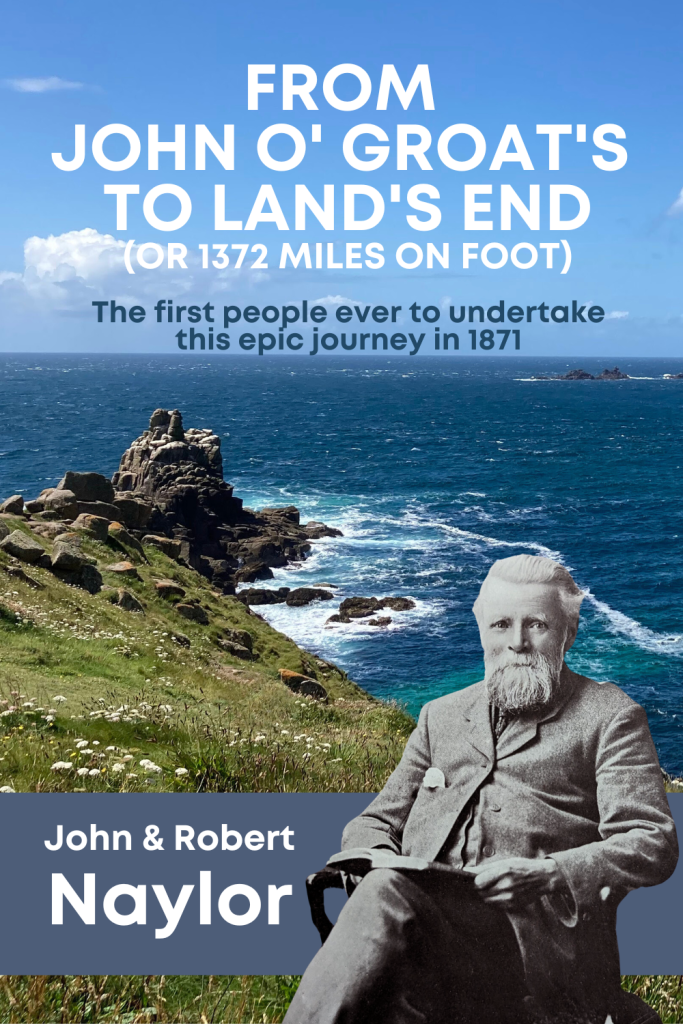

FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) My Great Great Grandfather, John Naylor and his brother Robert where the first people to walk from From John O Groat’s to Lands End in 1871. Read the book in full for free here on http://www.nearlyuphill.co.uk in chapters or download their 660 page book here – FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) All words are written by them and all pictures are taken from the original book which was written in 1916 by John Naylor.

NINTH WEEK’S JOURNEY — Nov. 13 to Nov. 18.

Torbay — Cockington — Compton Castle — Marldon — Berry Pomeroy — River Dart — Totnes — Sharpham — Dittisham — Dartmouth — Totnes ¶ Dartmoor — River Erme — Ivybridge — Plymouth ¶ Devonport — St. Budeaux — Tamerton Foliot — Buckland Abbey — Walkhampton — Merridale — River Tavy — Tavistock — Hingston Downs — Callington — St. Ive — Liskeard ¶ St. Neot — Restormel Castle — Lostwithiel — River Fowey — St. Blazey — St. Austell — Truro ¶ Perranarworthal — Penryn — Helston — The Lizard — St. Breage — Perran Downs — Marazion — St. Michael’s Mount — Penzance ¶ Newlyn — St. Paul — Mousehole — St. Buryan — Treryn — Logan Rock — St. Levan — Tol-Peden-Penwith — Sennen — Land’s End — Penzance ¶¶

NINTH WEEK’S JOURNEY

Monday, November 13th.

From time immemorial Torbay had been a favourite landing-place both for friends and foes, and it was supposed that the Roman Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Adrian, when on their way to the camp on Milber Downs, had each landed near the place where Brixham now stands. Brixham was the best landing-place in the Bay, and the nearest to the open sea. It was a fishing-place of some importance when Torquay, its neighbour, was little known, except perhaps as a rendezvous of smugglers and pirates. Leland, in his famous Itinerary written in the sixteenth century, after describing the Bay of Torre as being about four miles across the entrance and “ten miles or more in compace,” says: “The Fishermen hath divers tymes taken up with theyr nettes yn Torre-bay mussons of harts, whereby men judge that in tymes paste it hath been forest grounds.” Clearly much of England has been washed away or has sunk beneath the ocean. Is not this part of the “Lyonesse” of the poets—the country of romance—the land of the fairies?

In 1588, when the Spanish Armada appeared outside the Bay, there was great excitement in the neighbourhood of Torbay, which grew into frenzy when the first capture was towed in. The Rosario, or, to give her the full name, Nuestra Señora del Rosario, was a fine galleon manned by 450 men and many gallant officers. She was the capitana, or flagship, of the squadron commanded by Don Pedro de Valdez, who had seen much service in the West Indies and who, because of his special knowledge of the English Channel, was of great importance in the council of the Armada. He was a bold, skilful leader, very different from the Commander-in-Chief, and as his ship formed one of the rearguard he took an early part in the fight with the pursuing English. He was badly mauled, losing his foremast and suffering worse by fouling two ships, one of his own squadron, the other a Biscayan; all three were damaged. He demanded assistance of Medina Sidonia, but the weather was rough and the Duke refused. In the darkness the Rosario drove off one or two English attempts to cut her off, but Drake himself in the famous Revenge lay alongside and called upon Valdez to surrender. His reply was a demand for honourable terms, to which Drake answered that he had no time for parley—the Spanish commander must come aboard at once or he would rake her. The name of Drake (El Draque, the Dragon) was enough for the Spaniard, and Valdez, in handing over his sword, took credit to himself that he yielded to the most famous captain of his day. Drake in reply promised good treatment and all the lives of the crew, a thing by no means usual, as can be guessed by the remark of the disgusted Sheriff, when so many prisoners were handed over at Torbay; he wished “the Spaniards had been made into water-spaniels.” Drake sent the Roebuck to see the ship safely into Torbay, where she was left in charge of the Brixham fishermen, her powder being secured at once and sent by the quickest of the fishing-boats to our own ships, at that moment badly in need of it. The prisoners were taken round to Torbay, where they were lodged in a building ever afterwards known as the “Spanish barn.”

STATUE OF WILLIAM, PRINCE OF ORANGE, BRIXHAM, ERECTED ON THE SPOT WHERE HE LANDED.

In 1601 the first squadron organised by the East India Company sailed from Torbay, and in 1667 the Dutch fleet, commanded by De Ruyter, paid the Bay a brief but not a friendly visit, doing some damage. In 1688 another fleet appeared—this time a friendly one, for it brought William, Prince of Orange, who had been invited to occupy the English throne abdicated by James II. We were informed that when his ship approached the shore he spoke to the people assembled there in broken English—very broken—saying, “Mine goot people, mine goot people, I mean you goot; I am come here for your goot, for your goots,” and suggested that if they were willing to welcome him they should come and fetch him ashore; whereupon one Peter Varwell ran into the sea, and carried the new King to the shore, gaining much renown for doing so. This happened on November 5th, the date for landing doubtless having been arranged to coincide with the anniversary of the attempt of Guy Fawkes to blow up the Houses of Parliament with gunpowder eighty-three years before, so that bonfire day served afterwards to celebrate the two occasions. The house where William stayed that night was still pointed out in Brixham.

In 1690 James II, who had been dethroned and exiled to France, told Tourville, the French Admiral, that if he would take his fleet to the South of England he would find all the people there ready to receive him back again, so he brought his ships off Torbay. Instead of a friendly reception here, he found the people decidedly hostile to James’s cause, so he detached two or three of his galleys to Teignmouth, quite a defenceless place, where they committed great ravages and practically destroyed the town. These galleys were a class of boat common in the Mediterranean, where they had been employed ever since the warlike times of the Greeks and Romans. In addition to sails, they were propelled with oars manned by slaves; and a similar class of ship worked by convicts was used by the French down to the middle of the eighteenth century. The men of Teignmouth, who had no wish to be captured and employed as galley slaves, seeing that they were in a hopeless position, retreated inland. Lord Macaulay thus describes the position in his History:

The Beacon on the ridge above Teignmouth was kindled, Hey-Tor and Cawsand made answer, and soon all the hill tops of the West were on fire. Messengers were riding all night from deputy lieutenant to deputy lieutenant; and early the next morning, without chief, without summons, five hundred gentlemen and yeomen, armed and mounted, had assembled on the summit of Haldon Hill, and in twenty-four hours all Devonshire was up.

