WE BEGIN OUR JOURNEY

Sept. 18 to 24. 1871

“Huna Inn” — Canisbay — Bucholie Castle — Keiss — Girnigoe — Sinclair — Noss Head — Wick — or ¶ Wick Harbour — Mid Clyth — Lybster — Dunbeath ¶ Berriedale — Braemore — Maidens Paps Mountain — Lord Galloway’s Hunting-box — Ord of Caithness — Helmsdale ¶ Loth — Brora — Dunrobin Castle — Golspie ¶ The Mound — Loch Buidhee — Bonar Bridge — Dornoch Firth — Half-way House [Aultnamain Inn] ¶ Novar — Cromarty Firth — Dingwall — Muir of Ord — Beauly — Bogroy Inn — Inverness ¶¶

NB. I am adding OS Maps to the Days travel to help bring the distance covered and waypoints they mention each day to life. I’m also adding in links where I can to websites which have more info about visiting these points of interest. This is a big project, not quite as epic an undertaking of that of my ancestors, but a work in progress, so do check back! Hilary 🙂

Monday, September 18th.

We rose early and walked along the beach to Duncansbay Head, or Rongisby as the old maps have it, gathering a few of those charming little shells called John o’Groat Buckies by the way. After walking round the site of John o’Groat’s house, we returned to our comfortable quarters at the Huna Inn for breakfast. John o’Groat seems to have acted with more wisdom than many entrusted with the affairs of a nation. When his sons quarrelled for precedence at his table, he consoled them with the promise that when the next family gathering took place the matter should be settled to the satisfaction of all. During the interval he built a house having eight sides, each with a door and window, with an octagonal table in the centre so that each of his eight sons could enter at his own door and sit at his own side or “head” of the table. By this arrangement—which reminded us of King Arthur’s use of his round table—he dispelled the animosity which previously prevailed. After breakfast, and in the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie, we made an entry in the famous Album with name and address, object of journey, and exact time of departure, and they promised to reserve a space beneath the entry to record the result, which was to be posted to them immediately we reached our journey’s end.

It was about half-past ten o’clock when we started on our long walk along a circuitous and unknown route from John o’Groat’s to Land’s End. Our host and hostess stood watching our departure and waving adieux until we disappeared in the distance. We were in high spirits, and soon reached the junction of roads where we turned to the left towards Wick. The first part of our walk was through the Parish of Canisbay, in the ancient records of which some reference is made to the more recent representatives of the Groat family, but as these were made two hundred years ago, they were now almost illegible. Our road lay through a wild moorland district with a few farms and cottages here and there, mainly occupied by fishermen. There were no fences to the fields or roads, and no bushes or trees, and the cattle were either herded or tied to stakes.

After passing through Canisbay, we arrived at the most northerly house in the Parish of Wick, formerly a public-house, and recognised as the half-way house between Wick and John o’Groat’s. We found it occupied as a farm by Mr. John Nicolson, and here we saw the skeleton of a whale doing duty as a garden fence. The dead whale, seventy feet in length, had been found drifting in the sea, and had been hauled ashore by the fishermen. Mr. Nicolson had an ingenious son, who showed us a working sun-dial in the garden in front of the house which he had constructed out of a portion of the backbone, and in the same bone he had also formed a curious contrivance by which he could tell the day of the month. He told us he was the only man that studied painting in the North, and invited us into the house, wherein several rooms he showed us some of his paintings, which were really excellent considering they were executed in ordinary wall paint. His mother informed us that he began to study drawing when he was ill with a slow fever, but not bed-fast. Two of the pictures, that of an old bachelor and a Scotch lassie, a servant, were very good indeed. We also saw a picture of an old woman, a local celebrity, about a hundred years old, which was considered to be an excellent likeness, and showed the old lady’s eyes so sunk in her head as to be scarcely visible. We considered that we had here found one of Nature’s artists, who would probably have made a name for himself if given the advantages so many have who lack the ability, for he certainly possessed both the imaginative faculty and no small degree of dexterity in execution. He pointed out to us the house of a farmer over the way who slept in the Parish of Wick and took his meals in that of Canisbay, the boundary being marked by a chimney in the centre of the roof. He also informed us that his brother accompanied Elihu Burritt, the American blacksmith, for some distance when he walked from London to John o’Groat’s.

We were now about eleven miles from Wick, and as Mr. Nicolson told us of an old castle we had missed, we turned back across the moors for about a mile and a half to view it. He warned us that we might see a man belonging to the neighbourhood who was partly insane, and who, roaming amongst the castle ruins, usually ran straight towards any strangers as if to do them injury; but if we met him we must not be afraid, as he was perfectly harmless. We had no desire to meet a madman, and luckily, although we kept a sharp look-out, we did not see him. We found the ruined castle resting on a rock overlooking the sea with the rolling waves dashing on its base below; it was connected with the mainland by a very narrow strip broken through in one place, and formerly crossed by a drawbridge. As this was no longer available, it was somewhat difficult to scale the embankment opposite; still we scrambled up and passed triumphantly through the archway into the ruins, not meeting with that resistance we fancied we should have done in the days of its daring owner. A portion only of the tower remained, as the other part had fallen about two years before our visit. The castle, so tradition stated, had been built about the year 1100 by one Buchollie, a famous pirate, who owned also another castle somewhere in the Orkneys. How men could carry on such an unholy occupation amidst such dangerous surroundings was a mystery to us.

On our return we again saw our friend Mr. Nicolson, who told us there were quite a number of castles in Caithness, as well as Pictish forts and Druidical circles, a large proportion of the castles lying along the coast we were traversing. He gave us the names of some of them, and told us that they materially enhanced the beauty of this rock-bound coast. He also described to us a point of the coast near Ackergill, which we should pass, where the rocks formed a remarkably perfect profile of the Great Duke of Wellington, though others spoke of it as a black giant. It could only be seen from the sea, but was marvellously correct and life-like, and of gigantic proportions.

Acting on Mr. Nicolson’s instructions, we proceeded along the beach to Keiss Castle, and ascended to its second storey by means of a rustic ladder. It was apparently of a more recent date than Buchollie, and a greater portion of it remained standing. A little to the west of it we saw another and more modern castle, one of the seats of the Duke of Portland, who, we were told, had never yet visited it. Before reaching the village of Keiss, we came to a small quay, where we stayed a short time watching the fishermen getting their smacks ready before sailing out to sea, and then we adjourned to the village inn, where we were provided with a first-class tea, for which we were quite ready. The people at the inn evidently did not think their business inconsistent with religion, for on the walls of the apartment where we had our tea were hanging two pictures of a religious character, and a motto “Offer unto God thanksgiving,” and between them a framed advertisement of “Edinburgh Ales”!

After tea we continued our journey until we came to the last house in the village of Keiss, a small cottage on the left-hand side of the road, and here we called to inspect a model of John o’Groat’s house, which had been built by a local stonemason, and exhibited at the great Exhibition in London in 1862. Its skilful builder became insane soon after he had finished it, and shortly afterwards died. It was quite a palatial model and much more handsome than its supposed original was ever likely to have been. It had eight doors with eight flights of steps leading up to them, and above were eight towers with watchmen on them, and inside the house was a table with eight sides made from wood said to have been from the original table in the house of Groat, and procured from one of his descendants. The model was accompanied by a ground plan and a print of the elevation taken from a photo by a local artist. There was no charge for admission or for looking at the model, but a donation left with the fatherless family was thankfully received.

We now walked for miles along the seashore over huge sand-hills with fine views of the herring-boats putting out to sea. We counted fifty-six in one fleet, and the number would have been far greater had not Noss Head intervened to obstruct our view, as many more went out that night from Wick, although the herring season was now nearly over. We passed Ackergill Tower, the residence of Sir George Dunbar, and about two miles farther on we came to two old castles quite near to each other, which were formerly the strongholds of the Earls of Caithness. They were named Girnigoe and Sinclair. Girnigoe was the oldest, and under the ruins of the keep was a dismal dungeon.

