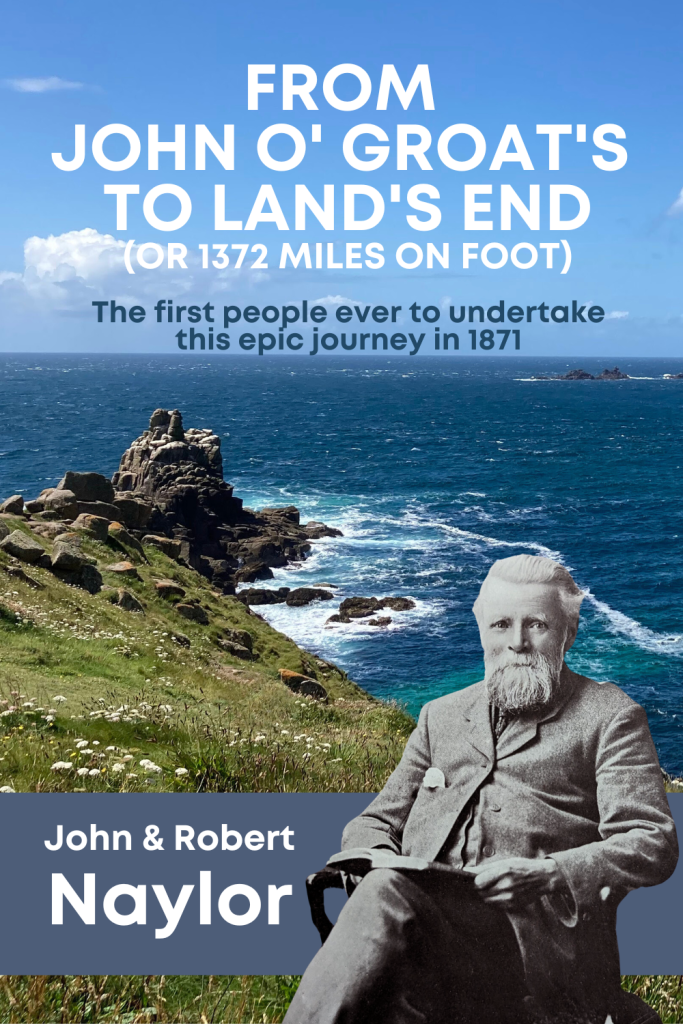

FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) My Great Great Grandfather, John Naylor and his brother Robert where the first people to walk from From John O Groat’s to Lands End in 1871. Read the book in full for free here on http://www.nearlyuphill.co.uk in chapters or download their 660 page book here – FROM JOHN O’ GROAT’S TO LAND’S END (OR 1372 MILES ON FOOT) All words are written by them and all pictures are taken from the original book which was written in 1916 by John Naylor.

FOURTH WEEK’S JOURNEY

Oct. 9 to Oct. 15.

Craigmillar — Rosslyn — Glencorse — Penicuik — Edleston — Cringletie — Peebles ¶ River Tweed — Horsburgh — Innerleithen — Traquair — Elibank Castle — Galashiels — Abbotsford — Melrose — Lilliesleaf ¶ Teviot Dale — Hassendean — Minto — Hawick — Goldielands Tower — Branxholm Tower — Teviothead — Caerlanrig — Mosspaul Inn — Langholm — Gilnockie Tower — Canonbie Colliery ¶ River Esk — “Cross Keys Inn” — Scotch Dyke — Longtown ¶ Solway Moss — River Sark — Springfield — Gretna Green — Todhills — Kingstown — Carlisle — Wigton — Aspatria ¶ Maryport — Cockermouth — Bassenthwaite Lake — Portinscale — Keswick ¶¶

Monday, October 9th

There were some streets in Edinburgh called wynds, and it was in one of these, the College Wynd, that Sir Walter Scott was born in the year 1771. It seemed a strange coincidence that the great Dr. Samuel Johnson should have visited the city in the same year, and have been conducted by Boswell and Principal Robertson to inspect the college along that same wynd when the future Sir Walter Scott was only about two years old. We had not yet ventured to explore one of these ancient wynds, as they appeared to us like private passages between two rows of tall houses. As we could not see the other end, we looked upon them as traps for the unwary, but we mustered up our courage and decided to explore one of them before leaving the town. We therefore rose early and selected one of an antiquated appearance, but we must confess to a feeling of some apprehension in entering it, as the houses on each side were of six to eight storeys high, and so lofty that they appeared almost to touch each other at the top. To make matters worse for us, there were a number of poles projecting from the windows high above our track, for use on washing days, when clothes were hung upon them to dry. We had not gone very far, when my brother drew my attention to two women whose heads appeared through opposite windows in the upper storeys, and who were talking to each other across the wynd. On our approach we heard one of them call to the other in a mischievous tone of voice, “See! there’s twa mair comin’!” We were rather nervous already, so we beat an ignominious retreat, not knowing what might be coming on our devoted heads if we proceeded farther. In the event of hostilities the two ladies were so high up in the buildings, which were probably let in flats, that we should never have been able to find them, and, like the stray sheep in the Pass of St. Ninians, we might never have been found ourselves. We were probably taken for a pair of sporting young medical students instead of grave searchers after wisdom and truth. We therefore returned to our hotel for the early breakfast that was waiting for us, and left Edinburgh at 8.10 a.m. on our way towards Peebles.

We journeyed along an upward gradient with a view of Craigmillar Castle to our left, obtaining on our way a magnificent view of the fine city we had left behind us, with its castle, and the more lofty elevation known as Arthur’s Seat, from which portions of twelve counties might be seen. It was a curiously shaped hill with ribs and bones crossing in various directions, which geologists tell us are undoubted remains of an old volcano. It certainly was a very active one, if one can judge by the quantity of debris it threw out. There was an old saying, especially interesting to ladies, that if you washed your face at sunrise on May 1st, with dew collected off the top of Arthur’s Seat, you would be beautiful for ever. We were either too late or too soon, as it was now October 9th, and as we had a lot to see on that day, with not overmuch time to see it in, we left the dew to the ladies, feeling certain, however, that they would be more likely to find it there in October than on May Day. When we had walked about five miles, we turned off the main road to visit the pretty village of Rosslyn, or Roslin, with its three great attractions: the chapel, the castle, and the dell. We found it surrounded by woods and watered by a very pretty reach of the River Esk, and as full of history as almost any place in Scotland.

The unique chapel was the great object of interest. The guide informed us that it was founded in 1446 by William St. Clair, who also built the castle, in which he resided in princely splendour. He must have been a person of very great importance, for he had titles enough even to weary a Spaniard, being Prince of Orkney, Duke of Oldenburg, Earl of Caithness and Stratherne, Lord St. Clair, Lord Liddlesdale, Lord Admiral of the Scottish Seas, Lord Chief Justice of Scotland, Lord Warden of the three Marches, Baron of Roslin, Knight of the Cockle, and High Chancellor, Chamberlain, and Lieutenant of Scotland!

The lords of Rosslyn were buried in their complete armour beneath the chapel floor up to the year 1650, but afterwards in coffins. Sir Walter Scott refers to them in his “Lay of the Last Minstrel” thus:—

There are twenty of Rosslyn’s Barons bold

Lie buried within that proud Chapelle.

ROSSLYN CHAPEL—THE “MASTER AND ‘PRENTICE PILLARS”

There were more carvings in Rosslyn Chapel than in any place of equal size that we saw in all our wanderings, finely executed, and with every small detail beautifully finished and exquisitely carved. Foliage, flowers, and ferns abounded, and religious allegories, such as the Seven Acts of Mercy, the Seven Deadly Sins, the Dance of Death, and many scenes from the Scriptures; it was thought that the original idea had been to represent a Bible in stone. The great object of interest was the magnificently carved pillar known as the “‘Prentice Pillar,” and in the chapel were two carved heads, each of them showing a deep scar on the right temple. To these, as well as the pillar, a melancholy memory was attached, from which it appeared that the master mason received orders that this pillar should be of exquisite workmanship and design. Fearing his inability to carry out his instructions, he went abroad to Rome to see what designs he could find for its execution. While he was away his apprentice had a dream in which he saw a most beautiful column, and, setting to work at once to carry out the design of his dream, finished the pillar, a perfect marvel of workmanship. When his master returned and found the pillar completed, he was so envious and enraged at the success of his apprentice that he struck him on the head with his mallet with such force that he killed him on the spot, a crime for which he was afterwards executed.