It was therefore no wonder that Trouville found his landing opposed by thousands of fierce Devonshire men, who lined the shores and prevented him from landing his troops; the expedition was a complete failure, and he returned to France.

In those days, when railways and telegraphy were unknown, the whole country could be aroused very quickly and effectively by those beacon fires. The fuel was always kept ready for lighting on the Beacon hills, which were chosen so that the fire on one hill could be seen from the other. On our journey through England we passed many of these beacons, then used for more peaceful purposes.

In 1815 another ship appeared in Torbay, with only one prisoner on board, but a very important one. The ship was the British man-of-war the Bellerophon, and the prisoner the great Napoleon Bonaparte. We had already come to the conclusion that Torquay, with its pretty bay, was the most delightful place we had visited; and even Napoleon, who must have been acquainted with the whole of Europe, and who appeared in Torbay under what must have been to him depressing circumstances, exclaimed when he saw it, “Enfin, voilà un beau pays!” (What a beautiful country this is!) He arrived on July 24th, five weeks after the Battle of Waterloo, and departed on August 8th from Plymouth, having been transferred to the Northumberland for the voyage to his prison home in St. Helena, a South Atlantic island 760 miles from any other land, and where he died in 1821. During the few days’ visit of the Bellerophon at Torbay, thousands upon thousands of people came by land and water in the hope of seeing the great general who had so nearly made himself master of the whole of Europe, and although very few of them saw Napoleon, they all saw the lovely scenery there, and this, it was said, laid the foundation of the fortunes of the future Torquay.

NAPOLEON ON THE BELLEROPHON.

From the Painting by Orchardson.

We had intended leaving Torquay for Totnes by the main road, which passed through Paignton, but our host informed us that even if we passed through it, we should not see Paignton in all its glory, as we were twelve years too early for one pudding and thirty-nine years too late for the next. We had never heard of Paignton puddings before, but it appeared that as far back as 1294 Paignton had been created a borough or market town, and held its charter by a White-Pot Pudding, which was to take seven years to make, seven years to bake, and seven years to eat, and was to be produced once every fifty years. In 1809 the pudding was made of 400 lbs. of flour, 170 lbs. of suet, 140 lbs. of raisins, and 240 eggs. It was boiled in a brewer’s copper, and was kept constantly boiling from the Saturday morning until the Tuesday following, when it was placed on a gaily decorated trolley and drawn through the town by eight oxen, followed by a large and expectant crowd of people. But the pudding did not come up to expectations, turning out rather stodgy: so in 1859 a much larger pudding was made, but this time it was baked instead of boiled, and was drawn by twenty-five horses through the streets of the town. One feature of the procession on that occasion was a number of navvies who happened to be working near the town and who walked in their clean white slops, or jackets, and of course came in for a goodly share of the pudding.

One of the notables of Paignton was William Adams, one of the many prisoners in the hands of the Turks or Saracens in the time when the English Liturgy was compiled. It was said that the intercession “for all prisoners and captives” applied especially to them, and every Sunday during the five years he was a prisoner at Algiers, William Adams’ name was specially mentioned after that petition. The story of his escape was one of the most sensational of its time. Adams and six companions made a boat in sections, and fastened it together in a secluded cove on the seacoast; but after it was made they found it would only carry five of them, of whom Adams was of course one. After the most terrible sufferings they at length reached “Majork,” or Majorca Island, the Spaniards being very kind to them, assisting them to reach home, where they arrived emaciated and worn out. The two men left behind were never heard of again. We had often heard the name “Bill Adams,” and wondered whether this man could have been the original. The county historian of those days had described him as “a very honest sensible man, who died in the year of our Lord 1687, and his body, so like to be buried in the sea and to feed fishes, lies buried in Paignton churchyard, where it feasteth worms.”

We could see Paignton, with its ivy-covered Tower, all that was left of the old Palace of the Bishops of Exeter, but we did not visit it, as we preferred to cross the hills and see some other places of which we had heard, and also to visit Berry Pomeroy Castle on our way to Totnes.

Behind Torquay we passed along some of the loveliest little lanes we had ever seen. They must have presented a glorious picture in spring and summer, when the high hedges were “hung with ferns and banked up with flowers,” for even in November they were very beautiful. These by-lanes had evidently been originally constructed for pedestrian and horse traffic, but they had not been made on the surface of the land, like those in Dorset and Wilts, and were more like ditches than roads. We conjectured that they had been sunk to this depth in order that pirates landing suddenly on the coast could see nothing of the traffic from a distance. But therein consisted their beauty, for the banks on either side were covered with luxuriant foliage, amongst which ferns and flowers struggled for existence, and the bushes and trees above in many places formed a natural and leafy arch over the road below. The surface of the roads was not very good, being naturally damp, as the drying influences of the wind and sun could scarcely penetrate to such sheltered positions, and in wet weather the mud had a tendency to accumulate; but we did not trouble ourselves about this as we walked steadily onwards. The roads were usually fairly straight, but went up and down hill regardless of gradients, though occasionally they were very crooked, and at cross-roads, in the absence of finger-posts or any one to direct us, it was easy to take a wrong turning. Still it was a real pleasure to walk along these beautiful Devonshire lanes.

In a Devonshire lane, as I trotted along

T’other day, much in want of a subject for song,

Thinks I to myself, I have hit on a strain—

Sure, marriage is much like a Devonshire lane.

In the first place ’tis long, and when once you are in it,

It holds you as fast as a cage does a linnet;

For howe’er rough and dirty the road may be found,

Drive forward you must, there is no turning round.

But though ’tis so long, it is not very wide,

For two are the most that together can ride;

And e’en then ’tis a chance but they sit in a pother.

And joke and cross and run foul of each other.

But thinks I too, the banks, within which we are pent,

With bud, blossom, berry, are richly besprent;

And the conjugal fence, which forbids us to roam.

Looks lovely, when deck’d with the comforts of home.

In the rock’s gloomy crevice the bright holly grows:

The ivy waves fresh o’er the withering rose,

And the evergreen love of a virtuous wife

Soothes the roughness of care—cheers the winter of life.

Then long be the journey, and narrow the way,

I’ll rejoice that I’ve seldom a turnpike to pay;

And whate’er others say, be the last to complain.

Though marriage is just like a Devonshire lane.

Late though it was in the year, there was still some autumn foliage on the trees and bushes and some few flowers and many ferns in sheltered places; we also had the golden furze or gorse to cheer us on our way, for an old saying in Devonshire runs—

When furze is out of bloom

Then love is out of tune,

which was equivalent to saying that love was never out of tune in Devonshire, for there were three varieties of furze in that county which bloomed in succession, so that there were always some blooms of that plant to be found. The variety we saw was that which begins to bloom in August and remains in full beauty till the end of January.

Beside the fire with toasted crabs

We sit, and love is there;

In merry Spring, with apple flowers

It flutters in the air.

At harvest, when we toss the sheaves,

Then love with them is toss’t;

At fall, when nipp’d and sear the leaves,

Un-nipp’d is love by frost.

Golden furze in bloom!

O golden furze in bloom!

When the furze is out of flower

Then love is out of tune.

Presently we arrived at Cockington, a secluded and ancient village, picturesque to a degree, with cottages built of red cobs and a quaint forge or smithy for the village blacksmith, all, including the entrance lodge to the squire’s park, being roofed or thatched with straw. Pretty gardens were attached to all of them, and everything looked so trim, clean, and neat that it was hard to realise that such a pretty and innocent-looking place had ever been the abode of smugglers or pirates; yet so it was, for hiding-holes existed there which belonged formerly to what were jocularly known as the early “Free Traders.” Near Anstey’s Cove, in Torbay, we had seen a small cave in the rocks known as the “Brandy Hole,” near which was the smuggler’s staircase. This was formed of occasional flights of roughly-hewn stone steps, up which in days gone by the kegs of brandy and gin and the bales of silk had been carried to the top of the cliffs and thence conveyed to Cockington and other villages in the neighbourhood where the smugglers’ dens existed.