It was now getting dark, and not the pleasantest time to view old castles surrounded by black rocks with the moan of the sea as it invaded the chasms of the rocks on which they stood. Amongst these lonely ruins we spoke of the past, for had our visit been three centuries earlier, the dismal sounds from the sea below would have mingled with those from the unfortunate young man chained up in that loathsome dungeon, whose only light came from a small hole high up in the wall. Such was John, Master of Caithness, the eldest son of the fifth Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, who is said to have been imprisoned here because he had wooed and won the affections of the daughter of a neighbouring laird, marked out by his father, at that time a widower, for himself. He was confined in that old dungeon for more than six long years before death released him from his inhuman parent.

During his imprisonment John had three keepers appointed over him—Murdoch Roy and two brothers named Ingram and David Sinclair. Roy attended him regularly, and did all the menial work, as the other two keepers were kinsmen of the earl, his father, who had imprisoned him. Roy was sorry for the unfortunate nobleman, and arranged a plot to set him at liberty, which was unfortunately discovered by John’s brother William, who bore him no good will. William told his father, the earl, who immediately ordered Roy to be executed. The poor wretch was accordingly brought out and hanged on the common gibbet of the castle without a moment being allowed him to prepare for his final account.

Soon afterwards, in order to avenge the death of Roy, John, who was a man of great bodily strength and whose bad usage and long imprisonment had affected his mind, managed to seize his brother William on the occasion of his visit to the dungeon and strangle him. This only deepened the earl’s antipathy towards his unhappy son, and his keepers were encouraged to put him to death. The plan adopted was such as could only have entered the imagination of fiends, for they withheld food from their prisoner for the space of five days, and then set before him a piece of salt beef of which he ate voraciously. Soon after, when he called for water, they refused to give him any, and he died of raging thirst. Another account said they gave him brandy, of which he drank so copiously that he died raving mad. In any case, there is no doubt whatever that he was barbarously done to death.

Every castle along the seacoast had some story of cruelty connected with it, but the story of Girnigoe was perhaps the worst of all, and we were glad to get away from a place with such dismal associations.

About a hundred years after this sad event the Clan of the Campbells of Glenorchy declared war on the Sinclairs of Keiss, and marched into Caithness to meet them; but the Sinclairs instead of going out to meet them at the Ord of Caithness, a naturally fortified position, stayed at home, and the Campbells took up a strong position at Altimarloch, about two miles from Wick. The Sinclairs spent the night before the battle drinking and carousing, and then attacked the Campbells in the strong position they had taken up, with the result that the Sinclairs were routed and many of them perished.

They meet, they close in deadly strife,

But brief the bloody fray;

Before the Campbells’ furious charge

The Caithness ranks give way.

The shrieking mother wrung her hands,

The maiden tore her hair,

And all was lamentation loud,

And terror, and despair.

It was commonly said that the well-known quicksteps, “The Campbells are coming” and the “Braes of Glenorchy” obtained their names from this raid.

The Sinclairs of Keiss were a powerful and warlike family, and they soon regained their position. It was a pleasing contrast to note that in 1765 Sir William Sinclair of Keiss had laid aside his sword, embracing the views held by the Baptists, and after being baptized in London became the founder of that denomination in Caithness and a well-known preacher and writer of hymns.

In his younger days he was in the army, where he earned fame as an expert swordsman, his fame in that respect spreading throughout the countryside. Years after he had retired from the service, while sitting in his study one forenoon intently perusing a religious work, his valet announced the arrival of a stranger who wished to see him. The servant was ordered to show him into the apartment, and in stalked a strong muscular-looking man with a formidable Andrea Ferrara sword hanging by his side, and, making a low obeisance, he thus addressed the knight:

“Sir William, I hope you will pardon my intrusion. I am a native of England and a professional swordsman. In the course of my travels through Scotland, I have not yet met with a gentleman able to cope with me in the noble science of swordsmanship. Since I came to Caithness I have heard that you are an adept with my favourite weapon, and I have called to see if you would do me the honour to exchange a few passes with me just in the way of testing our respective abilities.”

Sir William was both amused and astonished at this extraordinary request, and replied that he had long ago thrown aside the sword, and, except in case of necessity, never intended to use it any more. But the stranger would take no denial, and earnestly insisted that he would favour him with a proof of his skill.

“Very well,” said Sir William, “to please you I shall do so,” and, rising and fetching his sword, he desired the stranger, who was an ugly-looking fellow, to draw and defend himself. After a pass or two Sir William, with a dexterous stroke, cut off a button from the vest of his opponent.

“Will that satisfy you,” inquired Sir William; “or shall I go a little deeper and draw blood?”

“Oh, I am perfectly satisfied,” said the other. “I find I have for once met a gentleman who knows how to handle his sword.”

In about half a mile after leaving the ruins of these old castles we saw the Noss Head Lighthouse, with its powerful light already flashing over the darkening seas, and we decided to visit it. We had to scale several fences, and when we got there we found we had arrived long after the authorised hours for the admission of visitors. We had therefore some difficulty in gaining an entrance, as the man whose attention we had attracted did not at first understand why we could not come again the next day. When we explained the nature of our journey, he kindly admitted us through the gate. The lighthouse and its surroundings were scrupulously clean, and if we had been Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Lighthouses, if such there be, we could not have done otherwise than report favourably of our visit. The attendants were very kind to us, one of them accompanying us to the top, and as the lighthouse was 175 feet high, we had a great number of steps to climb. We had never seen the interior of a lighthouse before, and were greatly interested in the wonderful mechanism by which the flashlight was worked. We were much impressed by the incalculable value of these national institutions, especially in such dangerous positions as we knew from experience prevailed on those stormy coasts. We were highly delighted with our novel adventure, and, after regaining the entrance, we walked briskly away; but it was quite dark before we had covered the three miles that separated the lighthouse from the fishery town of Wick. Here we procured suitable lodgings, and then hurried to the post office for the letters that waited us, which we were delighted to read, for it seemed ages since we left home.

(Distance walked twenty-five miles.)

Tuesday, September 19th.

We had our first experience of a herring breakfast, and were surprised to find how delicious they tasted when absolutely fresh. There was an old proverb in Wick: “When the herrings come in, the doctors go out!” which may indicate that these fish had some medicinal value; but more likely the saying referred to the period of plenty following that of want and starvation. We went down to the quay and had a talk with some of the fishermen whom we met returning from their midnight labours. They told us they had not caught many herrings that night, but that the season generally had been a good one, and they would have money enough to support themselves through the coming winter. There were about nine hundred boats in the district, and sometimes over a thousand, all employed in the fishing industry; each boat was worked by four men and one boy, using nets 850 yards long. The herrings appeared about the second week in August and remained until the end of September, but the whales swallowed barrels of them at one “jow.”

We called at the steamboat depot and found that our hampers of shells had already arrived, and would be sent forward on the St. Magnus; next we went to get our hair and beards trimmed by the Wick barber. He was a curious old gentleman and quite an orator, and even at that early hour had one customer in hand while another was waiting to be shaved, so we had of course to wait our turn. The man who was waiting began to express his impatience in rather strong language, but the barber was quite equal to the occasion, and in the course of a long and eloquent oration, while he was engaged with the customer he had in hand, he told him that when he came into a barber’s shop he should have the calmness of mind to look quietly around and note the sublimity of the place, which ought to be sufficient to enable him to overcome such signs of impatience as he had exhibited. We were quite sure that the barber’s customer did not understand one-half the big words addressed to him, but they had the desired effect, and he waited patiently until his turn came to be shaved. He was a dark-complexioned seafaring man, and had evidently just returned from a long sea voyage, as the beard on his chin was more like the bristles on a blacking-brush, and the operation of removing them more like mowing than shaving. When completed, the barber held out his hand for payment. The usual charge must have been a penny, for that was the coin he placed in the barber’s hand. But it was now the barber’s turn. Drawing himself up to his full height, with a dignified but scornful expression on his face, he pointed with his razor to the penny he held in his other hand, which remained open, and exclaimed fiercely, “This! for a month’s shave!” Another penny was immediately added, and his impatient customer quickly and quietly departed.