We passed on to the castle across a very narrow bridge over a ravine, but we did not find much there except a modern-looking house built with some of the old stones, under which were four dungeons. Rosslyn was associated with scenes rendered famous by Bruce and Wallace, Queen Mary and Rizzio, Robert III and Queen Annabella Drummond, by Comyn and Fraser, and by the St. Clairs, as well as by legendary stories of the Laird of Gilmorton Grange, who set fire to the house in which were his beautiful daughter and her lover, the guilty abbot, so that both of them were burnt to death, and of the Lady of Woodhouselee, a white-robed, restless spectre, who appeared with her infant in her arms. Then there was the triple battle between the Scots and the English, in which the Scots were victorious:

Three triumphs in a day!

Three hosts subdued by one!

Three armies scattered like the spray,

Beneath one vernal sun.

Here, too, was the inn, now the caretaker’s house, visited by Dr. Johnson and Boswell in 1773, the poet Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy in 1803, while some of the many other celebrities who called from time to time had left their signatures on the window-panes. Burns and his friend Nasmyth the artist breakfasted there on one occasion, and Burns was so pleased with the catering that he rewarded the landlady by scratching on a pewter plate the two following verses:

My blessings on you, sonsie wife,

I ne’er was here before;

You’ve gien us walth for horn and knife—

Nae heart could wish for more.

Heaven keep you free from care and strife.

Till far ayont four score;

And while I toddle on through life,

I’ll ne’er gang bye your door.

Rosslyn at one time was a quiet place and only thought of in Edinburgh when an explosion was heard at the Rosslyn gunpowder works. But many more visitors appeared after Sir Walter Scott raised it to eminence by his famous “Lay” and his ballad of “Rosabelle”:

Seem’d all on fire that chapel proud.

Where Rosslyn’s chiefs uncoffin’d lie.

Hawthornden was quite near where stood Ben Jonson’s sycamore, and Drummond’s Halls, and Cyprus Grove, but we had no time to see the caves where Sir Alexander Ramsay had such hairbreadth escapes. About the end of the year 1618 Ben Jonson, then Poet Laureate of England, walked from London to Edinburgh to visit his friend Taylor, the Thames waterman, commonly known as the Water Poet, who at that time was at Leith. In the January following he called to see the poet Drummond of Hawthornden, who was more frequently called by the name of the place where he lived than by his own. He found him sitting in front of his house, and as he approached Drummond welcomed him with the poetical salutation:

“Welcome! welcome! Royal Ben,”

to which Jonson responded,

“Thank ye, thank ye, Hawthornden.”

The poet Drummond was born in 1585, and died in 1649, his end being hastened by grief at the execution of Charles I. A relative erected a monument to his memory in 1784, to which the poet Young added the following lines:

O sacred solitude, divine retreat,

Choice of the prudent, envy of the great!

By the pure stream, or in the waving shade

I court fair Wisdom, that celestial maid;

Here from the ways of men, laid safe ashore,

I smile to hear the distant tempest roar;

Here, blest with health, with business unperplex’d,

This life I relish, and secure the next.

Rosslyn Glen was a lovely place, almost like a fairy scene, and we wondered if Burns had it in his mind when he wrote:

Their groves of sweet myrtle let foreign lands reckon,

Where bright-beaming summers exalt the perfume;

Far dearer to me yon lone glen of green bracken,

Wi’ the burn stealing under the long yellow broom.

We walked very quietly and quickly past the gunpowder works, lest conversation might cause an explosion that would put an end to our walking expedition and ourselves at the same time, and regained the highway at a point about seven miles from Edinburgh. Presently we came to the Glencorse Barracks, some portions of which adjoined our road, and, judging from the dress and speech of the solitary sentinel who was pacing to and fro in front of the entrance, we concluded that a regiment of Highlanders must be stationed there. He informed us that in the time of the French Wars some of the prisoners were employed in making Scotch banknotes at a mill close by, and that portions of the barracks were still used for prisoners, deserters, and the like. Passing on to Pennicuick, we crossed a stream that flowed from the direction of the Pentland Hills, and were informed that no less than seven paper mills were worked by that stream within a distance of five miles. Here we saw a monument which commemorated the interment of 309 French prisoners who died during the years 1811 to 1814, a list of their names being still in existence. This apparently large death-rate could not have been due to the unhealthiness of the Glencorse Barracks, where they were confined, for it was by repute one of the healthiest in the kingdom, the road being 600 feet or more above sea-level, and the district generally, including Pennicuick, considered a desirable health-resort for persons suffering from pulmonary complaints. We stayed a short time here for refreshments, and outside the town we came in contact with two young men who were travelling a mile or two on our way, with whom we joined company. We were giving them an outline of our journey and they were relating to us their version of the massacre of Glencoe, when suddenly a pretty little squirrel crossed our path and ran into a wood opposite. This caused the massacre story to be ended abruptly and roused the bloodthirsty instinct of the two Scots, who at once began to throw stones at it with murderous intent. We watched the battle as the squirrel jumped from branch to branch and passed from one tree to another until it reached one of rather large dimensions. At this stage our friends’ ammunition, which they had gathered hastily from the road, became exhausted, and we saw the squirrel looking at them from behind the trunk of the tree as they went to gather another supply. Before they were again ready for action the squirrel disappeared. We were pleased that it escaped, for our companions were good shots. They explained to us that squirrels were difficult animals to kill with a stone, unless they were hit under the throat. Stone-throwing was quite a common practice for country boys in Scotland, and many of them became so expert that they could hit small objects at a considerable distance. We were fairly good hands at it ourselves. It was rather a cruel sport, but loose stones were always plentiful on the roads—for the surfaces were not rolled, as in later years—and small animals, such as dogs and cats and all kinds of birds, were tempting targets. Dogs were the greatest sufferers, as they were more aggressive on the roads, and as my brother had once been bitten by one it was woe to the dog that came within his reach. Such was the accuracy acquired in the art of stone-throwing at these animals, that even stooping down in the road and pretending to lift a stone often caused the most savage dog to retreat quickly. We parted from the two Scots without asking them to finish their story of Glencoe, as the details were already fixed in our memories. They told us our road skirted a moor which extended for forty-seven miles or nearly as far as Glasgow, but we did not see much of the moor as we travelled in a different direction.

“JOUGS” AT A CHURCH, PEEBLESSHIRE.

We passed through Edleston, where the church was dedicated to St. Mungo, reminding us of Mungo Park, the famous African traveller, and, strangely enough, it appeared we were not far away from where he was born. In the churchyard here was a tombstone to the memory of four ministers named Robertson, who followed each other in a direct line extending to 160 years. There was also to be seen the ancient “Jougs,” or iron rings in which the necks of criminals were enclosed and fastened to a wall or post or tree. About three miles before reaching Peebles we came to the Mansion of Cringletie, the residence of the Wolfe-Murray family. The name of Wolfe had been adopted because one of the Murrays greatly distinguished himself at the Battle of Quebec, and on the lawn in front of the house was a cannon on which the following words had been engraved:

His Majesty’s Ship Royal George of 108 guns, sunk at Spithead 29th August 1782. This gun, a 32 pounder, part of the armament of the Royal George, was fished up from the wreck of that ship by Mr. Deans, the zealous and enterprising Diver, on the 15th November 1836, and was presented by the Master-General and Board of Ordnance to General Durham of Largo, the elder Brother of Sir Philip Charles Henderson Durham, Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Military Order of the Bath, Knight Commander of the Most Ancient Military Order of Merit of France, Admiral of the White Squadron of Her Majesty’s Fleet, and Commander-in-Chief of the Port of Portsmouth, 1836.

Sir Philip was serving as a lieutenant in the Royal George, and was actually on duty as officer of the watch upon deck when the awful catastrophe took place. He was providentially and miraculously saved, but nearly 900 persons perished, amongst them the brave Admiral Kempenfelt, whose flag went down with the ship.

The wreck of the Royal George was the most awful disaster that had hitherto happened to the Royal Navy. William Cowper the poet, as soon as the sad news was brought to him, wrote a solemn poem entitled “The Loss of the Royal George,” from which it seems that Admiral Kempenfelt was in his cabin when the great ship suddenly foundered.

His sword was in its sheath,

His fingers held the pen,

When Kempenfelt went down

With twice four hundred men.

Toll for the brave!

Brave Kempenfelt is gone:

His last sea-fight is fought,

His work of glory done.

Toll for the brave!

The brave that are no more.

All sunk beneath the wave.

Fast by their native shore!