Possibly Jack Rattenbury, the famous smuggler known as “the Rob Roy of the West,” escaped to Cockington when he was nearly caught by the crew of one of the King’s ships, for the search party were close on his heels when he saved himself by his agility in scaling the cliffs. But Cockington was peaceful enough when we visited it, and in the park, adorned with fine trees, stood the squire’s Hall, or Court, and the ivy-covered church. Cockington was mentioned in Domesday Book, and in 1361 a fair and a market were granted to Walter de Wodeland, usher to the Chamber of the Black Prince, who afterwards created him a knight, and it was probably about that time that the present church was built. The screen and pews and pulpit had formerly belonged to Tor Mohun church, and the font, with its finely carved cover and the other relics of wood, all gave us the impression of being extremely old, and as they were in the beginning. The Cary family were once the owners of the estate, and in the time of the Spanish Armada George Cary, who was afterwards knighted by Queen Elizabeth, with Sir John Gilbert, at that time the owner of Tor Abbey, took charge of the four hundred prisoners from the Spanish flagship Rosario while they were lodged in the grange of Tor Abbey.

From Cockington we walked on to Compton Castle, a fine old fortified house, one of the most interesting and best preserved remains of a castellated mansion in Devonshire. One small portion of it was inhabited, and all was covered with ivy, but we could easily trace the remains of the different apartments. It was formerly the home of the Gilbert family, of whom the best-known member was Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a celebrated navigator and mathematician of the sixteenth century, half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh, and knighted by Queen Elizabeth for his bravery in Ireland. Sir Humphrey afterwards made voyages of discovery, and added Newfoundland, our oldest colony, to the British Possessions, and went down with the Squirrel in a storm off the Azores. When his comrades saw him for the last time before he disappeared from their sight for ever in the mist and gloom of the evening, he held a Bible in his hand, and said cheerily, “Never mind, boys! we are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!”

We had a splendid walk across the hills, passing through Marldon, where the church was apparently the burial-place of the Gilbert family, of which it contained many records, including an effigy of Otho Gilbert, who was Sheriff of the County and who died in 1476. But the chief object of interest at Marldon appeared to be a six-barred gate called the Gallows Gate, which stood near the spot where the three parishes converged: Kingskerswell, Cockington, and Marldon; near this the culprits from those three places were formerly hanged. We looked for the gate in the direction pointed out to us, but failed to find it. Some people in the village thought its name of the Gallows Gate was derived from an incident which occurred there many years ago. A sheep-stealer had killed a sheep, and was carrying it home slung round his shoulders when he came to this gate. Finding it fastened, he was climbing over, when in the dark his foot slipped and the cord got across his neck. The weight of the carcase as it fell backwards, added to his own, caused him to be choked, so that he was literally hanged upon the gate instead of the gallows for what was in those days a capital offence.

After passing the Beacon Hill, we had very fine views over land and sea, extending to Dartmoor and Dartmouth, and with a downward gradient we soon came to Berry Pomeroy, the past and present owners of which had been associated with many events recorded in the history of England, from the time of William the Conqueror, who bestowed the manor, along with many others, on one of his followers named Ralph de Pomeroy. It was he who built the Castle, where the Pomeroys remained in possession until the year 1547, when it passed into the hands of the Seymour family, afterwards the Dukes of Somerset, in whose possession it still remained.

After the Pomeroys disappeared the first owner of the manor and castle was Edward Seymour, afterwards the haughty Lord Protector Somerset, who first rose in royal favour by the marriage of his eldest sister Jane Seymour to Henry VIII, and that monarch appointed him an executor under his will and a member of the Council on whom the duty devolved of guarding the powers of the Crown during the minority of his son and successor Edward VI, who only reigned six years, from 1547 to 1553; and Seymour’s father, Sir John, had accompanied King Henry VIII to his wars in France, and to the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

Henry VIII had great faith in his brother-in-law, and after the King’s death Seymour quickly gained ascendency over the remaining members of the Council, and was nominated Lord Treasurer of England, and created Earl of Somerset, Feb. 17, 1567; two days afterwards he obtained a grant of the office of Earl Marshal of England for life, and on the 12th of March following he procured a patent from the young King, who was his nephew, constituting himself the Protector of the Realm, an office altogether new to the Constitution and that gave him full regal power.

It was about that time that the English Reformation began, and the free circulation of the Bible was permitted. The Latin Mass was abolished, and the English Liturgy substituted, and 42 Articles of Faith were adopted by the English Protestants. Protector Somerset was a Protestant, and always took advice of Archbishop Cranmer, and care was taken that the young King was instructed in the Reformed Religion. King Henry VIII had arranged in his lifetime that Edward VI should marry Mary, the young Queen of Scotland, and Somerset raised an army and went to Scotland to secure her person: but after fighting a battle he only just managed to win, he found that the proposed union was not looked upon favourably in Scotland, and that the young Queen had been sent away to France for greater safety.

Meantime Somerset’s brother Thomas Seymour, High Admiral of England, had married Catherine Parr, widow of Henry VIII, without the knowledge of the Protector; and this, with the fierce opposition of the Roman Catholics, and of the Barons, whose taking possession of the common lands he had opposed, and the offence given to the population of London through demolishing an ancient parish church in the Strand there, so that he could build a fine mansion for himself, which still bears the name of Somerset House, led to the rapid decline of his influence, and after causing his brother to be beheaded he himself shared a similar fate.

Berry Pomeroy was a lovely spot, and the foliage was magnificent as we walked up to the castle and then to the village, while every now and then we came to a peep-hole through the dense mass of bushes and trees showing a lovely view beyond. The ruins of the castle were covered with ivy, moss, and creeping plants, while ferns and shrubs grew both inside and out, forming the most picturesque view of the kind that could be imagined. We were fortunate in securing the services of an enthusiastic and intelligent guide, who told us many stories of events that had taken place there, some of them of a sensational character. He showed us the precipice, then rapidly becoming obscured by bushes and trees, where the two brothers Pomeroy, with their horses, were dashed to pieces. The castle had been besieged for a long time, and when the two brothers found they could hold out no longer, rather than submit to the besiegers they sounded their horns in token of surrender, and, blindfolding their horses, mounted and rode over the battlements into the depths below! The horses seemed to know their danger, and struggled to turn back, but they were whipped and spurred on to meet the same dreadful fate as their masters. One look over the battlements was enough for us, as it was horrible to contemplate, but our guide seemed to delight in piling on the agony, as most awful deeds had been done in almost every part of the ruins, and he did not forget to tell us that ghosts haunted the place at night.

In a dismal room, or dungeon, under what was known as St. Margaret’s Tower, one sister had imprisoned another sister for years, because of jealousy, and in another place a mother had murdered her child. He also told us a story of an old Abbot who had been concerned in some dreadful crime, and had been punished by being buried alive. Three days were given him in which to repent, and on each day he had to witness the digging in unconsecrated ground of a portion of his grave. He groaned horribly, and refused to take any food, and on the third morning was so weak that he had to be carried to watch the completion of the grave in which he was to be buried the following day. On the fourth day, when the monks came in to dress him in his burial garments and placed him on the bier, he seemed to have recovered a little, and with a great effort he twisted himself and fell off. They lifted him on again, and four lay brothers carried him to the side of the deep grave. As he was lowered into the tomb a solemn dirge was sung by the monks, and prayers were offered for mercy on his sinful soul. The earth was being dropped slowly on him when a faint groan was heard; for a few moments the earth above him seemed convulsed a little, and then the grave was closed.

The ghost of the blood-stained Fontebrant and that of his assassin were amongst those that haunted Pomeroy Castle and its lonely surroundings, and cries and groans were occasionally heard in the village below from the shrieking shade of the guilty Eleanor, who murdered her uncle. At midnight she was said to fly from the fairies, who followed her with writhing serpents, their tongues glistening with poisonous venom and their pestiferous breath turning black everything with which they came in contact, and thus her soul was tortured as a punishment for her horrible deeds. Amongst the woods glided the pale ghosts of the Abbot Bertrand and the mother with her murdered child.