It was now our turn for beard and hair trimming, but we had been so much amused at some of the words used by the barber that, had it not been for his awe-inspiring look, the scissors he now held in his hand, and the razors that were so near to us, we should have failed to suppress our laughter. The fact was that the shop was the smallest barber’s establishment we had ever patronised, and the dingiest-looking little place imaginable, the only light being from a very small window at the back of the shop. To apply the words sublime and sublimity to a place like this was ludicrous in the extreme. It was before this window that we sat while our hair was being cut; but as only one side of the head could be operated upon at once, owing to the scanty light, we had to sit before it sideways, and then to reverse our position.

We have heard it said that every man’s hair has a stronger growth on one side of his head than the other, but whether this barber left more hair on the strong side or not we did not know. In any case, the difference between the two sides, both of hair and beard, after the barber’s operation was very noticeable. The only sublime thing about the shop was the barber himself, and possibly he thought of himself when speaking of its sublimity. He was a well-known character in Wick, and if his lot had been cast in a more expansive neighbourhood he might have filled a much higher position. He impressed us very much, and had we visited Wick again we should certainly have paid him a complimentary visit. We then purchased a few prints of the neighbourhood at Mr. Johnston’s shop, and were given some information concerning the herring industry. It appeared that this industry was formerly in the hands of the Dutch, who exploited the British coasts as well as their own, for the log of the Dutillet, the ship which brought Prince Charles Edward to Scotland in 1745, records that on August 25th it joined two Dutch men-of-war and a fleet of herring craft off Rongisby.

In the early part of the fourteenth century there arose a large demand for this kind of fish by Roman Catholics both in the British Isles and on the Continent. The fish deserted the Baltic and new herring fields were sought, while it became necessary to find some method of preserving them. The art of curing herrings was discovered by a Dutchman named Baukel. Such was the importance attached to this discovery that the Emperor Charles V caused a costly memorial to be erected over his grave at Biervlet. The trade remained in the hands of the Dutch for a long time, and the cured herrings were chiefly shipped to Stettin, and thence to Spain and other Roman Catholic countries, large profits being made. In 1749, however, a British Fishery Society was established, and a bounty of £50 offered on every ton of herrings caught. In 1803 an expert Dutchman was employed to superintend the growing industry, and from 1830 Wick took the lead in the herring industry, which in a few years’ time extended all round the coasts, the piles of herring-barrels along the quay at Wick making a sight worth seeing.

We had not gone far when we turned aside to visit the ruins of Wick Castle, which had been named by the sailors “The Auld Man o’Wick.” It was built like most of the others we had seen, on a small promontory protected by the sea on three sides, but there were two crevices in the rock up which the sea was rushing with terrific force. The rock on which its foundations rested we estimated to be about 150 feet high, and there was only a narrow strip of land connecting it with the mainland. The solitary tower that remained standing was about fifty feet high, and apparently broader at the top than at the bottom, being about ten or twelve yards in length and breadth, with the walls six or seven feet thick. The roar of the water was like the sound of distant thunder, lending a melancholy charm to the scene. It was from here that we obtained our first land view of those strange-looking hills in Caithness called by the sailors, from their resemblance to the breasts of a maiden, the Maiden’s Paps. An old man directed us the way to Lybster by what he called the King’s Highway, and looking back from this point we had a fine view of the town of Wick and its surroundings.

Taught by past experience, we had provided ourselves with a specially constructed apparatus for tea-making, with a flask to fit inside to carry milk, and this we used many times during our journey through the Highlands of Scotland. We also carried a reserve stock of provisions, since we were often likely to be far away from any human habitation. To-day was the first time we had occasion to make use of it, and we had our lunch not in the room of an inn, but sitting amongst the heather under the broad blue canopy of heaven. It was a gloriously fine day, but not a forerunner of a fine day on the morrow, as after events showed. We had purchased six eggs at a farmhouse, for which we were only charged fourpence, and with a half-pound of honey and an enormous oatmeal cake—real Scotch—we had a jovial little picnic and did not fare badly. We had many a laugh at the self-satisfied sublimity of our friend the barber, but the sublimity here was real, surrounded as we were by magnificent views of the distant hills, and through the clear air we could see the mountains on the other side of the Moray Firth probably fifty miles distant. Our road was very hilly, and devoid of fences or trees or other objects to obstruct our view, so much so that at one point we could see two milestones, the second before we reached the first.

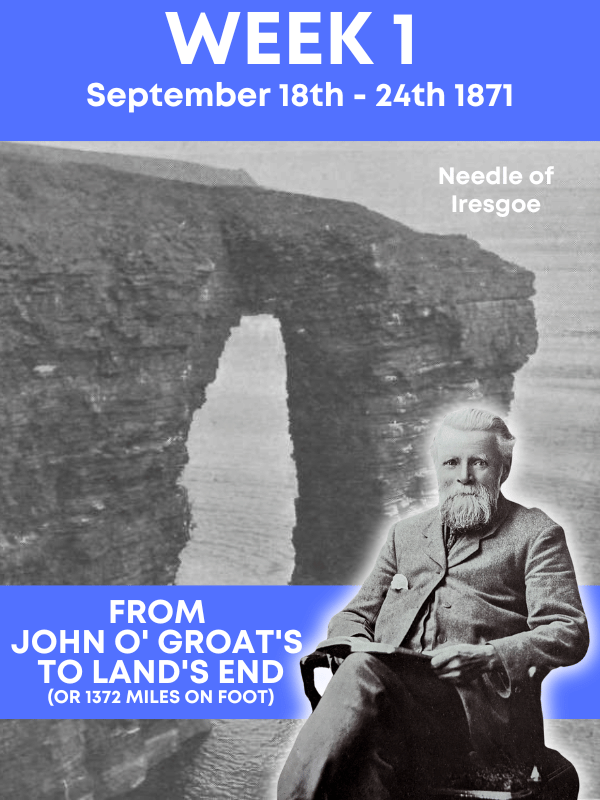

We passed Loch Hempriggs on the right of our road, with Iresgoe and its Needle on the seacoast to the left, also an old ruin which we were informed was a “tulloch,” but we did not know the meaning of the word. After passing the tenth milestone from Wick, we went to look at an ancient burial-ground which stood by the seaside about a field’s breadth from our road. The majority of the gravestones were very old, and whatever inscriptions they ever had were now worn away by age and weather; some were overgrown with grass and nettles, while in contrast to these stood some modern stones of polished granite. The inscriptions on these stones were worded differently from those places farther south. The familiar words “Sacred to the memory of” did not appear, and the phrasing appeared rather in the nature of a testimonial to the benevolence of the bereft. We copied two of the inscriptions:

ERECTED BY ROBERT WALLACE, MERCHANT, LYBSTER, TO THE MEMORY

OF HIS SPOUSE CHARLLOT SIMPSON WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE NOV. 21

1845 AGED 30 YEARS.

Lovely in Life.

PLACED BY JOHN SUTHERLAND, FISHERMAN, LYBSTER, IN MEMORY OF

HIS WIFE WILLIAMINIA POLSON WHO DIED 28TH MAY 1867 AGED 29

YEARS.

At Death still lovely.

In the yard we noticed a large number of loose stones and the remains of a wall which we supposed had been part of the kirk. The name of the village near here was Mid Clyth, and the ruins those of an old Roman Catholic chapel last used about four hundred years ago. Several attempts had been made to obtain power to remove the surplus stones, but our informant stated that although they had only about a dozen Romanists in the county, they were strong enough to prevent this being done, and it was the only burial-ground between there and Wick. He also told us that there were a thousand volunteers in Caithness.