It was nearly dark when we entered the town of Peebles, where we called at the post office for letters, and experienced some difficulty at first in obtaining lodgings, seeing that it was the night before the Hiring Fair. We went first to the Temperance Hotel, but all the beds had been taken down to make room for the great company they expected on the morrow; eventually we found good accommodation at the “Cross Keys Inn,” formerly the residence of a country laird.

We had seen notices posted about the town informing the public that, by order of the Magistrates, who saw the evil of intoxicating drinks, refreshments were to be provided the following day at the Town Hall. The Good Templars had also issued a notice that they were having a tea-party, for which of course we could not stay.

We found Peebles a most interesting place, and the neighbourhood immediately surrounding it was full of history. The site on which our hotel had been built was that of the hostelage belonging to the Abbey of Arbroath in 1317, the monks granting the hostelage to William Maceon, a burgess of Peebles, on condition that he would give to them, and their attorneys, honest lodging whenever business brought them to that town. He was to let them have the use of the hall, with tables and trestles, also the use of the spence (pantry) and buttery, sleeping chambers, a decent kitchen, and stables, and to provide them with the best candles of Paris, with rushes for the floor and salt for the table. In later times it was the town house of Williamson of Cardrona, and in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries became one of the principal inns, especially for those who, like ourselves, were travelling from the north, and was conducted by a family named Ritchie. Sir Walter Scott, who at that time resided quite near, frequented the house, which in his day was called the “Yett,” and we were shown the room he sat in. Miss Ritchie, the landlady in Scott’s day, who died in 1841, was the prototype of “Meg Dobs,” the inn being the “Cleikum Inn” of his novel St. Ronan’s Well.

THE CHURCH AND MONASTERY OF THE HOLY CROSS, PEEBLES, AD 1261.

There was a St. Mungo’s Well in Peebles, and Mungo Park was intimately associated with the town. He was born at Foulshiels, Yarrow, in the same year as Sir Walter Scott, 1771, just one hundred years before our visit, and, after studying for the Church, adopted medicine as his profession. He served a short time with a doctor at Selkirk, before completing his course at the University of Edinburgh, and sailed in 1792 for the East Indies in the service of the East India Company. Later he joined an association for the promotion of discovery in Africa, and in 1795 he explored the basin of the Niger. In 1798 he was in London, and in 1801 began practice as a doctor in Peebles. He told Sir Walter Scott, after passing through one of the severe winters in Peebleshire, that he would rather return to the wilds of Africa than pass another winter there. He returned to London in December 1803 to sail with another expedition, but its departure was delayed for a short time, so he again visited Peebles, and astonished the people there by bringing with him a black man named “Sidi Omback Boubi,” who was to be his tutor in Arabic. Meantime, in 1779, he had published a book entitled Travels in the Interior of Africa, which caused a profound sensation at the time on account of the wonderful stories it contained of adventures in what was then an unknown part of the world. This book of “Adventures of Mungo Park” was highly popular and extensively read throughout the country, by ourselves amongst the rest.

It was not until January 29th, 1805, that the expedition left Spithead, and before Mungo Park left Peebles he rode over to Clovenfords, where Sir Walter Scott was then residing, to stay a night with him at Ashestiel. On the following morning Sir Walter accompanied him a short distance on the return journey, and when they were parting where a small ditch divided the moor from the road Park’s horse stumbled a little. Sir Walter said, “I am afraid, Mungo, that is a bad omen,” to which Park replied, smiling, “Friets (omens) follow those that look for them,” and so they parted for ever. In company with his friends Anderson and Scott he explored the rivers Gambia and Niger, but his friends died, and Dr. Park himself was murdered by hostile natives who attacked his canoe in the River Niger.

Quite near our lodgings was the house where this famous African traveller lived and practised blood-letting as a surgeon, and where dreams of the tent in which he was once a prisoner and of dark faces came to him at night, while the door at which his horse was tethered as he went to see Sir Walter Scott, and the window out of which he put his head when knocked up in the night, were all shown as objects of interest to visitors. Mungo had at least one strange patient, and that was the Black Dwarf, David Ritchie, who lies buried close to the gate in the old churchyard. This was a horrid-looking creature, who paraded the country as a privileged beggar. He affected to be a judge of female beauty, and there was a hole in the wall of his cottage through which the fair maidens had to look, a rose being passed through if his fantastic fancies were pleased; but if not, the tiny window was closed in their faces. He was known to Sir Walter Scott, who adopted his name in one of his novels, The Bowed Davie of the Windus. His cottage, which was practically in the same state as at the period of David Ritchie’s death, bore a tablet showing that it had been restored by the great Edinburgh publishers W. and R. Chambers, who were natives of Peebles, and worded: “In memory D.R., died 1811. W. and R. Chambers, 1845.”

Dr. Pennicuick, who flourished A.D. 1652-1722, had written:

Peebles, the Metropolis of the shire,

Six times three praises doth from me require;

Three streets, three ports, three bridges, it adorn,

And three old steeples by three churches borne,

Three mills to serve the town in time of need.

On Peebles water, and on River Tweed,

Their arms are proper, and point forth their meaning,

Three salmon fishes nimbly counter swimming;

but there were other “Threes” connected with Peebles both before and after the doctor’s time: “The Three Tales of the Three Priests of Peebles,” supposed to have been told about the year 1460 before a blazing fire at the “Virgin Inn.”

There were also the Three Hopes buried in the churchyard, whose tombstone records:

Here lie three Hopes enclosed within,

Death’s prisoners by Adam’s sin;

Yet rest in hope that they shall be

Set by the Second Adam free.

And there were probably other triplets, but when my brother suggested there were also three letter e’s in the name of Peebles, I reminded him that it was closing-time, and also bed-time, so we rested that night in an old inn such as Charles Dickens would have been delighted to patronise.

(Distance walked twenty-five miles.)

Tuesday, October 10th.

This was the day of the Great Peebles Fair, and everybody was awake early, including ourselves. We left the “Cross Keys” hotel at six o’clock in the morning, and a very cold one it was, for there had been a sharp frost during the night. The famous old Cross formerly stood near our inn, and the Cross Church close at hand, or rather all that remained of them after the wars. In spite of the somewhat modern appearance of the town, which was probably the result of the business element introduced by the establishment of the woollen factories, Peebles was in reality one of the ancient royal burghs, and formerly an ecclesiastical centre of considerable importance, for in the reign of Alexander III several very old relics were said to have been found, including what was supposed to be a fragment of the true Cross, and with it the calcined bones of St. Nicholas, who suffered in the Roman persecution, A.D. 294. On the strength of these discoveries the king ordered a magnificent church to be erected, which caused Peebles to be a Mecca for pilgrims, who came there from all parts to venerate the relics. The building was known as the Cross Church, where a monastery was founded at the desire of James III in 1473 and attached to the church, in truly Christian spirit, one-third of its revenues being devoted to the redemption of Christian captives who remained in the hands of the Turks after the Crusades.

ST. ANDREWS CHURCH, PEEBLES, A.D. 1195.

If we had visited the town in past ages, there would not have been any fair on October 10th, since the Great Fair, called the Beltane Festival, was then held on May Day; but after the finding of the relics it was made the occasion on which to celebrate the “Finding of the Cross,” pilgrims and merchants coming from all parts to join the festivities and attend the special celebrations at the Cross Church. On the occasion of a Beltane Fair it was the custom to light a fire on the hill, round which the young people danced and feasted on cakes made of milk and eggs. We thought Beltane was the name of a Sun-god, but it appeared that it was a Gaelic word meaning Bel, or Beal’s-fire, and probably originated from the Baal mentioned in Holy Writ.

As our next great object of interest was Abbotsford, the last house inhabited by Sir Walter Scott, our course lay alongside the River Tweed. We were fortunate in seeing the stream at Peebles, which stood at the entrance to one of the most beautiful stretches in the whole of its length of 103 miles, 41 of which lay in Peeblesshire. The twenty miles along which we walked was magnificent river scenery.

We passed many castles and towers and other ancient fortifications along its banks, the first being at Horsburgh, where the castle looked down upon a grass field called the Chapelyards, on which formerly stood the chapel and hospice of the two saints, Leonard and Lawrence. At this hospice pilgrims from England were lodged when on their way to Peebles to attend the feasts of the “Finding of the Cross” and the “Exaltation of the Cross,” which were celebrated at Beltane and Roodmass respectively, in the ancient church and monastery of the Holy Cross. It was said that King James I of England on his visits to Peebles was also lodged here, and it is almost certain the Beltane Sports suggested to him his famous poem, “Peebles to the Play,” one of its lines being:

Hope Kailzie, and Cardrona, gathered out thickfold,

Singing “Hey ho, rumbelow, the young folks were full bold.”

both of which places could be seen from Horsburgh Castle looking across the river.