What a difference there is in guides, and especially when no “tips” are in sight! You go into a church, for instance, and are shown round in a general kind of a way and inquiries are answered briefly. As you leave the building you hand the caretaker a silver coin which he did not expect, and then, conscience-stricken, he immediately becomes loquacious and asks if you saw an object that he ought to have shown you, and it generally ends in your turning back and seeing double the objects of interest you saw before, and possibly those in the graveyard as well. Then there are others whose hearts are in their work, and who insist upon your seeing all there is to be seen and hearing the history or legends connected with the place. Such was our guide that morning; he was most enthusiastic when giving us his stories, but we did not accept his invitation to come some evening to see the ghosts, as we could not imagine a more lonely and “boggarty” spot at night than amongst the thick bushes and foliage of Berry Castle, very beautiful though it looked in the daylight; nor did we walk backwards three times round the trunk of the old “wishing tree,” and in the process wish for something that we might or might not get; but we rewarded our guide handsomely for his services.

We had a look in the old church, where there were numerous tombs of the Seymour family; but the screen chiefly attracted our attention. The projection of the rood-loft still remained on the top, adorned with fan tracery, and there was also the old door which led up to it. The lower panels had as usual been much damaged, but the carved figures could still be recognised, and some of the original colouring in gold, vermilion, green, and white remained. The figures were said to represent St. Matthew with his club, St. Philip with the spear, St. Stephen with stones in his chasuble, St. Jude with the boat, St. Matthias with the battle-axe, sword, and dagger, St. Mary Magdalene with the alabastrum, St. Barbara with the tower, St. Gudala with the lantern, and the four doctors of the Western Church. The ancient pulpit was of the same period as the screen, as were also the old-fashioned, straight-backed, oak pews.

THE SCREEN, BERRY POMEROY CHURCH

The vicarage, which was as usual near the church, must have been a very healthy place, for the Rev. John Prince, author of The Worthies of Devon, published in 1901, who died in 1723, was vicar there for forty-two years, and was succeeded by the Rev. Joseph Fox, who died in 1781, aged eighty-four, having been vicar for fifty-eight years. He was followed by the Rev. John Edwards, who was vicar for fifty-three years, and died in 1834 aged eighty-three. This list was very different from that we had seen at Hungerford, and we wondered whether a parallel for longevity in three successive vicars existed in all England, for they averaged fifty-one years’ service.

There were some rather large thatched cottages in Berry Pomeroy village, where Seymour, who was one of the first men of rank and fortune to join the Prince of Orange, met the future King after he had landed at Brixham on November 5th, 1688. A conference was held in these cottages, which were ever afterwards known as “Parliament Buildings,” that meeting forming William’s first Parliament. Seymour was at that time M.P. for Exeter, and was also acting as Governor of that city. When William arrived there four days afterwards, with an army of 15,000 men, he was awarded a very hearty reception, for he was looked upon as more of a deliverer than a conqueror.

It was only a short distance from Berry Pomeroy to Totnes, our next stage, and we were now to form our first acquaintance with the lovely valley of the River Dart, which we reached at the foot of the hill on which that picturesque and quaint old town was situated. Formerly the river had to be crossed by a rather difficult ford, but that had been done away with in the time of King John, and replaced by a narrow bridge of eight arches, which in its turn had been replaced in the time of William and Mary by a wider bridge of three arches with a toll-gate upon it, where all traffic except pedestrians had to contribute towards the cost of its erection. A short distance to the right after crossing the bridge was a monument to a former native of the town, to whom a sorrowful memory was attached; it had been erected by subscription, and was inscribed:

IN HONOR OF

WILLIAM JOHN WILLS

NATIVE OF TOTNES

THE FIRST WITH BURKE TO CROSS THE AUSTRALIAN CONTINENT

HE PERISHED IN RETURNING, 28 JUNE 1861

When the Australian Government offered a reward for an exploration of that Continent from north to south, Wills, at that time an assistant in the Observatory at Melbourne, volunteered his services along with Robert O’Hara Burke, an Irish police inspector. Burke was appointed leader of the expedition, consisting of thirteen persons, which started from Melbourne on August 20th, 1860, and in four months’ time reached the River Barco, to the east of Lake Eyre. Here it became necessary to divide the party: Burke took Wills with him, and two others, leaving the remainder at Cooper’s Creek to look after the stores and to wait there until Burke and his companions returned.

They reached Flinders River in February of the following year, but they found the country to be quite a desert, and provisions failed them. They were obliged to return, reaching Cooper’s Creek on April 21st, 1861. They arrived emaciated and exhausted, only to find that the others had given up all hope of seeing them again, and returned home. Burke and his companions struggled on for two months, but one by one they succumbed, until only one was left—a man named King. Fortunately he was found by some friendly natives, who treated him kindly, and was handed over to the search-party sent out to find the missing men. The bodies of Burke and Wills were also recovered, and buried with all honours at Melbourne, where a fine monument was erected to their memory.

Many of the early settlers in Australia were killed by the aborigines or bushmen, and a friend of ours who emigrated there from our native village many years ago was supposed to have been murdered by them. He wrote letters to his parents regularly for some years, and in his last letter told his friends that he was going farther into the bush in search of gold. For years they waited for further news, which never arrived; and he was never heard of again, to the great grief of his father and mother and other members of the family. It was a hazardous business exploring the wilds of Australia in those days, and it was quite possible that it was only the numerical strength of Burke’s party and of the search-party itself that saved them from a similar fate.

But many people attributed the misfortunes of the expedition to the number who took part in it, as there was a great prejudice against the number thirteen both at home and abroad. We had often, indeed, heard it said that if thirteen persons sat down to dinner together, one of their number would die! Some people thought that the legend had some connection with the Lord’s Supper, the twelve Apostles bringing the number up to thirteen, while others attributed it to a much earlier period. In Norse mythology, thirteen was considered unlucky, because at a banquet in Valhalla, the Scandinavian heaven, where twelve had sat down, Loki intruded and made the number thirteen, and Baldur was killed.

The Italians and even the Turks had strong objections to the number thirteen, and it never appeared on any of the doors on the streets of Paris, where, to avoid thirteen people sitting down to dinner, persons named Quatorziennes were invited to make a fourteenth:

Jamais on ne devrait

Se mettre a table treize,

Mais douze c’est parfait.

My brother thought the saying was only a catch, for it would be equally true to say all would die as one. He was quite prepared to run the risk of being the thirteenth to sit down to dinner, but that was when he felt very hungry, and even hinted that there might be no necessity for the others to sit down at all!

But we must return to Totnes and its bridge, and follow the long narrow street immediately before us named Fore Street until we reach “the Arch,” or East Gate. The old-fashioned houses to the right and left were a great attraction to my brother, who had strong antiquarian predilections, and when he saw the old church and castle, he began to talk of staying there for the rest of the day and I had some difficulty in getting him along. Fortunately, close at hand there was a quaint Elizabethan mansion doing duty as a refreshment house, with all manner of good things in the windows and the word “Beds” on a window in an upper storey. Here we called for refreshments, and got some coffee and some good things to eat, with some of the best Devonshire cream we had yet tasted. After an argument in which I pointed out the danger of jeopardising our twenty-five-mile average walk by staying there, as it was yet early in the forenoon, we settled matters in this way; we would leave our luggage in Totnes, walk round the town to the objects of greatest interest, then walk to Dartmouth and back, and stay the night on our return, thus following to some extent the example of Brutus, the earliest recorded visitor:

Here I stand and here I rest,

And this place shall be called Totnes.

There was no doubt about the antiquity of Totnes, for Geoffrey of Monmouth, the author of the famous old English Chronicle, a compilation from older authors, in his Historia Britonum, 1147, began his notes on Totnes not in the time of the Saxons nor even with the Roman Occupation, but with the visit of Brutus, hundreds of years before the Christian era. Brutus of Troy had a strange career. His mother died in giving him birth, and he accidentally shot his father with an arrow when out hunting. Banished from Italy, he took refuge in Greece, where it was said he married a daughter of the King, afterwards sailing to discover a new country. Arriving off our shores, he sailed up the River Dart until he could get no farther, and then landed at the foot of the hill where Totnes now stands. The stone on which he first set foot was ever afterwards known as Brutus’s stone, and was removed for safety near to the centre of the town; where for ages the mayor or other official gave out all royal proclamations from it, such as the accessions to the throne—the last before our visit having been that of her most gracious Majesty Queen Victoria.