The people in the North of Caithness in directing us on our way did not tell us to turn to right or left, but towards the points of the compass—say to the east or the west as the case might be, and then turn south for a given number of chains. This kind of information rather puzzled us, as we had no compass, nor did we know the length of a chain. It seemed to point back to a time when there were no roads at all in that county. We afterwards read that Pennant, the celebrated tourist, when visiting Caithness in 1769, wrote that at that time there was not a single cart, nor mile of road properly so called in the county. He described the whole district as little better than an “immense morass, with here and there some fruitful spots of oats and bere (barley), and much coarse grass, almost all wild, there being as yet very little cultivated.” And he goes on to add:

Here are neither barns nor granaries; the corn is thrashed out and preserved in the chaff in bykes, which are stacks in the shape of beehives thatched quite round. The tender sex (I blush for the Caithnessians) are the only animals of burden; they turn their patient backs to the dunghills and receive in their cassties or straw baskets as much as their lords and masters think fit to fling in with their pitchforks, and then trudge to the fields in droves.

A more modern writer, however, thought that Pennant must have been observant but not reflective, and wrote:

It is not on the sea coast that woman looks on man as lord and master. The fishing industry more than any other leads to great equality between the sexes. The man is away and the woman conducts all the family affairs on land. Home means all the comfort man can enjoy! His life is one persistent calling for self-reliance and independence and equally of obedience to command.

The relations Pennant quoted were not of servility, but of man assisting woman to do what she regarded as her natural work.

To inland folk like ourselves it was a strange sight to see so many women engaged in agricultural pursuits, but we realised that the men had been out fishing in the sea during the night and were now in bed. We saw one woman mowing oats with a scythe and another following her, gathering them up and binding them into sheaves, while several others were cutting down the oats with sickles; we saw others driving horses attached to carts. The children, or “bairns,” as they were called here, wore neither shoes nor stockings, except a few of the very young ones, and all the arable land was devoted to the culture of oats and turnips.

We passed through Lybster, which in Lancashire would only be regarded as a small village, but here was considered to be a town, as it could boast of a population of about eight hundred people. We made due note of our reaching what was acknowledged to be the second plantation of trees in the county; there were six only in the entire county of Caithness, and even a sight like this was cheery in these almost treeless regions.

An elderly and portly-looking gentleman who was on the road in front of us awaited our arrival, and as an introduction politely offered us a pinch of snuff out of his well-filled snuff-box, which we accepted. We tried to take it, but the application of a small portion to our noses caused us to sneeze so violently that the gentleman roared with laughter at our expense, and was evidently both surprised and amused at our distress. We were soon good friends, however, and he was as pleased with our company as we were with his, but we accepted no more pinches of snuff in Scotland. He had many inquiries to make about the method of farming in Cheshire and regarding the rotation of crops. We informed him that potatoes were the first crop following grass grown in our neighbourhood, followed by wheat in the next year, and oats and clover afterwards—the clover being cut for two years. “And how many years before wheat again?” he asked; but this question we could not answer, as we were not sufficiently advanced in agricultural knowledge to undergo a very serious examination from one who was evidently inclined to dive deeply into the subject. As we walked along, we noticed a stone on the slope of a mountain like those we had seen at Stenness in the Orkneys, but no halo of interest could be thrown around it by our friend, who simply said it had been there “since the world began.” Near Lybster we had a good view of the Ord of Caithness, a black-looking ridge of mountains terminating in the Maiden’s Paps, which were later to be associated with one of the most difficult and dangerous traverses we ever experienced.

The night was now coming on, and we hurried onwards, passing two old castles, one to the left and the other to the right of our road, and we noticed a gate, the posts of which had been formed from the rib-bones of a monster whale, forming an arch ornamented in the centre by a portion of the backbone of the same creature. In the dark the only objects we could distinguish were the rocks on the right and the lights of two lighthouses, one across Dornoch Firth and the other across Moray Firth. In another mile and a half after leaving the farmer, who had accompanied us for some miles and who, we afterwards learned, was an old bachelor, we were seated in the comfortable hotel at Dunbeath. The landlord was civil and communicative, and we sat talking to him about the great difference between Caithness and Cheshire, and the relative values of turf and coal. He informed us that there was very little coal consumed in the county of Caithness, as the English coal was dear and the Scotch coal bad, while the peat was of good quality, the darkest-looking being the richest and the best.

Our tea was now ready, and so were we, as we had walked fifteen miles since our lunch in the heather. We were ushered into the parlour, where we were delighted to find a Cheshire gentleman, who told us he had been out shooting, and intended to leave by the coach at two a.m. Hearing that two pedestrians had arrived, he had given up his bed, which he had engaged early in the day, and offered to rest on the sofa until the arrival of the mail-coach. We thanked him for his kind consideration, for we were tired and footsore. Who the gentleman was we did not discover; he knew Warrington and the neighbourhood, had visited Mr. Lyon of Appleton Hall near that town, and knew Mr. Patten of Bank Hall, who he said was fast getting “smoked out” of that neighbourhood. We retired early, and left him in full possession of the coffee-room and its sofa.

At two o’clock in the morning we were wakened by the loud blowing of a horn, which heralded the approach of the mail-coach, and in another minute the trampling of horses’ feet beneath our window announced its arrival. We rose hurriedly and rushed to the window, but in the hurry my brother dashed against a table, and down went something with a smash; on getting a light we found it was nothing more valuable than a water-bottle and glass, the broken pieces of which we carefully collected together, sopping up the water as best we could. We were in time to see our friend off on the coach, with three horses and an enormous light in front, which travelled from Thurso to Helmsdale, a distance of fifty-eight miles, at the rate of eight miles per hour.

(Distance walked twenty-one and a half miles.)

Wednesday, September 20th.

We rose early, and while waiting for our breakfast talked with an old habitué of the hotel, who, after drawing our attention to the weather, which had now changed for the worse, told us that the building of the new pier, as he called it, at Wick had been in progress for seven or eight years, but the sea there was the stormiest in Britain, and when the wind came one way the waves washed the pier down again, so that it was now no bigger than it was two years ago. He also told us he could remember the time when there was no mail-coach in that part of the country, the letters for that neighbourhood being sent to a man, a tailor by trade, who being often very busy, sent his wife to deliver them, so that Her Majesty’s mails were carried by a female!

Almost the last piece of advice given us before leaving home was, “Mind that you always get a good breakfast before starting out in a morning,” and fortunately we did not neglect it on this occasion, for it proved one of the worst day’s walks that we ever experienced. Helmsdale was our next stage, and a direct road led to it along the coast, a distance of sixteen miles. But my brother was a man of original ideas, and he had made up his mind that we should walk there by an inland route, and climb over the Maiden’s Paps mountain on our way.

The wind had increased considerably during the night, and the rain began to fall in torrents as we left the Dunbeath Inn, our mackintoshes and leggings again coming in useful. The question now arose whether we should adhere to our original proposal, or proceed to Helmsdale by the shortest route. Our host strongly advised us to keep to the main road, but we decided, in spite of our sore feet and the raging elements, to cross over the Maiden’s Paps. We therefore left the main road and followed a track which led towards the mountains and the wild moors. We had not gone very far when we met a disconsolate sportsman, accompanied by his gillies and dogs, who was retreating to the inn which he had left early in the morning. He explained to us how the rain would spoil his sport amongst the grouse, though he consoled himself by claiming that it had been one of the finest sporting seasons ever known in Caithness. As an illustration, he said that on the eighteenth day of September he had been out with a party who had shot forty-one and a half brace of grouse to each gun, besides other game. The average weight of grouse on the Scotch moors was twenty-five ounces, but those on the Caithness moors were heavier, and averaged twenty-five and a half ounces.