We saw the Tower of Cardrona, just before entering the considerable village, or town, of Innerleithen at six miles from Peebles, and although the time was so early, we met many people on their way to the fair. Just before reaching Innerleithen we came to a sharp deep bend in the river, which we were informed was known as the “Dirt Pot” owing to its black appearance. At the bottom of this dark depth the silver bells of Peebles were supposed to be lying. We also saw Glennormiston House, the residence of William Chambers, who, with his brother, Robert, founded Chambers’s Journal of wide-world fame, and authors, singly and conjointly, of many other volumes. The two brothers were both benefactors to their native town of Peebles, and William became Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and the restorer of its ancient Cathedral of St. Giles’s. His brother Robert died earlier in that very year in which we were walking. We reached Innerleithen just as the factory operatives were returning from breakfast to their work at the woollen factories, and they seemed quite a respectable class of people. Here we called at the principal inn for our own breakfast, for which we were quite ready, but we did not know then that Rabbie Burns had been to Innerleithen, where, as he wrote, he had from a jug “a dribble o’ drink,” or we should have done ourselves the honour of calling at the same place. At Innerleithen we came to another “Bell-tree Field,” where the bell hung on the branch of a tree to summon worshippers to church, and there were also some mineral springs which became famous after the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s novel, St. Ronan’s Well.

Soon after leaving Innerleithen we could see Traquair House towering above the trees by which it was surrounded. Traquair was said to be the oldest inhabited house in Scotland. Sir Walter Scott knew it well, it being quite near to Ashiestiel, where he wrote “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” “Marmion,” and “The Lady of the Lake.” It was one of the prototypes of “Tully Veolan” in his Waverley. There was no abode in Scotland more quaint and curious than Traquair House, for it was turreted, walled, buttressed, windowed, and loopholed, all as in the days of old. Within were preserved many relics of the storied past and also of royalty. Here was the bed on which Queen Mary slept in 1566; here also the oaken cradle of the infant King James VI. The library was rich in valuable and rare books and MSS. and service books of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries in beautiful penmanship upon fine vellum. The magnificent avenue was grass-grown, the gates had not been opened for many years, while the pillars of the gateway were adorned with two huge bears standing erect and bearing the motto: “Judge Nocht.” Magnificent woods adorned the grounds, remains of the once-famous forest of Ettrick, said to be the old classical forest of Caledon of the days of King Arthur.

Here was also Flora Hill, with its beautiful woods, where Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, lays the scene of his exquisite poem “Kilmeny” in the Queen’s Wake, where—

Bonnie Kilmeny gae’d up the Glen,

But it wisna to meet Duneira’s men, etc.

Through beautiful scenery we continued alongside the Tweed, and noticed that even the rooks could not do without breakfast, for they were busy in a potato field. We were amused to see them fly away on our approach, some of them with potatoes in their mouths, and, like other thieves, looking quite guilty.

Presently we came to a solitary fisherman standing knee-deep in the river, with whom we had a short conversation. He said he was fishing for salmon, which ascended the river from Berwick about that time of the year and returned in May. We were rather amused at his mentioning the return journey, as from the frantic efforts he was making to catch the fish he was doing his best to prevent them from coming back again. He told us he had been fishing there since daylight that morning, and had caught nothing. By way of sympathy my brother told him a story of two young men who walked sixteen miles over the hills to fish in a stream. They stayed that night at the nearest inn, and started out very early the next morning. When they got back to the hotel at night they wrote the following verse in the visitors’ book:

Hickory dickory dock!

We began at six o’clock,

We fished till night without a bite.

Hickory dickory dock!

This was a description, he said, of real fishermen’s luck, but whether the absence of the “bite” referred to the fishermen or to the fish was not quite clear. It had been known to apply to both.

Proceeding further we met a gentleman walking along the road, of whom we made inquiries about the country we were passing through. He told us that the castle we could see across the river was named “Muckle Mouthed Meg.” A certain man in ancient times, having offended against the laws, was given a choice for a sentence by the King of Scotland—-either he must marry Muckle Mouthed Meg, a woman with a very large mouth, or suffer death. He chose the first, and the pair lived together in the old castle for some years. We told him we were walking from John o’ Groat’s to Land’s End, but when he said he had passed John o’ Groat’s in the train, we had considerable doubts as to the accuracy of his statements, for there was no railway at all in the County of Caithness in which John o’ Groat’s was situated. We therefore made further inquiries about the old castle, and were informed that the proper name of it was Elibank Castle, and that it once belonged to Sir Gideon Murray, who one night caught young Willie Scott of Oakwood Tower trying to “lift the kye.” The lowing of the cattle roused him up, and with his retainers he drove off the marauders, while his lady watched the fight from the battlement of the Tower. Willie, or, to be more correct, Sir William Scott, Junr., was caught and put in the dungeon. Sir Gideon Murray decided to hang him, but his lady interposed: “Would ye hang the winsome Laird o’ Harden,” she said, “when ye hae three ill-favoured daughters to marry?” Sir Willie was one of the handsomest men of his time, and when the men brought the rope to hang him he was given the option of marrying Muckle Mou’d Meg or of being hanged with a “hempen halter.” It was said that when he first saw Meg he said he preferred to be hanged, but he found she improved on closer acquaintance, and so in three days’ time a clergyman said, “Wilt thou take this woman here present to be thy lawful wife?” knowing full well what the answer must be. Short of other materials, the marriage contract was written with a goose quill on the parchment head of a drum. Sir William found that Meg made him a very good wife in spite of her wide mouth, and they lived happily together, the moral being, we supposed, that it is not always the prettiest girl that makes the best wife.

Shortly afterwards we left the River Tweed for a time while we walked across the hills to Galashiels, and on our way to that town we came to a railway station near which were some large vineries. A carriage was standing at the entrance to the gardens, where two gentlemen were buying some fine bunches of grapes which we could easily have disposed of, for we were getting rather hungry, but as they did not give us the chance, we walked on. Galashiels was formerly only a village, the “shiels” meaning shelters for sheep, but it had risen to importance owing to its woollen factories. It was now a burgh, boasting a coat-of-arms on which was represented a plum-tree with a fox on either side, and the motto, “Sour plums of Galashiels.” The origin of this was an incident that occurred in 1337, in the time of Edward III, when some Englishmen who were retreating stopped here to eat some wild plums. While they were so engaged they were attacked by a party of Scots with swords, who killed every one of them, throwing their bodies into a trench afterwards known as the “Englishman’s Syke.” We passed a road leading off to the left to Stow, where King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table were said to have defeated the Heathens. We left Galashiels by the Melrose Road, and, after walking about a mile and a half, we turned aside to cross the River Tweed, not by a ferry, as that was against our rule, but by a railway bridge. No doubt this was against the railway company’s by-laws and regulations, but it served our purpose, and we soon reached Abbotsford, that fine mansion, once the residence of the great Sir Walter Scott, the king of novelists, on the building of which he had spent a great amount of money, and the place of his death September 21st, 1832.

Abbotsford, including the gardens, park, walks and woods, was all his own creation, and was so named by him because the River Tweed was crossed at that point by the monks on their way to and from Melrose Abbey in the olden times.

We found the house in splendid condition and the garden just as Sir Walter had left it. We were shown through the hall, study, library, and drawing-room, and even his last suit of clothes, with his white beaver hat, was carefully preserved under a glass case. We saw much armour, the largest suit belonging formerly to Sir John Cheney, the biggest man who fought at the battle of Bosworth Field. The collection of arms gathered out of all ages and countries was said to be the finest in the world, including Rob Roy Macgregor’s gun, sword, and dirk, the Marquis of Montrose’s sword, and the rifle of Andreas Hofer the Tyrolese patriot.

Amongst these great curios was the small pocket-knife used by Sir Walter when he was a boy. We were shown the presents given to him from all parts of the kingdom, and from abroad, including an ebony suite of furniture presented to him by King George IV. There were many portraits and busts of himself, and his wife and children, including a marble bust of himself by Chantrey, the great sculptor, carved in the year 1820. The other portraits included one of Queen Elizabeth, another of Rob Roy; a painting of Queen Mary’s head, after it had been cut off at Fotheringay, and a print of Stothard’s Canterbury Pilgrims. We also saw an iron box in which Queen Mary kept her money for the poor, and near this was her crucifix. In fact, the place reminded us of some great museum, for there were numberless relics of antiquity stored in every nook and corner, and in the most unlikely places. We were sorry we had not time to stay and take a longer survey, for the mansion and its surroundings form one of the great sights of Scotland, whose people revere the memory of the great man who lived there.