The Charter of Totnes was dated 1205, the mayor claiming precedence over the Lord Mayor of London, for Totnes, if not the oldest, was one of the oldest boroughs in England. It was therefore not to be wondered at that the Corporation possessed many curios: amongst them were the original ring to which the bull was fastened when bull-baiting formed one of the pastimes in England; a very ancient wooden chest; the staves used by the constables in past generations; a curious arm-chair used by the town clerk; a list of mayors from the year 1377 to the present time; two original proclamations by Oliver Cromwell; many old placards of important events; an exceptionally fine fourteenth-century frieze; a water-pipe formed out of the trunk of an elm tree; the old stocks; and an engraving representing the arrival of William of Orange at Brixham.

There was a church at Totnes in the time of the Conquest, for it was mentioned in a charter by which “Judhel de Totnais,” the Norman Baron to whom the Conqueror gave the borough, granted the “Ecclesiam Sancte Marie de Toteneo” to the Benedictine Abbey at Angers; but the present church was built in 1432 by Bishop Lacy, who granted a forty-days’ indulgence for all who contributed to the work. His figure and coat-of-arms were still to be seen on the church tower, which was 120 feet high, with the words in raised stone letters, “I made the Tour.” There was also a figure of St. Loe, the patron Saint of artificers in brass and iron, who was shown in the act of shoeing a horse. The corporation appeared to have had control of the church, and in 1450 had erected the altar screen, which was perhaps the most striking object there, for after the restoration, which was in progress at the time of our visit, of nine stone screens in Devon churches, excepting that in Exeter Cathedral, it claimed to be the most beautiful.

In the church there was also an elaborate brass candelabrum for eighteen lights with this suitable inscription:

Thy Word is a Lantern to my Feet

And a light unto my Path.

Donum Dei et Deo

17th May 1701.

The corporation has also some property in the church in the shape of elaborately carved stalls erected in 1636; also an ancient Bible and Prayer Book handsomely bound for the use of the mayor, and presented April 12th, 1690, by the Honble. Lady Anne Seymour of Berry Pomeroy Castle, whose autograph the books contain; and in the Parvise Chamber attached to the church there were about 300 old books dating from 1518 to 1676, one a copy of Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World, published in 1634.

The carved stone pulpit, of the same date as the screen, had at one time been divided into Gothic panels, on which were shields designed to represent the twelve sons of Israel: Judah was represented by a lion couchant, Zebulon by a ship under sail, Issachar as a laden ass resting, and Dan as a serpent coiled with head erect, and so on according to the description given of each of the sons in the forty-ninth chapter of Genesis.

There were a number of monuments in the church, the principal being that of Christopher Blacall, who died in 1635. He was represented as kneeling down in the attitude of prayer, while below were shown his four wives, also kneeling.

The conductor showed us the very fine organ, which before being placed there had been exhibited at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851; and we also saw the key of the church door, which, as well as the lock, had been in use for quite four hundred years.

We then paid a hurried visit to the ruins of the old castle, which in the time of Henry VIII was described by Leland the antiquary as “The Castelle waul and the strong dungeon be maintained; but the logginges of the Castelle be cleane in ruine”; but about thirty years before our visit the Duke of Somerset, the representative of the Seymour family, laid out the grounds and made of them quite a nice garden, with a flight of steps of easy gradient leading to the top of the old Norman Keep, from which we had a fine view of the country between Dartmoor and the sea.

Totnes was supposed to have been the Roman “Ad Darium,” at the end of the Fosse Way, and was also the famous harbour of the Celts where the great Vortigern was overthrown by Ambrosius. As the seas were infested with pirates, ports were chosen well up the estuaries of rivers, often at the limit of the tides; and Totnes, to which point the Dart is still navigated, remained of importance from Saxon times, through the struggles with the Danes until the arrival of the Normans; after this it was gradually superseded by Dartmouth.

At Totnes, when we asked the way to Dartmouth, the people jocularly told us that the only direct way was by boat down the river; but our rules and regulations would not permit of our going that way, so we decided to keep as near to the river as we could on the outward journey and find an alternative route on our return. This was a good idea, but we found it very difficult to carry out in the former case, owing to the streams which the River Dart receives on both sides on its way towards the sea. Relieved of the weight of our luggage, we set off at a good speed across fields and through woods, travelling along lanes the banks of which were in places covered with ferns. In Cheshire we had plenty of bracken, but very few ferns, but here they flourished in many varieties. A gentleman whom we met rambling along the river bank told us there were about forty different kinds of ferns and what he called “fern allies” to be found in the lanes and meadows in Devonshire. He said it was also noted for fungi, in which he appeared to be more interested than in the ferns, telling us there were six or seven hundred varieties, some of them being very beautiful both in colour and form; but we never cared very much for these, as we thought them too much akin to poisonous toadstools. We asked him why the lanes in Devonshire were so much below the surface of the land, and he said they had been constructed in that way in very ancient times to hide the passage of cattle and produce belonging to the British from the sight of their Saxon oppressors. He complained strongly of the destruction of ferns by visitors from populous places, who thought they would grow in their gardens or back-yards, and carried the roots away with them to be planted in positions where they were sure to die. In later years, it was said, young ladies and curates advertised hampers of Devonshire ferns for sale to eke out their small incomes; and when this proved successful, regular dealers did the same, and devastated woods and lanes by rooting up the ferns and almost exterminating some of the rarer kinds; but when the County Councils were formed, this wholesale destruction was forbidden.

We had a fairly straight course along the river for two or three miles, and on our way called to see an enormous wych-elm tree in Sharpham Park, the branches of which were said to cover a quarter of an acre of ground. It was certainly an enormous tree, much the largest we had seen of that variety, for the stem was about sixteen feet in girth and the leading branches about eighty feet long and nine feet in circumference. The Hall stood on an eminence overlooking the river, with great woods surrounding it, and the windings of the river from this point looked like a number of meres or lakes, while the gardens and woods of Sharpham were second to none in the County of Devon. Near the woods we passed a small cottage, which seemed to be at the end of everywhere, and was known locally as the “World’s End.” The first watery obstruction we came to was where the River Harbourne entered the River Dart, and here we turned aside along what was known as the Bow Creek, walking in a go-as-you-please way through lovely wooded and rocky scenery until we reached a water-mill. We had seen several herons on our way, a rather scarce bird, and we were told there was a breeding-place for them at Sharpham, together with a very large rookery. We passed Cornworthy, where there was an old church and a prehistoric camp, and some ruins of a priory of Augustinian nuns which existed there in the fourteenth century; but we had no time to explore them, and hastened on to Dittisham, where we regained the bank of the River Dart. This was another of the places we had arrived at either too late or too early, for it was famous for its plums, which grew in abundance at both Higher and Lower Dittisham, the bloom on the trees there forming a lovely sight in spring. A great many plums known as damsons were grown in Cheshire, and in olden times were allowed to remain on the trees until the light frosts came in late September or early October, as it was considered that they had not attained their full flavour until then; but in later times as soon as they were black they were hurried off to market, for they would crush in packing if left until thoroughly ripe.

Dittisham was also noted for its cockles and shrimps. The river here widened until it assumed the appearance of a lake about two miles wide, and the steamboat which plied between Totnes and Dartmouth landed passengers at Dittisham. As it lay about half way between the two places, it formed a favourite resort for visitors coming either way, and tea and cockles or tea and shrimps or, at the right time, tea and damsons—might be obtained at almost any of the pleasant little cottages which bordered the river. These luxuries could be combined with a walk through lovely scenery or a climb up the Fire Beacon Hill, about 600 feet above sea-level; or rowing-boats could be had if required, and we were informed that many visitors stayed about there in the season.

Across the river were several notable places: Sandbridge to the left and Greenway to the right. At Sandbridge was born the famous navigator John Davis, who was the first to explore the Arctic regions. On June 7th, 1575, he left Dartmouth with two small barques—the Sunshine, 50 tons, carrying 23 men, and the Moonshine, 35 tons, and 19 men—and after many difficulties reached a passage between Greenland and North America, which was so narrowed between the ice that it was named Davis’ Straits. He made other voyages to the Arctic regions, and was said to have discovered Hudson’s Straits. Afterwards he sailed several times to the East Indies; but whilst returning from one of these expeditions was killed on December 27th, 1605, in a fight with some Malay pirates on the coast of Malacca.