He was curious to know where we were going, and when we told him, he said we were attempting an impossible feat in such awful weather, and strongly advised us to return to the hotel, and try the journey on a finer day. We reflected that the fine weather had now apparently broken, and it would involve a loss of valuable time if we accepted his advice to wait for a finer day, so we pressed forwards for quite two hours across a dreary country, without a tree or a house or a human being to enliven us on our way. Fortunately the wind and rain were behind us, and we did not feel their pressure like our friend the sportsman, who was going in the opposite direction. At last we came to what might be called a village, where there were a few scattered houses and a burial-ground, but no kirk that we could see. Near here we crossed a stream known as Berriedale Water, and reached the last house, a farm, where our track practically ended. We knocked at the door, which was opened by the farmer himself, and his wife soon provided us with tea and oatmeal cake, which we enjoyed after our seven or eight-mile walk. The wind howled in the chimney and the rain rattled on the window-panes as we partook of our frugal meal, and we were inclined to exclaim with the poet whose name we knew not:

The day is cold and dark and dreary,

It rains, and the wind is never weary.

The people at the farm had come there from South Wales and did not know much about the country. All the information they could give us was that the place we had arrived at was named Braemore, and that on the other side of the hills, which they had never crossed themselves, there was a forest with no roads through it, and if we got there, we should have to make our way as best we could across the moors to Helmsdale. They showed us the best way to reach the foot of the mountain, but we found the going much worse than we anticipated, since the storm had now developed into one of great magnitude. Fortunately the wind was behind us, but the higher we ascended the stronger it became, and it fairly took our breath away even when we turned our heads towards it sideways, which made us realise how impossible it was for us to turn back, however much we might wish to do so; consequently we struggled onwards, occasionally taking advantage of the shelter of some projecting rock to recover our breathing—a very necessary proceeding, for as we approached the summit the rain became more like sleet, the wind was very cold, and the rocks were in a frozen and slippery condition. We were in great danger of being blown over and losing our lives, and as we could no longer walk upright in safety, we knelt down, not without a prayer to heaven as we continued on our way. Thus we crawled along upon our hands and knees over the smooth wind-swept summit of the Maiden’s Paps, now one immense surface of ice. The last bit was the worst of all, for here the raging elements struck us with full and uninterrupted force. We crossed this inches at a time, lying flat on the smooth rock with our faces downwards. Our feelings of thankfulness to the Almighty may be imagined when we finally reached the other side in safety.

Given a fine day we should have had a glorious view from this point, and, as it was, in spite of the rain we could see a long distance, but the prospect was far from encouraging. A great black rock, higher than that we had climbed, stood before us, with its summit hidden in the clouds, and a wide expanse of hills and moors, but not a house or tree so far as the eye could reach. This rather surprised us, as we expected the forest region to be covered with trees which would afford us some shelter on our farther way. We learned afterwards that the “forest” was but a name, the trees having disappeared ages ago from most of these forests in the northern regions of Scotland.

We were wet through to the skin and shivering with cold as we began to descend the other side of the Maiden’s Paps—a descent we found both difficult and dangerous. It looked an awful place below us—a wild amphitheatre of dreary hills and moors!

We had no compass to guide us, and in the absence of light from the sun we could not tell in what direction we were travelling, so with our backs towards the hills we had crossed, we made our way across the bog, now saturated with water. We could hear it gurgling under our feet at every stride, even when we could not see it, and occasionally we slipped into holes nearly knee-deep in water. After floundering in the bog for some time, and not knowing which way to turn, as we appeared to be surrounded with hills, we decided to try to walk against the wind which was blowing from the sea, for we knew that if we could reach the coast we should also reach the highway, which ran alongside it. But we soon had to give in, for we came to great rocks impossible for us to scale, so we had to abandon this direction and try another. The rain still continued, and our hands had now been bleached quite white with the rain beating on them, just like those of a washerwoman after a heavy day’s washing. We knew that the night would shortly be coming on, and the terrible thought of a dark night on the moors began to haunt us. If we could only have found a track we should not have cared, but we were now really LOST.

We were giving way to despair and beginning to think it might be a question of life or death when a bright thought suddenly struck us, and we wondered why we had not thought of it before. Why not follow the water, which would be sure to be running towards the sea? This idea inspired us with hope, and seemed to give us new life; but it was astonishing what a time elapsed before we found a running stream, for the water appeared to remain where it fell. At length we came to a small stream, the sight of which gave us renewed energy, and we followed it joyfully on its downward course. Presently we saw a few small bushes; then we came to a larger stream, and afterwards to a patch of grassland which clearly at one time had been under cultivation. At last we came to trees under which we could see some deer sheltering from the storm: by this time the stream had become a raging torrent. We stood watching the deer for a moment, when suddenly three fine stags rushed past us and dashed into the surging waters of the stream, which carried them down a considerable distance before they could land on its rocky bank on the other side. It was an exciting adventure, as the stags were so near us, and with their fine antlers presented an imposing appearance.

We now crossed over some heather in order to reach a small path which we could see alongside the swollen river. How pleased we were when we knew we were out of danger! It seemed to us like an escape from a terrible fate. We remembered how Mungo Park, when alone in the very heart of Africa, and in the midst of a great wilderness, derived consolation from very much smaller sources than the few trees which now cheered us on our way. The path became broader as we passed through the grounds of Lord Galloway’s hunting-box, and we soon reached the highway, where we crossed the boiling torrent rushing along with frightful rapidity on its way to the sea. The shades of night were coming on as we knocked at the door of the keeper’s cottage, and judge of our surprise when we were informed that, after walking from ten o’clock in the morning to six o’clock at night, we were only about six miles from Dunbeath, whence we had started that morning, and had still about ten miles to walk before we could reach Helmsdale.

We were almost famished with hunger, but we were lucky enough to secure a splendid tea at the keeper’s cottage. Fortunately for us the good lady of the house had provided a sumptuous repast for some sporting gentlemen she was expecting, but who had been prevented from coming owing to the storm. We kept no record of our gastronomical performances on this occasion, but we can safely state that of a whole rabbit very little remained, and the same remark would apply to a whole series of other delicacies which the keeper’s wife had so kindly and thoughtfully provided for her more distinguished but absent guests. We took the opportunity of drying some of our wet clothing, and before we finished our tea the keeper himself came in, to whom we related our adventures. Though accustomed to the broken regions and wild solitudes we had passed through, he was simply astounded that we had come over them safely, especially on such a day.

It was pitch dark when we left the keeper’s cottage, and he very kindly accompanied us until we reached the highroad in safety. The noise caused by the rushing waters of the rivers as they passed us on their way in frantic haste to the sea, now quite near us, and the roar of the sea itself as it dashed itself violently against the rocky coast, rendered conversation very difficult, but our companion gave us to understand that the road to Helmsdale was very hilly and lonely, and at one time was considered dangerous for strangers. Fortunately the surface was very good, and we found it much easier to walk upon than the wet heather we had passed over for so many miles. The black rocks which lined the road, the darkness of the night, and the noise from the sea as the great waves dashed and thundered on the rocks hundreds of feet below, might have terrified timid travellers, but they seemed nothing to us compared with our experience earlier in the day. The wind had moderated, but the rain continued to fall, and occasionally we were startled as we rounded one of the many bends in the road by coming suddenly on a burn swollen with the heavy rains, hurling itself like a cataract down the rocky sides of the hill, and rushing under the road beneath our feet in its noisy descent helter-skelter towards the sea.

We walked on as rapidly as the hilly nature of our road would permit, without seeing a house or human being, until we approached Helmsdale, when we were surprised by the sudden appearance of the stage-coach drawn by three horses and displaying its enormous red lamp in front. The driver suddenly pulled up his horses, for, as he said, he did not know “what the de’il it was coming in front”: he scarcely ever met any one on that road, and particularly on such an “awful” stormy night. We asked him how far we were from the town, and were delighted to hear it was only about two miles away. It was after ten o’clock when we arrived at Helmsdale, tired and footsore, but just in time to secure lodgings for the night at the Commercial Inn.

(Distance walked thirty miles.)

Thursday, September 21st.