The declining days of Sir Walter were not without sickness and sorrow, for he had spent all the money obtained by the sale of his books on this palatial mansion. After a long illness, and as a last resource, he was taken to Italy; but while there he had another apoplectic attack, and was brought home again, only just in time to die. He expressed a wish that Lockhart, his son-in-law, should read to him, and when asked from what book, he answered, “Need you ask? There is but one.” He chose the fourteenth chapter of St. John’s Gospel, and when it was ended, he said, “Well, this is a great comfort: I have followed you distinctly, and I feel as if I were yet to be myself again.” In an interval of consciousness he said, “Lockhart! I may have but a minute to speak to you, my dear; be a good man, be virtuous, be religious, be a good man. Nothing else will give you any comfort when you come to lie here.”

A friend who was present at the death of Sir Walter wrote: “It was a beautiful day—so warm that every window was wide open, and so perfectly still that the sound of all others most delicious to his ear, the gentle ripple of the Tweed over its pebbles, was distinctly audible—as we kneeled around his bed, and his eldest son kissed and closed his eyes.” We could imagine the wish that would echo in more than one mind as Sir Walter’s soul departed, perhaps through one of the open windows, “Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his.”

So coldly sweet, so deadly fair,

We start, for soul is wanting there;

It is the loneliness in death

That parts not quite with parting breath,

But beauty with that fearful bloom,

The hue which haunts it to the tomb,

Expression’s last receding ray;

A gilded halo hov’ring round decay.

We passed slowly through the garden and grounds, and when we reached the road along which Sir Walter Scott had so often walked, we hurried on to see the old abbey of Melrose, which was founded by King David I. On our way we passed a large hydropathic establishment and an asylum not quite completed, and on reaching Melrose we called at one of the inns for tea, where we read a description by Sir Walter of his “flitting” from Ashiestiel, his former residence, to his grand house at Abbotsford. The flitting took place at Whitsuntide in 1812, so, as he died in 1832, he must have lived at Abbotsford about twenty years. He was a great collector of curios, and wrote a letter describing the comical scene which took place on that occasion. “The neighbours,” he wrote, “have been very much delighted with the procession of furniture, in which old swords, bows, targets, and lances made a very conspicuous show. A family of turkeys was accommodated within the helmet of some preux chevalier of ancient Border fame, and the very cows, for aught I know, were bearing banners and muskets. I assure you that this caravan, attended by a dozen ragged, rosy, peasant children carrying fishing-rods and spears, and leading ponies, greyhounds, and spaniels, would, as it crossed the Tweed, have furnished no bad subject for the pencil.”

Melrose Abbey was said to afford the finest specimen of Gothic architecture and Gothic sculpture of which Scotland could boast, and the stone of which it had been built, though it had resisted the weather for many ages, retained perfect sharpness, so that even the most minute ornaments seemed as entire as when they had been newly wrought. In some of the cloisters there were representations of flowers, leaves, and vegetables carved in stone with “accuracy and precision so delicate that it almost made visitors distrust their senses when they considered the difficulty of subjecting so hard a substance to such intricate and exquisite modulation.” This superb convent was dedicated to St. Mary, and the monks were of the Cistercian Order, of whom the poet wrote:

Oh, the monks of Melrose made gude kail (broth)

On Fridays when they fasted;

Nor wanted they gude beef and ale,

So lang’s their neighbours’ lasted.

There were one hundred monks at Melrose in the year 1542, and it was supposed that in earlier times much of the carving had been done by monks under strong religious influences. The rose predominated amongst the carved flowers, as it was the abbot’s favourite flower, emblematic of the locality from which the abbey took its name. The curly green, or kale, which grew in nearly every garden in Scotland, was a very difficult plant to sculpture, but was so delicately executed here as to resemble exactly the natural leaf; and there was a curious gargoyle representing a pig playing on the bagpipes, so this instrument must have been of far more ancient origin than we had supposed when we noticed its absence from the instruments recorded as having been played when Mary Queen of Scots was serenaded in Edinburgh on her arrival in Scotland.

Under the high altar were buried the remains of Alexander II, the dust of Douglas the hero of Otterburn, and others of his illustrious and heroic race, as well as the remains of Sir Michael Scott. Here too was buried the heart of King Robert the Bruce. It appeared that Bruce told his son that he wished to have his heart buried at Melrose; but when he was ready to die and his friends were assembled round his bedside, he confessed to them that in his passion he had killed Comyn with his own hand, before the altar, and had intended, had he lived, to make war on the Saracens, who held the Holy Land, for the evil deeds he had done. He requested his dearest friend, Lord James Douglas, to carry his heart to Jerusalem and bury it there. Douglas wept bitterly, but as soon as the king was dead he had his heart taken from his body, embalmed, and enclosed in a silver case which he had made for it, and wore it suspended from his neck by a string of silk and gold. With some of the bravest men in Scotland he set out for Jerusalem, but, landing in Spain, they were persuaded to take part in a battle there against the Saracens. Douglas, seeing one of his friends being hard pressed by the enemy, went to his assistance and became surrounded by the Moors himself. Seeing no chance of escape, he took from his neck the heart of Bruce, and speaking to it as he would have done to Bruce if alive, said, “Pass first in the fight as thou wert wont to do, and Douglas will follow thee or die.” With these words he threw the king’s heart among the enemy, and rushing forward to the place where it fell, was there slain, and his body was found lying on the silver case. Most of the Scots were slain in this battle with the Moors, and they that remained alive returned to Scotland, the charge of Bruce’s heart being entrusted to Sir Simon Lockhard of Lee, who afterwards for his device bore on his shield a man’s heart with a padlock upon it, in memory of Bruce’s heart which was padlocked in the silver case. For this reason, also, Sir Simon’s name was changed from Lockhard to Lockheart, and Bruce’s heart was buried in accordance with his original desire at Melrose.

Sir Michael Scott of Balwearie, who also lies buried in the abbey, flourished in the thirteenth century. His great learning, chiefly acquired in foreign countries, together with an identity in name, had given rise to a certain confusion, among the earlier historians, between him and Michael Scott the “wondrous wizard and magician” referred to by Dante in Canto xxmo of the “Inferno.” Michael Scott studied such abstruse subjects as judicial astrology, alchemy, physiognomy, and chiromancy, and his commentary on Aristotle was considered to be of such a high order that it was printed in Venice in 1496. Sir Walter Scott referred to Michael Scott:

The wondrous Michael Scott

A wizard, of such dreaded fame,

That when in Salamanca’s Cave

Him listed his magic wand to wave

The bells would ring in Notre Dame,

and he explained the origin of this by relating the story that Michael on one occasion when in Spain was sent as an Ambassador to the King of France to obtain some concessions, but instead of going in great state, as usual on those occasions, he evoked the services of a demon in the shape of a huge black horse, forcing it to fly through the air to Paris. The king was rather offended at his coming in such an unceremonious manner, and was about to give him a contemptuous refusal when Scott asked him to defer his decision until his horse had stamped its foot three times. The first stamp shook every church in Paris, causing all the bells to ring; the second threw down three of the towers of the palace; and when the infernal steed had lifted up his hoof for the third time, the king stopped him by promising Michael the most ample concessions.

A modern writer, commenting upon this story, says, “There is something uncanny about the Celts which makes them love a Trinity of ideas, and the old stories of the Welsh collected in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries include a story very similar about Kilhwch, cousin to Arthur, who threatens if he cannot have what he wants that he will set up three shouts than which none were ever heard more deadly and which will be heard from Pengwaed in Cornwall to Dinsol in the North and Ergair Oerful in Ireland. The Triads show the method best and furnish many examples, quoting the following:

Three things are best when hung—salt fish, a wet hat, and an Englishman.

Three things are difficult to get—gold from the miser, love from the devil, and courtesy from the Englishman.

The three hardest things—a granite block, a miser’s barley loaf, and an Englishman’s heart.

But perhaps the best known is one translated long ago from the Welsh:

A woman, a dog, and a walnut tree,

The more they are beaten, the better they be.