Greenway House, on the other hand, was at one time the residence of those two remarkable half-brothers Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Sir Walter Raleigh, and it was there that Sir Walter planted the first potato ever grown in England, which he had brought from abroad. As he was the first to introduce tobacco, it was probably at Greenway that his servant coming in with a jug of beer, and seeing his master as he thought burning, threw it in his face—”to put his master out,” as he afterwards explained.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert appeared to have been a missionary as well as an explorer, for it was recorded that he “set out to discover the remote countries of America and to bring off those savages from their diabolical superstitions to the embracing of the Gospel,” which would probably account for his having a Bible in his hand when he went down with his ship—an event which in later years was immortalised by Longfellow:

Eastward from Campobello

Sir Humphrey Gilbert sailed;

Three days or more seaward he bore.

Then, alas! the land wind failed.

He sat upon the deck,

The Book was in his hand;

“Do not fear, Heaven is as near,”

He said, “by water as by land!”

Beyond Dittisham the river turned towards Dartmouth through a very narrow passage, with a dangerous rock near the centre, now called the Anchor Stone, which was covered at high water. It appeared, however, to have been used in former times to serve the purpose of the ducking-stool, for the men of Dartmouth and Dittisham brought scolds there and placed them on the rock at low water for immersion with the rising tide, whence it became known-as the “Scold’s Stone.” One hour on the stone was generally sufficient for a scolding woman, for she could see the approach of the water that would presently rise well above her waist, and very few chose to remain on the stone rather than repent, although of course it was open to them to do so.

After negotiating the intricacies of one other small creek, we entered the ancient town of Dartmouth highly delighted with our lovely tramp along the River Dart.

We were now in a nautical area, and could imagine the excitement that would be caused amongst the natives when the beacon fires warned them of the approach of the Spanish Armada, for Dartmouth was then regarded as a creek of Plymouth Harbour.

The great fleet invincible against us bore in vain

The richest spoils of Mexico, the stoutest hearts of Spain.

THE MOUTH OF THE DART FROM MOUNT BOONE.

Dartmouth is one of the most picturesquely situated towns in England, and the two castles, one on either side of the narrow and deep mouth of the Dart, added to the beauty of the scene and reminded us of the times when we were continually at war with our neighbours across the Channel. The castles were only small, but so were the ships that crossed the seas in those days, and they would no doubt be considered formidable fortresses then. At low tide the Dart at that point was never less than five yards deep, and in the dark it was an easy matter for a ship to pass through unobserved. To provide against this contingency, according to a document in the possession of the Corporation dating from the twenty-first year of the reign of King Edward IV, a grant of £30 per annum out of the Customs was made to the “Mayor, Bailiffs, and Burgesses of Dartmouth, who had begonne to make a strong and myghte Toure of lyme and stone adjoining the Castelle there,” and who were also to “fynde a cheyne sufficient in length and strength to streche and be laide over-thwarte or a travers the mouth of the haven of Dartmouth” from Dartmouth Castle to Kingswear Castle on the opposite bank to keep out all intruders. This “myghte cheyne” was raised across the entrance every night so that no ships could get through, and the groove through which it passed was still to be seen.

Dartmouth Castle stood low down on a point of land on the seashore, and had two towers, the circular one having been built in the time of Henry VIII. Immediately adjoining it was a very small church of a much earlier date than the castle, dedicated to St. Petrox, a British saint of the sixth century. Behind the castle and the church was a hill called Gallants’ Bower, formerly used as a beacon station, the hollow on the summit having been formed to protect the fire from the wind. This rock partly overhung the water and served to protect both the church and the castle. Kingswear Castle, on the opposite side of the water, was built in the fourteenth century, and had only one tower, the space between the two castles being known as the “Narrows.” They were intended to protect the entrance to the magnificent harbour inland; but there were other defences, as an Italian spy in 1599, soon after the time of the Spanish Armada, reported as follows:

Dartmouth is not walled—the mountains are its walls. Deep water is everywhere, and at the entrance five yards deep at low water. Bastion of earth at entrance with six or eight pieces of artillery; farther in is a castle with 24 pieces and 50 men, and then another earth bastion with six pieces.

The harbour was at one time large enough to hold the whole British navy, and was considered very safe, as the entrance could be so easily defended, but its only representative now appeared to be an enormous three-decker wooden ship, named the Britannia, used as a training-ship for naval officers. It seemed almost out of place there, and quite dwarfed the smaller boats in the harbour, one deck rising above another, and all painted black and white. We heard afterwards that the real Britannia, which carried the Admiral’s flag in the Black Sea early in the Crimean War, had been broken up in 1870, the year before our visit, having done duty at Dartmouth as a training-ship since 1863. The ship we now saw was in reality the Prince of Wales, also a three-decker, and the largest and last built of “England’s wooden walls,” carrying 128 guns. She had been brought round to Dartmouth in 1869 and rechristened Britannia, forming the fifth ship of that name in the British navy.

H.M.S. BRITANNIA AND HINDUSTANI AT THE MOUTH OF THE DART.

It was in that harbour that the ships were assembled in 1190 during the Crusades, to join Richard Coeur-de-Lion at Messina. In his absence Dartmouth was stormed by the French, and for two centuries alternate warlike visits were made to the sea-coasts of England and France.

In 1338 the Dartmouth sailors captured five French ships, and murdered all their crews except nine men; and in 1347, when the large armament sailed under Edward III to the siege of Calais, the people of Dartmouth, who in turn had suffered much from the French, contributed the large number of 31 ships and 757 mariners to the King’s Fleet, the largest number from any port, except Fowey and London.

In 1377 the town was partly burnt by the French, and in 1403 Dartmouth combined with Plymouth, and their ships ravaged the coasts of France, where, falling in with the French fleet, they destroyed and captured forty-one of the enemy.

In the following year, 1404, the French attempted to avenge themselves, and landed near Stoke Fleming, about three miles outside Dartmouth, with a view to attacking the town in the rear; but owing to the loquacity of one of the men connected with the enterprise the inhabitants were forewarned and prepared accordingly. Du Chatel, a Breton Knight, was the leader of the Expedition, and came over, as he said, “to exterminate the vipers”; but when he landed, matters turned out “otherwise than he had hoped,” for the Dartmouth men had dug a deep ditch near the seacoast, and 600 of them were strongly entrenched behind it, many with their wives, “who fought like wild cats.” They were armed with slings, with which they made such good practice that scores of the Bretons fell in the ditch, where the men finished them off, and the rest of the force retreated, leaving 400 dead and 200 prisoners in the hands of the English.

OLD HOUSES IN HIGHER STREET, DARTMOUTH

In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers called at Dartmouth with their ships Speedwell and Mayflower, as the captain of the Speedwell (who it was afterwards thought did not want to cross the Atlantic) complained that his ship needed repairs, but on examination she was pronounced seaworthy. The same difficulty occurred when they reached Plymouth, with the result that the Mayflower sailed alone from that port, carrying the Fathers to form a new empire of Englishmen in the New World.

We were delighted with the old towns on the south coast—so different from those we had seen on the west; they seemed to have borrowed some of their quaint semi-foreign architecture from those across the Channel. The town of Dartmouth was a quaint old place and one of the oldest boroughs in England. It contained, both in its main street and the narrow passages leading out of it, many old houses with projecting wooden beams ornamented with grotesque gargoyles and many other exquisite carvings in a good state of preservation. Like Totnes, the town possessed a “Butter Walk,” built early in the seventeenth century, where houses supported by granite pillars overhung the pavement. In one house there was a plaster ceiling designed to represent the Scriptural genealogy of our Saviour from Jesse to the Virgin Mary, and at each of the four corners appeared one of the Apostles: St. Matthew with the bull or ox, St. Luke with the eagle, St. Mark with the lion, and St. John with the attendant angel—-probably a copy of the Jesse stained-glass windows, in which Jesse is represented in a recumbent posture with a vine or tree rising out of his loins as described by Isaiah, xi. I: “And there shall come forth a Rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots.”