Helmsdale was a pleasant little town inhabited chiefly by fishermen, but a place of some importance, for it had recently become the northern terminus of the railway. A book in the hotel, which we read while waiting for breakfast, gave us some interesting information about the road we had travelled along the night before, and from it we learned that the distance between Berriedale and Helmsdale was nine and a half miles, and that about half-way between these two places it passed the Ord of Caithness at an elevation of 1,200 feet above the sea-level, an “aclivity of granite past which no railway can be carried,” and the commencement of a long chain of mountains separating Caithness from Sutherland.

Formerly the road was carried along the edge of a tremendous range of precipices which overhung the sea in a fashion enough to frighten both man and beast, and was considered the most dangerous road in Scotland, so much so that when the Earl of Caithness or any other great landed proprietor travelled that way a troop of their tenants from the borders of Sutherland-shire assembled, and drew the carriage themselves across the hill, a distance of two miles, quadrupeds not being considered safe enough, as the least deviation would have resulted in a fall over the rocks into the sea below. This old road, which was too near the sea for modern traffic, was replaced by the present road in the year 1812. The old path, looked at from the neighbourhood of Helmsdale, had more the appearance of a sheep track than a road as it wound up the steep brow of the hill 300 or 400 feet above the rolling surge of the sea below, and was quite awe-inspiring even to look at, set among scenery of the most wild and savage character.

We had now cleared the county of Caithness, which, like Orkney and Shetland, was almost entirely devoid of trees. To our way of thinking a sprinkling of woods and copses would have much enhanced the wild beauty of the surroundings, but there was a difference of opinion or taste on this point as on everything else. A gentleman who had settled in America, and had had to clear away the trees from his holding, when he passed through Caithness on his way to John o’ Groat’s was continually ejaculating, “What a beautiful country!” “What a very beautiful country!” Some one who heard him remarked, “You can hardly call it a very beautiful country when there are no trees.” “Trees,” cried the Yankee; “that’s all stuff Caithness, I calculate, is the finest clearing I ever saw in my life!”

We had often wondered, by the way, how the Harbour Works at Wick would be affected by the great storms, and we were afterwards greatly interested when we read in a Scotch provincial newspaper the following telegrams:

TERRIFIC GALE AT WICK

THREATENED DESTRUCTION OF THE HARBOUR WORKS

From our Wick Correspondent

Wick, Wednesday, 12:50—A terrific storm is raging here to-day. It is a gale from the south-east, with an extraordinary surf which is making a complete break of the new Harbour Works, where a number of large stones have been dislodged and serious damage is threatened.

1:30 p.m.—The storm still continues. A large concrete block, weighing 300 tons, has been dislodged, and the whole building seems doomed unless the storm abates very soon.

These hours corresponded with the time we were crossing the Maiden’s Paps mountains, and we are not likely ever to forget the great danger we were in on that occasion.

We were rather backward in making a start on our journey to-day, for our feet were very sore; but we were advised to apply common soap to our stocking feet, from which we experienced great relief. As we left the town we saw some ruins, which we assumed were those of Helmsdale Castle, and we had now the company of the railway, which, like our road, hugged the seacoast for some miles. About two miles after leaving Helmsdale we sighted the first railway train we had seen since we left Aberdeen a fortnight before. Under ordinary conditions this might have passed unnoticed, but as we had been travelling through such wild country we looked upon it as a sign that we were approaching a part of the country which had communication with civilisation, other than that afforded by sea or mail-coach.

We now walked through the Parish of Loth, where in Glen Loth we were informed the last wolf in Scotland was killed, and about half a mile before reaching Brora we climbed over a stone fence to inspect the ruins of a Pictish castle standing between our road and the railway. The ruins were circular, but some of the walls had been built in a zig-zag form, and had originally contained passages and rooms, some of which still existed, but they looked so dark that we did not care to go inside them, though we were informed that about two years before our visit excavations had been made and several human skulls were discovered. The weather continued wet, and we passed through several showers on our way from Helmsdale to Brora, where, after a walk of twelve miles, we stayed for lunch, and it was again raining as we left there for Golspie.

At Brora we heard stories of wonderful fossils which were to be found in the rocks on the shore—shells and fish-scales and remains of bigger creatures—and of a bed of real coal. Certainly the rocks seemed to change their character hereabouts, which may account for the softening of the scenery and the contrast in agricultural pursuits in this region with those farther north. Here the appearance of the country gradually improved as we approached the woods and grounds and more cultivated regions surrounding the residence of the Duke of Sutherland.

“It was the finest building we had seen, not at all like the gloomy-looking castles, being more like a palace, with a fine display of oriel windows, battlements, steeples, and turrets.”

We came in sight of another Pictish castle, which we turned aside to visit; but by this time we had become quite familiar with the formation of these strange old structures, which were nearly all built after the same pattern, although some belonged to an earlier period than others, and the chambers in them were invariably dark and dismal. If these were used for the same purpose as similar ones we had seen in Shetland, where maidens of property and beauty were placed for protection from the “gallants” who roamed about the land in those days, the fair prisoners must have had a dismal time while incarcerated in these dungeon-like apartments. In these ruins, however, we saw some ancient utensils, or querns, supposed to have been used for crushing corn. They had been hollowed out in stone, and one of them had a well-worn stone inside it, but whether or no it was the remains of an ancient pestle used in crushing the corn we could not determine; it looked strangely like one.

The country hereabouts was of the most charming description, hilly and undulating rather than rugged, and we left the highway to walk along the seashore, where we passed the rifle and artillery ranges of the volunteers. We also saw the duke’s private pier extending towards the open sea, and from this point we had a fine view of Dunrobin Castle, the duke’s residence, which was the finest building we had seen, and not at all like the other gloomy-looking castles, being more like a palace. It is a happy blending of the German Schloss, the French château, and Scottish baronial architecture, with a fine display of oriel windows, battlements, turrets, and steeples, the great tower rising to a height of 135 feet above the garden terrace below. A vista of mountains and forests lay before any one privileged to ascend the tower. The view from the seashore was simply splendid, as from this point we could see, showing to great advantage, the lovely gardens, filled with beautiful shrubs and flowers of luxuriant growth, sloping upwards towards the castle, and the hills behind them, with their lower slopes covered with thousands of healthy-looking firs, pines, and some deciduous trees, while the bare moorland above formed a fine background. On the hill “Beinn-a-Bhragidh,” at a point 1,300 feet above sea-level, standing as if looking down on all, was a colossal monument erected to the memory of the duke’s grandfather, which could be seen many miles away. The duke must have been one of the largest landowners in Britain, as, in addition to other possessions, he owned the entire county of Sutherland, measuring about sixty miles long and fifty-six miles broad, so that when at home he could safely exclaim with Robinson Crusoe, “I am monarch of all I survey.”

The castle had an ancient foundation, for it was in 1097 the dun, or stronghold, of the second Robert of Sutherland, and the gardens have been famous from time immemorial. An extract from an old book written in 1630 reads, “The Erle of Sutherland made Dunrobin his speciall residence it being a house well-seated upon a mole hard by the sea, with fair orchards wher ther be pleasant gardens, planted with all kinds of froots, hearbs and flours used in this kingdom, and abundance of good saphorn, tobacco and rosemarie, the froot being excellent and cheeflie the pears and cherries.”

A most pleasing feature to our minds was the fact that the gardens were open to all comers, but as we heard that the duke was entertaining a distinguished company, including Lord Delamere of Vale Royal from our own county of Cheshire, we did not apply for permission to enter the grounds, and thus missed seeing the great Scotch thistle, the finest in all Scotland. This thistle was of the ordinary variety, but of colossal proportions, full seven feet high, or, as we afterwards saw it described, “a beautiful emblem of a war-like nation with his radious crown of rubies full seven feet high.” We had always looked upon the thistle as an inferior plant, and in Cheshire destroyed it in thousands, regarding it as only fit for food for donkeys, of which very few were kept in that county; but any one seeing this fine plant must have been greatly impressed by its appearance. The thistle has been the emblem of Scotland from very early times, and is supposed to have been adopted by the Scots after a victorious battle with the Danes, who on a dark night tried to attack them unawares. The Danes were creeping towards them silently, when one of them placed his bare foot on a thistle, which caused him to yell out with pain. This served as an alarm to the Scots, who at once fell upon the Danes and defeated them with great slaughter, and ever afterwards the thistle appeared as their national emblem, with the motto, Nemo me impune lacessit, or, “No one hurts me with impunity.”