But to return to Michael Scott. Another strange story about Michael was his adventure with the witch of Falschope. To avenge himself upon her for striking him suddenly with his own wand whereby he was transformed for a time and assumed the appearance of a hare, Michael sent his man with two greyhounds to the house where the witch lived, to ask the old lady to give him a bit of bread for the greyhounds; if she refused he was to place a piece of paper, which he handed to him, over the top of the house door. The witch gave the man a curt refusal, and so he fastened the paper, on which were some words, including, “Michael Scott’s man sought meat and gat nane,” as directed. This acted as a spell, and the old witch, who was making cakes for the reapers then at work in the corn, now began to dance round the fire (which, as usual in those days, was burning in the middle of the room) and to sing the words:

“Maister Michael Scott’s man

Sought meat and gat nane.”

and she had to continue thus until the spell was broken. Meantime, her husband and the reapers who were with him were wondering why the cakes had not reached them, so the old man sent one of the reapers to inquire the reason. As soon as he went through the door he was caught by the spell and so had to perform the same antics as his mistress. As he did not return, the husband sent man after man until he was alone, and then went himself. But, knowing all about the quarrel between Michael and his wife, and having seen the wizard on the hill, he was rather more cautious than his men, so, instead of going through the door, he looked through the window. There he saw the reapers dragging his wife, who had become quite exhausted, sometimes round, and sometimes through the fire, singing the chorus as they did so. He at once saddled his horse and rode as fast as he could to find Michael, who good-naturedly granted his request, and directed him to enter his house backwards, removing the paper from above the door with his left hand as he went in. The old man lost no time in returning home, where he found them all still dancing furiously and singing the same rhyme; but immediately he entered, the supernatural performance ended, very much, we imagine, to the relief of all concerned.

Michael Scott was at one time, it was said, much embarrassed by a spirit for whom he had to find constant employment, and amongst other work he commanded him to build a dam or other weir across the River Tweed at Kelso. He completed that in a single night. Michael next ordered him to divide the summit of the Eildon Hill in three parts; but as this stupendous work was also completed in one night, he was at his wits’ end what work to find him to do next. At last he bethought himself of a job that would find him constant employment. He sent him to the seashore and employed him at the hopeless and endless task of making ropes of sand there, which as fast as he made them were washed away by the tides. The three peaks of Eildon Hill, of nearly equal height, are still to be seen. Magnificent views are to be obtained from their tops, which Sir Walter Scott often frequented and of which he wrote, “I can stand on the Eildon and point out forty-three places famous in war and in verse.”

Another legend connected with these hills was that in the “Eildon caverns vast” a cave existed where the British King Arthur and his famous Knights of the Round Table lie asleep waiting the blast of the bugle which will recall them from Fairyland to lead the British on to a victory that will ensure a united and glorious Empire. King Arthur has a number of burial-places of the same character, according to local stories both in England and Wales, and even one in Cheshire at Alderley Edge, close By the “Wizard Inn,” which title refers to the story.

Melrose and district has been hallowed by the influence and memory of Sir Walter Scott, who was to Melrose what Shakespeare was to Stratford-on-Avon, and he has invested the old abbey with an additional halo of interest by his “Lay of the Last Minstrel,” a copy of which we saw for the first time at the inn where we called for tea. We were greatly interested, as it related to the neighbourhood we were about to pass through in particular, and we were quite captivated with its opening lines, which appealed so strongly to wayfarers like ourselves:

The way was long, the wind was cold.

The Minstrel was infirm and old;

His wither’d cheek, and tresses gray,

Seem’d to have known a better day;

The harp, his sole remaining joy,

Was carried by an orphan boy.

The last of all the Bards was he,

Who sung of Border chivalry.

We were now nearing the Borders of Scotland and England, where this Border warfare formerly raged for centuries. The desperadoes engaged in it on the Scottish side were known as Moss-troopers, any of whom when caught by the English were taken to Carlisle and hanged near there at a place called Hairibee. Those who claimed the “benefit of clergy” were allowed to repeat in Latin the “Miserere mei,” at the beginning of the 51st Psalm, before they were executed, this becoming known as the “neck-verse.”

William of Deloraine was one of the most desperate Moss-troopers ever engaged in Border warfare, but he, according to Sir Walter Scott:

By wily turns, by desperate bounds,

Had baffled Percy’s best blood-hounds;

In Eske or Liddel, fords were none,

But he would ride them, one by one;

Steady of heart, and stout of hand.

As ever drove prey from Cumberland;

Five times outlawed had he been,

By England’s King, and Scotland’s Queen.

When Sir Michael Scott was buried in Melrose Abbey his Mystic Book—which no one was ever to see except the Chief of Branxholm, and then only in the time of need—was buried with him. Branxholm Tower was about eighteen miles from Melrose and situated in the vale of Cheviot. After the death of Lord Walter (who had been killed in the Border warfare), a gathering of the kinsmen of the great Buccleuch was held there, and the “Ladye Margaret” left the company, retiring laden with sorrow and her impending troubles to her bower. It was a fine moonlight night when—

From amid the arméd train

She called to her, William of Deloraine.

and sent him for the mighty book to Melrose Abbey which was to relieve her of all her troubles.

“Sir William of Deloraine, good at need,

Mount thee on the wightest steed;

Spare not to spur, nor stint to ride.

Until thou come to fair Tweedside;

And in Melrose’s holy pile

Seek thou the Monk of St. Mary’s aisle.

Greet the Father well from me;

Say that the fated hour is come,

And to-night he shall watch with thee,

To win the treasure of the tomb:

For this will be St. Michael’s night,

And, though stars be dim, the moon is bright;

And the Cross, of bloody red,

Will point to the grave of the mighty dead.

“What he gives thee, see thou keep;

Stay not thou for food or sleep:

Be it scroll, or be it book,

Into it, Knight, thou must not look;

If thou readest, thou art lorn!

Better had’st thou ne’er been born.”—

“O swiftly can speed my dapple-grey steed,

Which drinks of the Teviot clear;

Ere break of day,” the Warrior ‘gan say,

“Again will I be here:

And safer by none may thy errand be done,

Than, noble dame, by me;

Letter nor line know I never a one,

Wer’t my neck-verse at Hairibee.”

Deloraine lost no time in carrying out his Ladye’s wishes, and rode furiously on his horse to Melrose Abbey in order to be there by midnight, and as described in Sir Walter Scott’s “Lay of the Last Minstrel”:

Short halt did Deloraine make there;

Little reck’d he of the scene so fair

With dagger’s hilt, on the wicket strong,

He struck full loud, and struck full long.

The porter hurried to the gate—

“Who knocks so loud, and knocks so late?”

“From Branksome I,” the warrior cried;

And straight the wicket open’d wide

For Branksome’s Chiefs had in battle stood,

To fence the rights of fair Melrose;

And lands and livings, many a rood,

Had gifted the Shrine for their souls’ repose.

Bold Deloraine his errand said;

The porter bent his humble head;

With torch in hand, and feet unshod.

And noiseless step, the path he trod.

The archèd cloister, far and wide,

Rang to the warrior’s clanking stride,

Till, stooping low his lofty crest,

He enter’d the cell of the ancient priest,

And lifted his barred aventayle,

To hail the Monk of St. Mary’s aisle.

“The Ladye of Branksome greets thee by me,

Says, that the fated hour is come,

And that to-night I shall watch with thee,

To win the treasure of the tomb.”

From sackcloth couch the Monk arose,

With toil his stiffen’d limbs he rear’d;

A hundred years had flung their snows

On his thin locks and floating beard.

And strangely on the Knight look’d he,

And his blue eyes gleam’d wild and wide;

“And, darest thou, Warrior! seek to see

What heaven and hell alike would hide?

My breast, in belt of iron pent,

With shirt of hair and scourge of thorn;

For threescore years, in penance spent.

My knees those flinty stones have worn;

Yet all too little to atone

For knowing what should ne’er be known.

Would’st thou thy every future year

In ceaseless prayer and penance drie,

Yet wait thy latter end with fear

Then, daring Warrior, follow me!”

“Penance, father, will I none;

Prayer know I hardly one;

For mass or prayer can I rarely tarry,

Save to patter an Ave Mary,

When I ride on a Border foray.

Other prayer can I none;

So speed me my errand, and let me be gone.”

Again on the Knight look’d the Churchman old,

And again he sighed heavily;

For he had himself been a warrior bold.

And fought in Spain and Italy.