The churches in Dartmouth were well worth a visit. St. Saviour’s, built in 1372, contained an elaborately carved oak screen, one of the finest in the county and of singular beauty, erected in the fifteenth century. It was in perfect condition, and spread above the chancel in the form of a canopy supporting the rood-loft, with beautiful carving and painted figures in panels. The pulpit was of stone, richly carved and gilt, and showed the Tudor rose and portcullis, with the thistle, harp, and fleur-de-lys; there were also some seat-ends nicely carved and some old chandeliers dated 1701—the same date as the fine one we saw in the church at Totnes.

ST. SAVIOUR’S CHURCH, DARTMOUTH.

The chancel contained the tomb, dated 1394, of John Hawley, who died in 1408, and his two wives—Joan who died in 1394, and Alice who died in 1403. Hawley was a rich merchant, and in the war against France equipped at his own expense a fleet, which seemed to have been of good service to him, for in 1389 he captured thirty-four vessels from Rochelle, laden with 1,500 tons of wine. John Stow, a famous antiquary of the sixteenth century, mentioned this man in his Annals as “the merchant of Dartmouth who in 1390 waged war with the navies and ships of the ports of our own shores,” and “took 34 shippes laden with wyne to the sum of fifteen hundred tunnes,” so we considered Hawley must have been a pirate of the first degree.

There was a brass in the chancel with this inscription, the moral of which we had seen expressed in so many different forms elsewhere:

Behold thyselfe by me,

I was as thou art now:

And them in time shalt be

Even dust as I am now;

So doth this figure point to thee

The form and state of each degree.

ANCIENT DOOR IN ST. SAVIOUR’S CHURCH

The gallery at the west end was built in 1631, and there was a door in the church of the same date, but the ironwork on this was said to be two hundred years older, having probably been transferred to it from a former door. It was one of the most curious we had ever seen. Two animals which we took to be lions were impaled on a tree with roots, branches, and leaves. One lion was across the tree just under the top branches, and the other lion was across it at the bottom just above the roots, both standing with their heads to the right and facing the beholder; but the trunk of the tree seemed to have grown through each of their bodies, giving the impression that they were impaled upon it. The date of the woodwork (1631) was carved underneath the body of the lion at the top, the first figure in the date appearing to the left and the remaining three to the right, while the leaves on the tree resembled those of the oak. Whether the lions were connected in any way with those on the borough coat-of-arms we did not know, but this bore a lion on either side of it, the hinder portion of their bodies hanging over each side of an ancient boat and their faces being turned towards the spectator, while a crowned king, evidently meant for Richard Coeur-de-Lion, was sitting between them—the lions being intended to represent the Lions of Judah. The King was crowned, but above him, suspended over the boat, was a much larger crown, and underneath that and in the air to the left, but slightly above the King’s crown, was the Turkish Crescent, while in a similar position to the right was represented the Star of Jerusalem.

The original parish church of Dartmouth, on the outskirts of the town, contained two rather remarkable epitaphs:

Here lyeth buried the Bodie of Robert Holland who

Departed this life 1611 beinge of

The age of 54 years 5 months and odd dayes.

Here lies a breathless body and doth showe

What man is, when God claims, what man doth owe.

His soule a guest his body a trouble

His tyme an instant, and his breath a bubble.

Come Lord Jesus, come quickly.

The other was worded:

William Koope, of Little

Dartmouth dyed in Bilbao

January the 30th, 1666, in the 6

yeare of his abode there beinge

embalmed and put into a Leaden

Coffin, was, after Tenn Weekes

Tossinge on the seas, here

Below interred May ye 23

AO. DOM. 1667 Ætates svæ 35.

Thomas Newcomen, born at Dartmouth in 1663, was the first man to employ steam power in Cornish mines, and the real inventor of the steam engine. The first steamboat on the River Dart was named after him.

In the time of the Civil War Dartmouth was taken by the Royalists, who held it for a time, but later it was attacked from both land and sea by Fairfax, and surrendered to the Parliament. Immediately afterwards a rather strange event happened, as a French ship conveying despatches for the Royalists from the Queen, Lord Goring, and others, who were in France, entered the port, the captain being ignorant of the change that had just taken place. On hearing that the Parliament was in possession, he threw his despatches overboard. These were afterwards recovered and sent up to Parliament, where they were found to be of a very important nature—in fact, the discoveries made in them were said to have had some effect in deciding the fate of King Charles himself.

We had now to face our return journey to Totnes, so we fortified ourselves with a substantial tea, and then began our dark and lonely walk of twelve miles by the alternative route, as it was useless to attempt to find the other on a dark night. We had, however, become quite accustomed to this kind of thing, and though we went astray on one occasion and found ourselves in a deep and narrow road, we soon regained the hard road we had left. The thought of the lovely country we had seen that day, and the pretty places we had visited, cheered us on our way, and my brother said he should visit that neighbourhood again before long. I did not treat his remark seriously at the time, thinking it equivalent to the remarks in hotel books where visitors express their unfulfilled intention of coming again. But when on May 29th, 1873, a lovely day of sunshine, my brother departed with one of the handsomest girls in the village for what the newspapers described as “London and the South,” and when we received a letter informing us that they were both very well and very happy, and amusing themselves by watching the salmon shooting up the deep weir on the River Dart, and sailing in a small boat with a sail that could easily be worked with one hand, and had sailed along the river to Dartmouth and back, I was not surprised when I found that the postmark on the envelope was TOTNES.

In his letter to me on that occasion, he said he had received from his mother his “marching orders” for his next long journey; and although her letter is now old and the ink faded, the “orders” are still firmly fixed where that good old writer intended them to be, and, as my brother said, they deserved to be written in letters of gold:

My earnest desire is that you may both be happy, and that whatever you do may be to the glory of God and the good of your fellow-creatures, and that at the last you may be found with your lamps burning and your lights shining, waiting for the coming of the Lord!

(Distance walked thirty-one-miles.)

Tuesday, November 14th.

We had made good progress yesterday in consequence of not having to carry any luggage, but we had now to carry our belongings again as usual.

Totnes, we learned, was a walled town in the time of the Domesday Survey, and was again walled in 1265 by permission of Henry III. Of the four gates then existing, only two now remained, the North and the East; they were represented by archways, the gates themselves having long since disappeared. We passed under the Eastgate Archway, which supported a room in which were two carved heads said to represent King Henry VIII and his unfortunate wife Anne Boleyn; and with a parting glance at the ancient Butter Cross and piazzas, which reminded us somewhat of the ancient Rows in Chester, we passed out into the country wondering what our day’s walk would have in store for us.

We had thought of crossing over the centre of Dartmoor, but found it a much larger and wilder place than we had imagined, embracing over 100,000 acres of land and covering an area of about twenty-five square miles, while in the centre were many swamps or bogs, very dangerous, especially in wet or stormy weather. There were also many hills, or “tors,” rising to a considerable elevation above sea-level, and ranging from Haytor Rocks at 1,491 feet to High Willheys at 2,039 feet. Mists and clouds from the Atlantic were apt to sweep suddenly over the Moor and trap unwary travellers, so that many persons had perished in the bogs from time to time; and the clouds striking against the rocky tors caused the rainfall to be so heavy that the Moor had been named the “Land of Streams.” One of the bogs near the centre of the Moor was never dry, and formed a kind of shallow lake out of which rose five rivers, the Ockment or Okement, the Taw, the Tavy, the Teign, and the Dart, the last named and most important having given its name to the Moor. Besides these, the Avon, Erme, Meavy, Plym, and Yealm, with many tributary brooks, all rise in Dartmoor.

Devonshire was peculiar in having no forests except that of Dartmoor, which was devoid of trees except a small portion called Wistman’s Wood in the centre, but the trees in this looked so old and stunted as to make people suppose they had existed there since the time of the Conquest, while others thought they had originally formed one of the sacred groves connected with Druidical worship, since legend stated that living men had been nailed to them and their bodies left there to decay. The trees were stunted and only about double the height of an average-sized man, but with wide arms spread out at the top twisted and twined in all directions. Their roots were amongst great boulders, where adders’ nests abounded, so that it behoved visitors to be doubly careful in very hot weather. We could imagine the feelings of a solitary traveller in days gone by, with perhaps no living being but himself for miles, crossing this dismal moor and coming suddenly on the remains of one of these crucified sacrificial victims.