Golspie was only a short distance away from the castle, and we were anxious to get there, as we expected letters from home, so we called at the post office first and got what letters had arrived, but another mail was expected. We asked where we could get a cup of coffee, and were directed to a fine reading-room opposite, where we adjourned to read our letters and reply to them with the accompaniment of coffee and light refreshments. The building had been erected by the Sutherland family, and was well patronised, and we wished that we might meet with similar places in other towns where we happened to call. Such as we found farther south did not appear to be appreciated by the class of people for whom they were chiefly intended. This may be accounted for by the fact that the working-class Scots were decidedly more highly educated than the English. We were not short of company, and we heard a lot of gossip, chiefly about what was going on at the castle.

On inquiring about our next stage, we were told that it involved a twenty-five-mile walk through an uninhabited country, without a village and with scarcely a house on the road. The distance we found afterwards had been exaggerated, but as it was still raining and the shades of evening were coming on, with our recent adventures still fresh in our minds and the letter my brother expected not having yet arrived, we agreed to spend the night at Golspie, resolving to make an early start on the following morning. We therefore went into the town to select suitable lodgings, again calling at the post office and leaving our address in the event of any letters coming by the expected mail, which the officials kindly consented to send to us, and after making a few purchases we retired to rest. We were just dozing off to sleep, when we were aroused by a knock at our chamber door, and a voice from without informed us that our further letters and a newspaper had arrived. We jumped out of bed, glad to receive additional news from the “old folks at home,” and our sleep was no less peaceful on that account.

(Distance walked eighteen miles.)

Friday, September 22nd.

We rose at seven o’clock, and left Golspie at eight en route for Bonar Bridge. As we passed the railway station we saw a huge traction engine, which we were informed belonged to the Duke of Sutherland, and was employed by him to draw wood and stone to the railway. About a mile after leaving the town we observed the first field of wheat since we had left John o’ Groat’s. The morning had turned out wet, so there was no one at work among the corn, but several machines there showed that agriculture received much attention. We met some children carrying milk, who in reply to our inquiry told us that the cows were milked three times each day—at six o’clock in the morning, one o’clock at noon, and eight o’clock at night—with the exception of the small Highland cows, which were only milked twice. As we were looking over the fields in the direction of the railway, we observed an engine with only one carriage attached proceeding along the line, which we thought must be the mail van, but we were told that it was the duke’s private train, and that he was driving the engine himself, the engine being named after his castle, “Dunrobin.” We learned that the whole railway belonged to him for many miles, and that he was quite an expert at engine driving.

About five miles after leaving Golspie we crossed what was known as “The Mound,” a bank thrown across what looked like an arm of the sea. It was upwards of half a mile long, and under the road were six arches to admit the passage of the tide as it ebbed and flowed. Here we turned off to the right along the hill road to Bonar Bridge, and visited what had been once a mansion, but was now nearly all fallen to the ground, very little remaining to tell of its former glory. What attracted us most was the site of the garden behind the house, where stood four great yew trees which must have been growing hundreds of years. They were growing in pairs, and in a position which suggested that the road had formerly passed between them.

Presently our way passed through a beautiful and romantic glen, with a fine stream swollen by the recent rains running alongside it. Had the weather been more favourable, we should have had a charming walk. The hills did not rise to any great elevation, but were nicely wooded down to the very edge of the stream, and the torrent, with its innumerable rapids and little falls, that met us as we travelled on our upward way, showed to the best advantage. In a few miles we came to a beautiful waterfall facing our road, and we climbed up the rocks to get a near view of it from a rustic bridge placed there for the purpose. A large projecting rock split the fall into the shape of a two-pronged fork, so that it appeared like a double waterfall, and looked very pretty. Another stream entered the river near the foot of the waterfall, but the fall of this appeared to have been artificially broken thirty or forty times on its downward course, forming the same number of small lochs, or ponds. We had a grand sight of these miniature lakes as they overflowed one into another until their waters joined the stream below.

We now left the trees behind us and, emerging into the open country, travelled many miles across the moors alongside Loch Buidhee, our only company being the sheep and the grouse. As we approached Bonar Bridge we observed a party of sportsmen on the moors. From the frequency of their fire we supposed they were having good sport; a horse with panniers on its back, which were fast being ladened with the fallen game, was following them at a respectful distance. Then we came to a few small houses, near which were large stacks of peat or turf, which was being carted away in three carts. We asked the driver of the first cart we overtook how far it was to Bonar Bridge, and he replied two miles. We made the same inquiry from the second, who said three miles, and the reply of the third was two and a half miles. As the distance between the first and the third drivers was only one hundred yards, their replies rather amused us. Still we found it quite far enough, for we passed through shower after shower.

Our eighteen-mile walk had given us a good idea of “Caledonia stern and wild,” and at the same time had developed in us an enormous appetite when by two o’clock we entered the hotel facing Bonar Bridge for our dinner. The bridge was a fine substantial iron structure of about 150 feet span, having a stone arching at either end, and was of great importance, as it connected main roads and did away with the ferry which once existed there. As we crossed the bridge we noticed two vessels from Sunderland discharging coals, and some fallen fir-trees lying on the side of the water apparently waiting shipment for colliery purposes, apt illustrations of the interchange of productions. There were many fine plantations of fir-trees near Bonar Bridge, and as we passed the railway station we saw a rather substantial building across the water which we were informed was the “Puirshoose,” or “Poor House.”

Observing a village school to the left of our road, we looked through the open door; but the room was empty, so we called at the residence of the schoolmaster adjoining to get some reliable information about our further way, We found him playing on a piano and very civil and obliging, and he advised us to stay for the night at what was known as the Half-way House, which we should find on the hill road to Dingwall, and so named because it was halfway between Bonar and Alness, and nine miles from Bonar. Our road for the first two miles was close along Dornoch Firth, and the fine plantations of trees afforded us some protection against the wind and rain; then we left the highway and turned to the right, along the hill road. After a steep ascent for more than a mile, we passed under a lofty elevation, and found ourselves once more amongst the heather-bells so dear to the heart of every true Scot.

At this point we could not help lingering awhile to view the magnificent scene below. What a gorgeous panorama! The wide expanse of water, the bridge we had lately crossed and the adjoining small village, the fine plantations of trees, the duke’s monument rising above the woods at Golspie, were all visible, but obscured in places by the drifting showers. If the “Clerk of the Weather” had granted us sunshine instead of rain, we should have had a glorious prospect not soon to be forgotten. But we had still three miles to walk, or, as the people in the north style it, to travel, before we could reach the Half-Way House, when we met a solitary pedestrian, who as soon as he saw us coming sat down on a stone and awaited us until we got within speaking distance, when he began to talk to us. He was the Inspector of Roads, and had been walking first in one direction and then in the other during the whole of the day. He said he liked to speak to everybody he saw, as the roads were so very lonely in his district. He informed us that the Half-Way House was a comfortable place, and we could not do better than stay there for the night.

We were glad when we reached the end of our nine-mile walk, as the day had been very rough and stormy. As it was the third in succession of the same character, we did not care how soon the weather took a turn for the better. The Half-Way House stood in a deserted and lonely position on the moor some little distance from the road, without another house being visible for miles, and quite isolated from the outer world. We entered the farmyard, where we saw the mistress busy amongst the pigs, two dogs barking at us in a very threatening manner. We walked into the kitchen, the sole occupant of which was a “bairn,” who was quite naked, and whom we could just see behind a maiden of clothes drying before the fire. The mistress soon followed us into the house, and in reply to our query as to whether we could be accommodated for the night said, “I will see,” and invited us into the parlour, a room containing two beds and sundry chairs and tables. The floor in the kitchen was formed of clay, the parlour had a boarded floor, and the mantelpiece and roof were of very old wood, but there was neither firegrate nor fire.