And he thought on the days that were long since by,

When his limbs were strong, and his courage was high—

Now, slow and faint, he led the way,

Where, cloister’d round, the garden lay;

The pillar’d arches were over their head,

And beneath their feet were the bones of the dead.

The moon on the east oriel shone

Through slender shafts of shapely stone,

The silver light, so pale and faint,

Shew’d many a prophet, and many a saint,

Whose image on the glass was dyed;

Full in the midst, his Cross of Red

Triumphal Michael brandished,

And trampled the Apostate’s pride.

The moon beam kiss’d the holy pane,

And threw on the pavement a bloody stain.

They sate them down on a marble stone,—

(A Scottish monarch slept below;)

Thus spoke the Monk, in solemn tone—

“I was not always a man of woe;

For Paynim countries I have trod,

And fought beneath the Cross of God:

Now, strange to my eyes thine arms appear.

And their iron clang sounds strange to my ear.

“In these far climes it was my lot

To meet the wondrous Michael Scott;

Some of his skill he taught to me;

And, Warrior, I could say to thee

The words that cleft Eildon hills in three,

And bridled the Tweed with a curb of stone:

But to speak them were a deadly sin;

And for having but thought them my heart within,

A treble penance must be done.

“When Michael lay on his dying bed,

His conscience was awakened

He bethought him of his sinful deed,

And he gave me a sign to come with speed.

I was in Spain when the morning rose,

But I stood by his bed ere evening close.

The words may not again be said

That he spoke to me, on death-bed laid;

They would rend this Abbaye’s massy nave,

And pile it in heaps above his grave.

“I swore to bury his Mighty Book,

That never mortal might therein look;

And never to tell where it was hid,

Save at his Chief of Branksome’s need:

And when that need was past and o’er,

Again the volume to restore.

I buried him on St. Michael’s night,

When the bell toll’d one, and the moon was bright,

And I dug his chamber among the dead,

When the floor of the chancel was stained red,

That his patron’s cross might over him wave,

And scare the fiends from the Wizard’s grave.

“It was a night of woe and dread,

When Michael in the tomb I laid!

Strange sounds along the chancel pass’d,

The banners waved without a blast”—

Still spoke the Monk, when the bell toll’d one!—

I tell you, that a braver man

Than William of Deloraine, good at need,

Against a foe ne’er spurr’d a steed;

Yet somewhat was he chill’d with dread,

And his hair did bristle upon his head.

“Lo, Warrior! now, the Cross of Red

Points to the grave of the mighty dead;

Within it burns a wondrous light,

To chase the spirits that love the night:

That lamp shall burn unquenchably,

Until the eternal doom shall be.”—

Slow moved the Monk to the broad flag-stone,

Which the bloody Cross was traced upon:

He pointed to a secret nook;

An iron bar the Warrior took;

And the Monk made a sign with his wither’d hand,

The grave’s huge portal to expand.

With beating heart to the task he went;

His sinewy frame o’er the grave-stone bent;

With bar of iron heaved amain,

Till the toil-drops fell from his brows, like rain.

It was by dint of passing strength,

That he moved the massy stone at length.

I would you had been there, to see

How the light broke forth so gloriously,

Stream’d upward to the chancel roof,

And through the galleries far aloof!

No earthly flame blazed e’er so bright:

It shone like heaven’s own blessed light,

And, issuing from the tomb,

Show’d the Monk’s cowl, and visage pale,

Danced on the dark-brow’d Warrior’s mail,

And kiss’d his waving plume.

Before their eyes the Wizard lay,

As if he had not been dead a day.

His hoary beard in silver roll’d.

He seem’d some seventy winters old;

A palmer’s amice wrapp’d him round,

With a wrought Spanish baldric bound,

Like a pilgrim from beyond the sea:

His left hand held his Book of Might;

A silver cross was in his right;

The lamp was placed beside his knee:

High and majestic was his look,

At which the fellest fiends had shook.

And all unruffled was his face:

They trusted his soul had gotten grace.

Often had William of Deloraine

Rode through the battle’s bloody plain,

And trampled down the warriors slain,

And neither known remorse nor awe;

Yet now remorse and awe he own’d;

His breath came thick, his head swam round.

When this strange scene of death he saw.

Bewilder’d and unnerved he stood.

And the priest pray’d fervently and loud:

With eyes averted prayed he;

He might not endure the sight to see.

Of the man he had loved so brotherly.

And when the priest his death-prayer had pray’d,

Thus unto Deloraine he said:—

“Now, speed thee what thou hast to do,

Or, Warrior, we may dearly rue;

For those, thou may’st not look upon,

Are gathering fast round the yawning stone!”—

Then Deloraine, in terror, took

From the cold hand the Mighty Book,

With iron clasp’d, and with iron bound:

He thought, as he took it, the dead man frown’d;

But the glare of the sepulchral light,

Perchance, had dazzled the Warrior’s sight.

When the huge stone sunk o’er the tomb.

The night return’d in double gloom;

For the moon had gone down, and the stars were few;

And, as the Knight and Priest withdrew.

With wavering steps and dizzy brain,

They hardly might the postern gain.

‘Tis said, as through the aisles they pass’d,

They heard strange noises on the blast;

And through the cloister-galleries small,

Which at mid-height thread the chancel wall,

Loud sobs, and laughter louder, ran,

And voices unlike the voices of man;

As if the fiends kept holiday,

Because these spells were brought to day.

I cannot tell how the truth may be;

I say the tale as ’twas said to me.

“Now, hie thee hence,” the Father said,

“And when we are on death-bed laid,

O may our dear Ladye, and sweet St. John,

Forgive our souls for the deed we have done!”—

The Monk return’d him to his cell,

And many a prayer and penance sped;

When the convent met at the noontide bell—

The Monk of St. Mary’s aisle was dead!

Before the cross was the body laid,

With hands clasp’d fast, as if still he pray’d.

What became of Sir William Deloraine and the wonderful book on his return journey we had no time to read that evening, but we afterwards learned he fell into the hands of the terrible Black Dwarf. We had decided to walk to Hawick if possible, although we were rather reluctant to leave Melrose. We had had one good tea on entering the town, and my brother suggested having another before leaving it, so after visiting the graveyard of the abbey, where the following curious epitaph appeared on one of the stones, we returned to the inn, where the people were highly amused at seeing us return so soon and for such a purpose:

The earth goeth to the earth

Glist’ring like gold;

The earth goeth to the earth

Sooner than it wold;

The earth builds on the earth

Castles and Towers;

The earth says to the earth,

All shall be ours.

Still, we were quite ready for our second tea, and wondered whether there was any exercise that gave people a better appetite and a greater joy in appeasing it than walking, especially in the clear and sharp air of Scotland, for we were nearly always extremely hungry after an hour or two’s walk. When the tea was served, I noticed that my brother lingered over it longer than usual, and when I reminded him that the night would soon be on us, he said he did not want to leave before dark, as he wanted to see how the old abbey appeared at night, quoting Sir Walter Scott as the reason why:

If thou would’st view fair Melrose aright,

Go visit it by the pale moonlight;

For the gay beams of lightsome day

Gild, but to flout, the ruins grey.

When the broken arches are black in night,

And each shafted oriel glimmers white;

When the cold light’s uncertain shower

Streams on the ruin’d central tower;

When buttress and buttress, alternately,

Seem framed of ebon and ivory;

When silver edges the imagery.

And the scrolls that teach thee to live and die;

When distant Tweed is heard to rave,

And the owlet to hoot o’er the dead man’s grave,

Then go—but go alone the while—

Then view St. David’s ruin’d pile;

And, home returning, soothly swear.

Was ever scene so sad and fair?

I reminded my brother that there would be no moon visible that night, and that it would therefore be impossible to see the old abbey “by the pale moonlight”; but he said the starlight would do just as well for him, so we had to wait until one or two stars made their appearance, and then departed, calling at a shop to make a few small purchases as we passed on our way. The path alongside the abbey was entirely deserted. Though so near the town there was scarcely a sound to be heard, not even “the owlet to hoot o’er the dead man’s grave.” Although we had no moonlight, the stars were shining brightly through the ruined arches which had once been filled with stained glass, representing the figures “of many a prophet and many a saint.” It was a beautiful sight that remained in our memories long after other scenes had been forgotten.

According to the Koran there were four archangels: Azrael, the angel of death; Azrafil, who was to sound the trumpet at the resurrection; Gabriel, the angel of revelations, who wrote down the divine decrees; and Michael, the champion, who fought the battles of faith,—and it was this Michael whose figure Sir Walter Scott described as appearing full in the midst of the east oriel window “with his Cross of bloody red,” which in the light of the moon shone on the floor of the abbey and “pointed to the grave of the mighty dead” into which the Monk and William of Deloraine had to descend to secure possession of the “Mighty Book.”

