whom, Sir John Sinclair, was the talented author of the famous Statistical Account of Scotland, and a little farther on stood Harold’s Tower. This tower was erected by John Sinclair over the tomb of Earl Harold, the possessor at one time of one half of Orkney, Shetland, and Caithness, who fell in battle against his own namesake, Earl Harold the Wicked, in 1190. In the opposite direction was Scrabster and its castle, the scene of the horrible murder of John, Earl of Caithness, in the twelfth century, “whose tongue was cut from his throat and whose eyes were put out.” We did not go there, but went into the town, and there witnessed the departure of the stage, or mail coach, which was just setting out on its journey of eighty miles, for railways had not yet made their appearance in Caithness, the most northerly county in Scotland. We then went to buy another hamper, and got a much better one for less money than we paid at Stromness, for we had agreed that we would send home two hampers filled with shells instead of one. We also inquired the best way of getting to John o’ Groat’s, and were informed that the Wick coach would take us the first six miles, and then we should have to walk the remaining fifteen. We were now only one day’s journey to the end and also from the beginning of our journey, and, as may easily be imagined, we were anxiously looking forward to the morrow.

Friday, September 15th.

At eight o’clock in the morning we were comfortably seated in the coach which was bound for Wick, with our luggage and the two hampers safely secured on the roof above, and after a ride of about six miles we were left, with our belongings, at the side of the highway where the by-road leading in the direction of John o’ Groat’s branched off to the left across the open country. The object of our walk had become known to our fellow-passengers, and they all wished us a pleasant journey as the coach moved slowly away. Two other men who had friends in the coach also alighted at the same place, and we joined them in waving adieux, which were acknowledged from the coach, as long as it remained in sight. They also very kindly assisted us to carry our luggage as far as they were going on our way, and then they helped us to scheme how best to carry it ourselves. We had brought some strong cord with us from Thurso, and with the aid of this they contrived to sling the hampers over our shoulders, leaving us free to carry the remainder of our luggage in the usual way, and then, bidding us a friendly farewell, left us to continue on our lonely way towards John o’ Groat’s. We must have presented an extraordinary appearance with these large baskets extending behind our backs, and we created great curiosity and some amusement amongst the men, women, and children who were hard at work harvesting in the country through which we passed.

My brother said it reminded him of Christian in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, who carried the burden on his back and wanted to get rid of it; while I thought of Sinbad the Sailor, who, when wrecked on a desert island, was compelled to carry the Old Man of the Sea on his shoulders, and he also wanted to get rid of his burden; but we agreed that, like both of these worthy characters, we should be obliged to carry our burdens to the end of the journey.

We had a fine view of Dunnet Head, which is said to be the Cape Orcas mentioned by Diodorus Siculus, the geographer who lived in the time of Julius Cæsar, and of the lighthouse which had been built on the top of it in 1832, standing quite near the edge of the cliff.

The light from the lantern, which was 346 feet above the highest spring tide, could be seen at a distance of 23 miles; but even this was sometimes obscured by the heavy storms from the west when the enormous billows from the Atlantic dashed against the rugged face of the cliff and threw up the spray as high as the lights of the building itself, so that the stones they contained have been known to break the glass in the building; such, indeed, was the prodigious combined force of the wind and sea upon the headland, that the very rock seemed to tremble as if it were affected by an earthquake.

While on the coach we had passed the hamlets of Murkle and Castlehill. Between these two places was a sandy pool on the seashore to which a curious legend was attached. The story goes that—

a young lad on one occasion discovered a mermaid bathing and by some means or other got into conversation with her and rendered himself so agreeable that a regular meeting at the same spot took place between them. This continued for some time. The young man grew exceedingly wealthy, and no one could tell how he became possessed of such riches. He began to cut a dash amongst the lasses, making them presents of strings of diamonds of vast value, the gifts of the fair sea nymph. By and by he began to forget the day of his appointment; and when he did come to see her, money and jewels were his constant request. The mermaid lectured him pretty sharply on his love of gold, and, exasperated at his perfidy in bestowing her presents on his earthly fair ones, enticed him one evening rather farther than usual, and at length showed him a beautiful boat, in which she said she would convey him to a cave in Darwick Head, where she had all the wealth of all the ships that ever were lost in the Pentland Firth and on the sands of Dunnet. He hesitated at first, but the love of gold prevailed, and off they set to the cave in question. And here, says the legend, he is confined with a chain of gold, sufficiently long to admit of his walking at times on a small piece of sand under the western side of the Head; and here, too, the fair siren laves herself in the tiny waves on fine summer evenings, but no consideration will induce her to loose his fetters of gold, or trust him one hour out of her sight.

We walked on at a good pace and in high spirits, but, after having knocked about for nine days and four nights and having travelled seven or eight hundred miles by land and sea, the weight of our extra burden began to tell upon us, and we felt rather tired and longed for a rest both for mind and body in some quiet spot over the week’s end, especially as we had decided to begin our long walk on the Monday morning.