After we had waited there a short time, the mistress again made her appearance, with a shovel full of red-hot peat, so, although she had not given us a decided answer as to whether we could stay the night or not, we considered that silence gave consent, especially when seconded by the arrival of the welcome fire.

“You surely must have missed your train!” she said; but when we told her that we were pedestrian tourists, or, as my brother described it, “on a walking expedition,” she looked surprised.

When she entered the room again we were sorting out our letters and papers, and she said, “You surely must be sappers!” We had some difficulty in making her understand the object of our journey, as she could not see how we could be walking for pleasure in such bad weather.

We found the peat made a very hot fire and did good service in helping to dry our wet clothing. We wanted some hot milk and bread for supper, which she was very reluctant to supply, as milk was extremely scarce on the moors, but as a special favour she robbed the remainder of the family to comply with our wishes. The wind howled outside, but we heeded it not, for we were comfortably housed before a blazing peat fire which gave out a considerable amount of heat. We lit one of our ozokerite candles, of which we carried a supply to be prepared for emergencies, and read our home newspaper, The Warrington Guardian, which was sent to us weekly, until supper-time arrived, and then we were surprised by our hostess bringing in an enormous bowl, apparently an ancient punch bowl, large enough to wash ourselves in, filled with hot milk and bread, along with two large wooden spoons. Armed with these, we both sat down with the punch-bowl between us, hungry enough and greedy enough to compete with one another as to which should devour the most. Which won would be difficult to say, but nothing remained except the bowl and the spoons and our extended selves.

We had walked twenty-seven miles, and it must have been weather such as we had experienced that inspired the poet to exclaim:

The west wind blows and brings rough weather,

The east brings cold and wet together,

The south wind blows and brings much rain,

The north wind blows it back again!

The beds were placed end to end, so that our feet came together, with a wooden fixture between the two beds to act as the dividing line. Needless to say we slept soundly, giving orders to be wakened early in the morning.

(Distance walked twenty-seven miles.)

Saturday, September 23rd.

We were awakened at six o’clock in the morning, and after a good breakfast we left the Half-Way House (later the “Aultnamain Inn”), and well pleased we were with the way the landlady had catered for our hungry requirements. We could see the sea in the distance, and as we resumed our march across the moors we were often alarmed suddenly by the harsh and disagreeable cries of the startled grouse as they rose hurriedly from the sides of our path, sounding almost exactly like “Go back! —go back!” We were, however, obliged to “Go forward,” and that fairly quickly, as we were already a few miles behind our contemplated average of twenty-five miles per day. We determined to make the loss good, and if possible to secure a slight margin to our credit, so we set out intending to reach Inverness that night if possible. In spite, therefore, of the orders given in such loud and unpleasant tones by the grouse, we advanced quickly onwards and left those birds to rejoice the heart of any sportsman who might follow.

Cromarty Firth was clearly visible as we left the moors, and we could distinguish what we thought was Cromarty itself, with its whitewashed houses, celebrated as the birthplace of the great geologist, Hugh Miller, of whom we had heard so much in the Orkneys. The original cause of the whitewashing of the houses in Cromarty was said to have been the result of an offer made by a former candidate for Parliamentary honours, who offered to whitewash any of the houses. As nearly all the free and independent electors accepted his offer, it was said that Cromarty came out of the Election of 1826 cleaner than any other place in Scotland, notwithstanding the fact that it happened in an age when parliamentarian representation generally went to the highest bidder.

We crossed the Strathrory River, and leaving the hills to our right found ourselves in quite a different kind of country, a veritable land of woods, where immense plantations of fir-trees covered the hills as far as the eye could reach, sufficient, apparently, to make up for the deficiency in Caithness and Sutherland in that respect, for we were now in the county of Ross and Cromarty.

Shortly afterwards we crossed over the River Alness. The country we now passed through was highly cultivated and very productive, containing some large farms, where every appearance of prosperity prevailed, and the tall chimneys in the rear of each spoke of the common use of coal. The breeding of cattle seemed to be carried on extensively; we saw one large herd assembled in a field adjoining our road, and were amused at a conversational passage of arms between the farmer and two cattle-dealers who were trying to do business, each side endeavouring to get the better of the other. It was not quite a war to the knife, but the fight between those Scots was like razor trying to cut razor, and we wished we had time to stay and hear how it ended.

Arriving at Novar, where there was a nice little railway station, we passed on to the village inn, and called for a second breakfast, which we thoroughly enjoyed after our twelve-mile walk. Here we heard that snow had fallen on one of the adjacent hills during the early hours of the morning, but it was now fine, and fortunately continued to be so during the whole of the day.

Our next stage was Dingwall, the chief town in the county of Ross, and at the extreme end of the Cromarty Firth, which was only six miles distant. We had a lovely walk to that town, very different from the lonely moors we had traversed earlier in the day, as our road now lay along the very edge of the Cromarty Firth, while the luxuriant foliage of the trees on the other side of our road almost formed an arch over our way. The water of the Firth was about two miles broad all the way to Dingwall, and the background formed by the wooded hills beyond the Firth made up a very fine picture. We had been fully prepared to find Dingwall a very pretty place, and in that we were not disappointed.

The great object of interest as we entered this miniature county town was a lofty monument fifty or sixty feet high,[Footnote: This monument has since been swept away.] which stood in a separate enclosure near a graveyard attached to a church. It was evidently very old, and leaning several points from the perpendicular, and was bound together almost to the top with bands of iron crossed in all directions to keep it from failing. A very curious legend was attached to it. It was erected to some steward named Roderick Mackenzie, who had been connected with the Cromarty estate many years ago, and who appeared to have resided at Kintail, being known as the Tutor of Kintail. He acted as administrator of the Mackenzie estates during the minority of his nephew, the grandfather of the first Earl of Cromarty, and was said to have been a man of much ability and considerable culture for the times in which he lived. At the same time he was a man of strong personality though of evil repute in the Gaelic-speaking districts, as the following couplet still current among the common people showed:

The three worst things in Scotland–

Mists in the dog-days, frost in May, and the Tutor of Kintail.

The story went that the tutor had a quarrel with a woman who appeared to have been quite as strong-minded as himself. She was a dairymaid in Strathconon with whom he had an agreement to supply him with a stone of cheese for every horn of milk given by each cow per day. For some reason the weight of cheese on one occasion happened to be light, and this so enraged the tutor that he drove her from the Strath. Unfortunately for him the dairymaid was a poetess, and she gave vent to her sorrow in verse, in which it may be assumed the tutor came in for much abuse. When she obtained another situation at the foot of Ben Wyvis, the far-reaching and powerful hand of the tutor drove her from there also; so at length she settled in the Clan Ranald Country in Barrisdale, on the shores of Loch Hourn on the west coast of Inverness-shire, a place at that time famous for shell-fish, where she might have dwelt in peace had she mastered the weakness of her sex for demanding the last word; but she burst forth once more in song, and the tutor came in for another scathing:

Though from Strathconon with its cream you’ve driven me,

And from Wyvis with its curds and cheese;

While billow beats on shore you cannot drive me

From the shell-fish of fair Barrisdale.

These stanzas came to the ear of the tutor, who wrote to Macdonald of Barrisdale demanding that he should plough up the beach, and when this had been done there were no longer any shell-fish to be found there.

The dairymaid vowed to be even with the tutor, and threatened to desecrate his grave. When he heard of the threat, in order to prevent its execution he built this strange monument, and instead of being buried beneath it he was said to have been buried near the summit; but the woman was not to be out-done, for after the tutor’s funeral she climbed to the top of the pinnacle and kept her vow to micturate there!