After passing the old abbey and the shade of the walls and trees to find our way to the narrow and rough road along which we had to travel towards Hawick, we halted for a few moments at the side of the road to arrange the contents of our bags, in order to make room for the small purchases we had made in the town. We had almost completed the readjustment when we heard the heavy footsteps of a man approaching, who passed us walking along the road we were about to follow. My brother asked him if he was going far that way, to which he replied, “A goodish bit,” so we said we should be glad of his company; but he walked on without speaking to us further. We pushed the remaining things in our bags as quickly as possible, and hurried on after him. As we did not overtake him, we stood still and listened attentively, though fruitlessly, for not a footstep could we hear. We then accelerated our pace to what was known as the “Irishman’s Trig”—a peculiar step, quicker than a walk, but slower than a run—and after going some distance we stopped again to listen; but the only sound we could hear was the barking of a solitary dog a long distance away. This was very provoking, as we wanted to get some information about our road, which, besides being rough, was both hilly and very lonely, and more in the nature of a track than a road. Where the man could have disappeared to was a mystery on a road apparently without any offshoots, so we concluded he must have thought we contemplated doing him some bodily harm, and had either “bolted” or “clapp’d,” as my brother described it, behind some rock or bush, in which case he must have felt relieved and perhaps amused when he heard us “trigging” past him on the road.

LILLIESLEAF AND THE EILDON HILLS.

We continued along the lonely road without his company, with the ghostly Eildon Hills on one side and the moors on the other, until after walking steadily onwards for a few miles, we heard the roar of a mountain stream in the distance. When we reached it we were horrified to find it running right across our road. It looked awful in the dark, as it was quite deep, and although we could just see where our road emerged from the stream on the other side, it was quite impossible for us to cross in the dark. We could see a few lights some distance beyond the stream, but it was useless to attempt to call for help, since our voices could not be heard above the noise of the torrent. Our position seemed almost hopeless, until my brother said he thought he had seen a shed or a small house behind a gate some distance before coming to the stream. We resolved to turn back, and luckily we discovered it to be a small lodge guarding the entrance to a private road. We knocked at the door of the house, which was in darkness, the people having evidently gone to bed. Presently a woman asked what was wanted, and when we told her we could not get across the stream, she said there was a footbridge near by, which we had not seen in the dark, and told us how to find it a little higher up the stream. Needless to relate, we were very pleased when we got across the bridge, and we measured the distance across that turbulent stream in fifteen long strides.

We soon reached the lights we had seen, and found a small village, where at the inn we got some strange lodgings, and slept that night in a bed of a most curious construction, as it was in a dark place under the stairs, entered by a door from the parlour. But it was clean and comfortable, and we were delighted to make use of it after our long walk.

(Distance walked thirty miles.)

Wednesday, October 11th.

We had been warned when we retired to rest that it was most likely we should be wakened early in the morning by people coming down the stairs, and advised to take no notice of them, as no one would interfere with us or our belongings. We were not surprised, therefore, when we were aroused early by heavy footsteps immediately over our heads, which we supposed were those of the landlord as he came down the stairs. We had slept soundly, and, since there was little chance of any further slumber, we decided to get up and look round, the village before breakfast. We had to use the parlour as a dressing-room, and not knowing who might be coming down the stairs next, we dressed ourselves as quickly as possible. We found that the village was called Lilliesleaf, which we thought a pretty name, though we were informed it had been spelt in twenty-seven different ways, while the stream we came to in the night was known by the incongruous name of Ale Water. The lodge we had gone back to for information as to the means of crossing was the East Gate guarding one of the entrances to Riddell, a very ancient place where Sir Walter Scott had recorded the unearthing of two graves of special interest, one containing an earthen pot filled with ashes and arms, and bearing the legible date of 729, and the other dated 936, filled with the bones of a man of gigantic size.

A local historian wrote of the Ale Water that “it is one thing to see it on a summer day when it can be crossed by the stepping-stones, and another when heavy rains have fallen in the autumn—then it is a strong, deep current and carries branches and even trees on its surface, the ford at Riddell East Gate being impassable, and it is only then that we can appreciate the scene.” It seemed a strange coincidence that we should be travelling on the same track but in the opposite direction as that pursued by William Deloraine, and that we should have crossed the Ale Water about a fortnight later in the year, as Sir Walter described him in his “Lay” as riding along the wooded path when “green hazels o’er his basnet nod,” which indicated the month of September.

Unchallenged, thence pass’d Deloraine,

To ancient Riddell’s fair domain,

Where Aill, from mountain freed,

Down from the lakes did raving come;

Each wave was crested with tawny foam,

Like the mane of a chestnut steed.

In vain! no torrent, deep or broad.

Might bar the bold moss-trooper’s road.

At the first plunge the horse sunk low,

And the water broke o’er the saddlebow;

Above the foaming tide, I ween,

Scarce half the charger’s neck was seen;

For he was barded from counter to tail,

And the rider was armed complete in mail;

Never heavier man and horse

Stemm’d a midnight torrent’s force.

The warrior’s very plume, I say

Was daggled by the dashing spray;

Yet, through good heart, and Our Ladye’s grace,

At length he gain’d the landing place.

What would have become of ourselves if we had attempted to cross the treacherous stream in the dark of the previous night we did not know, but we were sure we should have risked our lives had we made the attempt.

We were only able to explore the churchyard at Lilliesleaf, as the church was not open at that early hour in the morning. We copied a curious inscription from one of the old stones there:

Near this stone we lifeless lie

No more the things of earth to spy,

But we shall leave this dusty bed

When Christ appears to judge the dead.

For He shall come in glory great

And in the air shall have His seat

And call all men before His throne.

Rewarding all as they have done.

We were served with a prodigious breakfast at the inn to match, as we supposed, the big appetites prevailing in the North, and then we resumed our walk towards Hawick, meeting on our way the children coming to the school at Lilliesleaf, some indeed quite a long way from their destination. In about four miles we reached Hassendean and the River Teviot, for we were now in Teviot Dale, along which we were to walk, following the river nearly to its source in the hills above. The old kirk of Hassendean had been dismantled in 1693, but its burial-ground continued to be used until 1795, when an ice-flood swept away all vestiges both of the old kirk and the churchyard. It was of this disaster that Leyden, the poet and orientalist, who was born in 1775 at the pretty village of Denholm close by, wrote the following lines:

By fancy wrapt, where tombs are crusted grey,

I seem by moon-illumined graves to stray,

Where now a mouldering pile is faintly seen—

The old deserted church of Hassendean,

Where slept my fathers in their natal clay

Till Teviot waters rolled their bones away.

Leyden was a great friend of Sir Walter Scott, whom he helped to gather materials for his “Border Minstrelsie,” and was referred to in his novel of St. Ronan’s Well as “a lamp too early quenched.” In 1811 he went to India with Lord Minto, who was at that time Governor-General, as his interpreter, for Leyden was a great linguist. He died of fever caused by looking through some old infected manuscripts at Batavia on the coast of Java. Sir Walter had written a long letter to him which was returned owing to his death. He also referred to him in his Lord of the Isles:

His bright and brief career is o’er,

And mute his tuneful strains;

Quench’d is his lamp of varied lore,

That loved the light of song to pour;

A distant and a deadly shore

Has Leyden’s cold remains.

The Minto estate adjoined Hassenden, and the country around it was very beautiful, embracing the Minto Hills or Crags, Minto House, and a castle rejoicing, as we thought, in the queer name of “Fatlips.”

The walk to the top of Minto Crags was very pleasant, but in olden times no stranger dared venture there, as the Outlaw Brownhills was in possession, and had hewn himself out of the rock an almost inaccessible platform on one of the crags still known as “Brownhills’ Bed” from which he could see all the roads below. Woe betide the unsuspecting traveller who happened to fall into his hands!

But we must not forget Deloraine, for after receiving instructions from the “Ladye of Branksome”—

Soon in the saddle sate he fast,

And soon the steep descent he past,

Soon cross’d the sounding barbican.

And soon the Teviot side he won.

Eastward the wooded path he rode.

Green hazels o’er his basnet nod;

He passed the Peel of Goldieland,

And crossed old Borthwick’s roaring strand;

Dimly he view’d the Moat-hill’s mound.

Where Druid shades still flitted round;