Not far from Wistman’s Wood was Crockern Tor, on the summit of which, according to the terms of an ancient charter, the Parliament dealing with the Stannary Courts was bound to assemble, the tables and seats of the members being hewn out of the solid rock or cut from great blocks of stone. The meetings at this particular spot of the Devon and Cornwall Stannary men continued until the middle of the eighteenth century. After the jury had been sworn and other preliminaries arranged, the Parliament adjourned to the Stannary towns, where its courts of record were opened for the administration of Justice among the “tinners,” the word Stannary being derived from the Latin “Stannum,” meaning tin.

Some of the tors still retained their Druidical names, such as Bel-Tor, Ham-Tor, Mis-Tor; and there were many remains of altars, logans, and cromlechs scattered over the moors, proving their great antiquity and pointing to the time when the priests of the Britons burned incense and offered human victims as sacrifices to Bel and Baal and to the Heavenly bodies.

There was another contingency to be considered in crossing Dartmoor in the direction we had intended—especially in the case of a solitary traveller journeying haphazard—and that was the huge prison built by the Government in the year 1808 on the opposite fringe of the Moor to accommodate prisoners taken during the French wars, and since converted into an ordinary convict settlement. It was seldom that a convict escaped, for it was very difficult to cross the Moor, and the prison dress was so well known all over the district; but such cases had occurred, and one of these runaways, to whom a little money and a change of raiment would have been acceptable, might have been a source of inconvenience, if not of danger, to any unprotected traveller, whom he could have compelled to change clothing.

We therefore decided to go round the Moor instead of over it, and visit the town of Plymouth, which otherwise we should not have seen.

The whole of Dartmoor was given by Edward III to his son the Black Prince, when he gave him the title of Duke of Cornwall after his victorious return from France, and it still belonged to the Duchy of Cornwall, and was the property of the Crown; but all the Moor was open and free to visitors, who could follow their own route in crossing it, though in places it was gradually being brought into cultivation, especially in the neighbourhood of the many valleys which in the course of ages had been formed by the rivers on their passage towards the sea. As our road for some miles passed along the fringe of the great Moor, and as the streams crossed it in a transverse direction, on our way to Plymouth we passed over six rivers, besides several considerable brooks, after leaving the River Dart at Totnes. These rivers were named the Harbourne, Avon, Lud, Erme, Yealm, and Plym, all flowing from Dartmoor; and although there was such a heavy rainfall on the uplands, it was said that no one born and bred thereon ever died of pulmonary consumption. The beauty of Dartmoor lay chiefly along its fringes, where ancient villages stood securely sheltered along the banks of these streams; but in their higher reaches were the remains of “hut circles” and prehistoric antiquities of the earliest settlers, and relics of Neolithic man were supposed to be more numerous than elsewhere in England.

There was no doubt in our minds that the earliest settlers were those who landed on the south coast, and in occupying the country they naturally chose positions where a good supply of water was available, both for themselves and their cattle. The greater the number of running streams, the greater would be the number of the settlers. Some of the wildest districts in these southern countries, where solitude now prevailed, bore evidence of having, at one time, been thickly populated.

We did not attempt to investigate any of these pretty valleys, as we were anxious to reach Plymouth early in order to explore that town, so the only divergence we made from the beaten track was when we came to Ivybridge, on the River Erme. The ivy of course flourished everywhere, but it was particularly prolific in some parts of Devon, and here it had not only covered the bridge, over which we crossed, but seemed inclined to invade the town, to which it had given its name. The townspeople had not then objected to its intrusion, perhaps because, being always green, it was considered to be an emblem of everlasting life—or was it because in Roman mythology it was sacred to Bacchus, the God of Wine? In Egyptian mythology the ivy was sacred to Osiris, the Judge of the Dead and potentate of the kingdom of ghosts; but in our minds it was associated with our old friend Charles Dickens, who had died in the previous year, and whom we had once heard reading selections from his own writings in his own inimitable way. His description of the ivy is well worth recording—not that he was a poet, but he once wrote a song for Charles Russell to sing, entitled “The Ivy Green “:

Oh! a dainty plant is the ivy green.

That creepeth o’er ruins old!

Of right choice food are its meals, I ween;

In its cell so lone and cold.

The wall must be crumbled, the stone decayed,

To pleasure his dainty whim,

And the mouldering dust that years have made

Is a dainty meal for him.

Creeping where no life is seen,

A rare old plant is the ivy green.

Fast he stealeth on, though he wears no wings.

And a staunch old heart hath he:

How closely he twineth, how tight he clings.

To his friend the huge oak tree;

And slyly he traileth along the ground,

And his leaves he gently waves

As he joyously hugs and crawleth around

The rich mould of dead men’s graves.

Creeping where no life is seen,

A rare old plant is the ivy green.

Whole ages have fled, and their works decayed,

And nations have scattered been;

But the stout old ivy shall never fade

From its hale and hearty green;

The brave old plant in its lonely days

Shall fatten upon the past,

For the stateliest building man can raise

Is the ivy’s food at last.

Creeping where no life is seen,

A rare old plant is the ivy green.

It is remarkable that the ivy never clings to a poisonous tree, but the trees to which it so “closely twineth and tightly clings” it very often kills, even “its friend the huge oak tree.”

Near the bridge we stayed at a refreshment house to replenish the inner man, and the people there persuaded us to ramble along the track of the River Erme to a spot which “every visitor went to see”; so leaving our luggage, we went as directed. We followed the footpath under the trees that lined the banks of the river, which rushed down from the moor above as if in a great hurry to meet us, and the miniature waterfalls formed in dashing over the rocks and boulders that impeded its progress looked very pretty. Occasionally it paused a little in its progress to form small pools in which were mirrored the luxuriant growth of moss and ferns sheltering beneath the branches of the trees; but it was soon away again to form similar pretty pictures on its way down the valley. We were pleased indeed that we had not missed this charming bit of scenery.

Emerging from the dell, we returned by a different route, and saw in the distance the village of Harford, where in the church a brass had been placed to the Prideaux family by a former Bishop of Worcester. This bishop was a native of that village, and was in a humble position when he applied for the post of parish clerk of a neighbouring village, where his application was declined. He afterwards went to work at Oxford, and while he was there made the acquaintance of a gentleman who recognised his great talents, and obtained admission for him to one of the colleges. He rose from one position to another until he became Bishop of Worcester, and in after life often remarked that if he had been appointed parish clerk he would never have become a bishop.

We recovered our luggage and walked quickly to Plymouth, where we arrived in good time, after an easy day’s walk. We had decided to stop there for the night and, after securing suitable apartments, went out into the town. The sight of so many people moving backwards and forwards had quite a bewildering effect upon us after walking through moors and rather sleepy towns for such a long period; but after being amongst the crowds for a time, we soon became accustomed to our altered surroundings. As a matter of course, our first visit was to the Plymouth Hoe, and our first thoughts were of the great Spanish Armada.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE.

From the picture in the possession of Sir T.F. Elliot Drake.

The position of England as the leading Protestant country, with the fact of the refusal of Queen Elizabeth when the King of Spain proposed marriage, made war between the two countries almost certain. Drake had also provoked hostilities, for he had sailed to the West Indies in 1587, and after defeating the Spaniards there had entered the Bay of Cadiz with thirty ships and destroyed 10,000 tons of shipping—an achievement which he described as “singeing the whiskers of the King of Spain.” In consequence of this Philip, King of Spain, declared war on Elizabeth, Queen of England, and raised a great army of ships to overwhelm the English.

It was on Friday, July 19, 1588, that Captain Thomas Fleming, in charge of the pinnace Golden Hind, ran into Plymouth Sound with the news that the Spanish Armada was off the Lizard. The English captains were playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe when Captain Fleming arrived in hot haste to inform them that when his ship was off the French coast they had seen the Spanish fleet approaching in the distance, and had put on all sail to bring the news. This was the more startling because the English still believed it to be refitting in its own ports and unlikely to come out that year. Great excitement prevailed among the captains; but Drake, who knew all that could be known of the Spanish ships, and their way of fighting, had no fear of the enemy, and looked upon them with contempt, coolly remarking that they had plenty of time to finish the game and thrash the Spaniards afterwards. The beacon fires were lighted during the night, and—

Swift to east and swift to west

The ghastly war-flame spread;

High on St. Michael’s Mount it shone,

It shone on Beachy Head.

Far on the deep the Spaniards saw

Along each southern shire

Cape beyond cape, in endless range

Those twinkling points of fire.